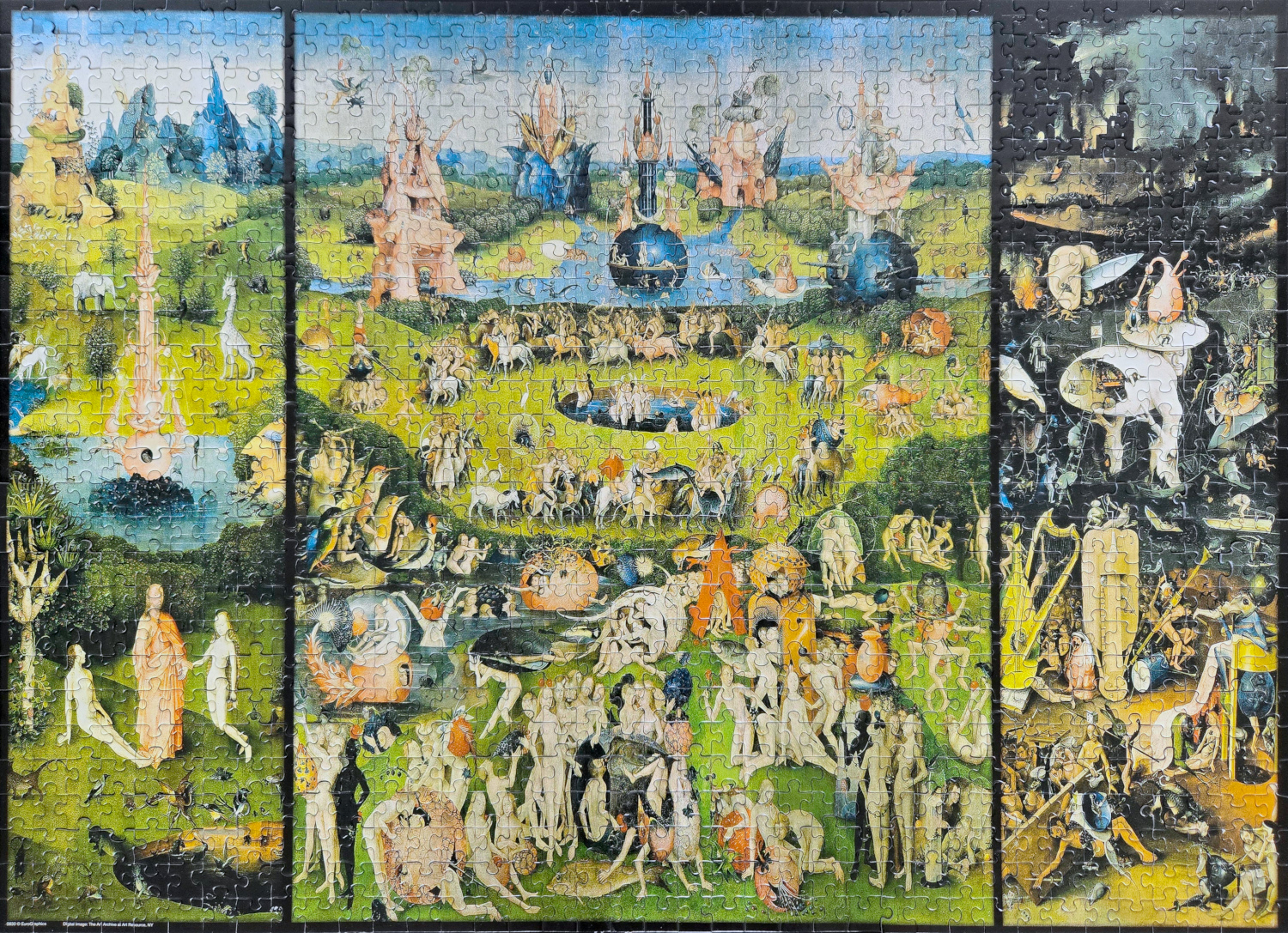

You’ve probably seen it on a tote bag or a Dr. Martens boot. Maybe you saw it in the background of a movie. It’s that massive, trippy triptych where people are riding giant ducks and getting stuffed into bagpipes. Honestly, Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights is the most famous thing most people can’t actually explain. We look at it and see a proto-surrealist fever dream, something Salvador Dalí might have painted if he’d been born in 1450. But Bosch wasn't a surrealist. He wasn't on drugs. He was a deeply conservative, arguably terrified, Catholic man living in a world he thought was going straight to hell. Literally.

It's weird.

The painting sits in the Prado Museum in Madrid today, usually surrounded by a crowd of confused tourists trying to figure out why a bird-headed monster is eating a man and then pooping him out into a pit of despair. To understand the Garden of Earthly Delights, you have to stop looking at it as "art" in the modern sense and start looking at it as a map. It’s a visual sermon. It’s a warning.

The Structure of a Nightmare

Most people only know the middle panel—the one with the naked people and the giant strawberries. But the work is a triptych, meaning it has three panels (plus the shutters when it’s closed).

When you close the wings, you see the world's creation. It’s a grey, watery globe. God is a tiny figure in the corner. It's quiet. Then, you open it up, and the color hits you like a brick. On the left, you have Eden. This isn't the peaceful Eden you're used to. Sure, Jesus (represented as the Word) is there with Adam and Eve, but look in the background. Animals are eating each other. A cat walks off with a mouse. A strange, three-headed bird lurks by a pond. Bosch is telling us that even at the start, something was "off." Nature was already hungry.

Then there's the center. This is the Garden of Earthly Delights itself.

📖 Related: Ashley Johnson: The Last of Us Voice Actress Who Changed Everything

It’s a massive party. Everyone is naked. They’re eating giant fruit, which back then was a shorthand for sexual indulgence because fruit rots quickly. It’s fleeting. It’s sweet, then it’s garbage. You see people inside glass bubbles or hiding under huge shells. There’s a weird lack of genuine connection, though. Everyone is doing their own thing, obsessed with their own pleasure. It’s a chaotic, busy, and ultimately hollow landscape. Art historians like Hans Belting have argued this middle panel might represent a "false paradise"—the world as it would have looked if the Fall had never happened, or perhaps just a snapshot of humanity's collective distraction.

The Right Panel: The Music Lesson from Hell

Then there’s the right panel. This is the one that sticks with you. It’s night. The sky is black, lit only by the orange glow of burning cities. This is Hell.

Bosch’s Hell isn’t just fire and brimstone. It’s specific. It’s "The Musical Hell." You see a man crucified on a harp. Another is trapped inside a lute. In the 15th century, secular music was often viewed as a gateway to sin—a distraction from the divine. Bosch takes that literally.

And then there's the "Tree-Man." His torso is a cracked eggshell filled with a tavern scene. His legs are rotting tree trunks standing in boats. He looks back over his shoulder with a haunting, human expression. Some think it’s a self-portrait of Bosch. Imagine painting yourself as a hollowed-out wreck in the middle of eternal damnation. That’s some heavy self-reflection.

Why Bosch Still Matters in 2026

We’re obsessed with this painting because it feels modern. It feels like a scroll through a chaotic social media feed where everything is happening at once and nothing makes sense. But for Bosch, it made perfect sense. He belonged to the Illustre Lieve Vrouwe Broederschap (Brotherhood of Our Illustrious Lady). He was part of the elite. He was a man of the establishment.

👉 See also: Archie Bunker's Place Season 1: Why the All in the Family Spin-off Was Weirder Than You Remember

The Garden of Earthly Delights wasn't painted for a church. It was likely commissioned by the House of Nassau for their palace in Brussels. This was a "conversation piece." Imagine being a Duke, standing in front of this with your wealthy friends, pointing at a guy getting bit by a giant fish and laughing about how "the commoners" are going to end up like that if they aren't careful. It was a status symbol that preached morality.

The Mystery of the Pig in a Veil

There’s a detail in the Hell panel that most people miss. A pig wearing a nun’s veil is trying to get a man to sign a legal document. It’s hilarious, but also biting. Bosch was likely criticizing the corruption of the church and the legal system. He wasn't just worried about sex and gluttony; he was worried about the soul of the institution.

Historians like Erwin Panofsky and Wilhelm Fraenger have spent decades debating if Bosch was actually part of a secret heretical sect called the Adamites. Fraenger thought the painting was an altarpiece for a group that believed in returning to the innocence of Adam. Most modern scholars, like Laurinda Dixon, disagree. They see Bosch as a straight-edged moralist using the language of alchemy and folk proverbs to scare people into being "good."

Specific Details You Should Look For

If you ever get to stand in front of the real thing, or even if you're just zooming in on a high-res scan, check these out:

- The Strawberry: It’s everywhere. In the Middle Ages, the strawberry was a symbol for the fleeting nature of pleasure. It tastes good for a second, then it’s gone.

- The Glass Tube: In the center panel, a couple is trapped in a glass cylinder. This is an alchemical symbol for a "conjunction," but here it feels claustrophobic.

- The Bird-Monster: In Hell, the "Prince of Hell" sits on a high chair (a close-stool) eating people. He’s blue. He wears a cauldron on his head. He represents the ultimate end of gluttony: you become what you eat, and then you're discarded.

- The Ears: There’s a giant pair of ears holding a knife in the Hell panel. It’s a literal representation of "ears that do not hear" the word of God.

Moving Past the "Weirdness"

It’s easy to call Bosch "weird" and move on. But that’s a cop-out. The Garden of Earthly Delights is a masterpiece of composition. Look at how the horizons of the three panels line up perfectly. Look at the use of pinks and blues that transition into the absolute dark of the final act.

✨ Don't miss: Anne Hathaway in The Dark Knight Rises: What Most People Get Wrong

Bosch was a technical wizard. He used "alla prima" techniques—painting wet-on-wet—which was different from the slow, layered approach many of his contemporaries used. This gave his work a certain energy, a frantic quality that matches the subject matter.

Some people think Bosch was a madman. Others think he was a genius. He was probably just a man who looked at the world and saw a lot of people making bad choices. He saw a world obsessed with things that didn't matter—money, sex, food, status—and he wanted to show what he thought the "bill" would look like at the end of the night.

Actionable Insight: How to Actually "See" Bosch

To truly appreciate the Garden of Earthly Delights, you have to stop trying to see the "whole" thing at once. It’s designed to be read like a book, piece by piece.

- Start with the exterior shutters. Look at the world in its "infant" state. It sets the stage for the explosion of color inside.

- Follow the movement. The figures move from left to right, a literal progression from creation to "delight" to destruction.

- Identify the proverbs. Many of the scenes are visual puns based on Dutch proverbs of the time. For example, "to find a bird's nest" was slang for something entirely different back then.

- Use the "Bosch Project" website. The Bosch Research and Conservation Project has ultra-high-resolution images where you can see every single brushstroke and "pentimenti" (changes the artist made while painting).

Don't just look for the monsters. Look for the humans. They all have the same blank, almost bored expressions. That’s the most chilling part. They aren't suffering yet in the middle panel; they're just... wandering. Bosch isn't just showing us Hell; he's asking us if we’re already there and just haven't noticed the fire yet.