You’ve probably seen the scene. Janelle Monáe, playing Mary Jackson, stands in a courtroom with a mix of nerves and pure steel. She's arguing before a judge to let her attend classes at an all-white high school. It’s the emotional peak of Hidden Figures, the 2016 movie that finally gave Mary Winston Jackson her flowers.

But here’s the thing: Hollywood loves a good montage, and sometimes the real grit of history gets sanded down for the sake of a two-hour runtime.

Honestly, the mary winston jackson movie—formally titled Hidden Figures—is one of those rare biographical dramas that actually gets the "vibe" right even when it plays fast and loose with the calendar. Mary wasn't just a sidekick in the story of John Glenn’s orbit. She was a pioneer who quite literally forced the doors of the University of Virginia's transition program to swing open.

The Courtroom Battle and the Real NASA Timeline

If you're looking for the biggest "gotcha" between the film and reality, it’s the timing. In the movie, everything feels like it’s happening in a frantic blur around 1961 and 1962.

In reality? Mary Jackson had already broken the engineering glass ceiling years before John Glenn ever stepped into a capsule.

She became NASA’s (well, then it was NACA) first Black female engineer in 1958. By the time the events of the movie’s climax were unfolding, she had already co-authored her first major research report, Effects of Nose Angle and Mach Number on Transition on Cones at Supersonic Speeds.

The movie makes it look like she was fighting for those classes while the Friendship 7 mission was under pressure. But Mary was a visionary who saw the shift from "human computer" to "engineer" coming a mile away. She didn't wait for a crisis to demand her seat at the table.

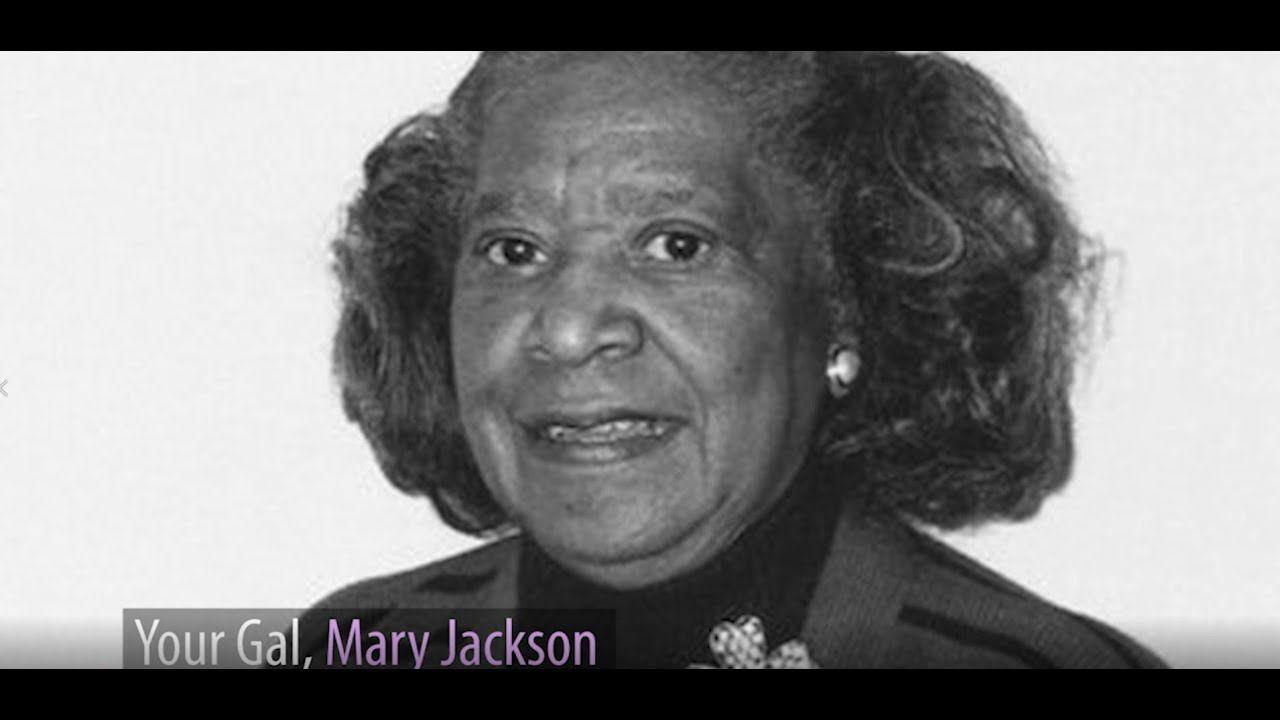

Janelle Monáe as Mary: A Performance That Stuck

Choosing Janelle Monáe was a stroke of genius. Most people knew her as a musician, but she captured Mary’s "feisty" reputation perfectly.

👉 See also: Where Can I Watch the Movie Glory and Why It Still Hits Hard Today

The real Mary Jackson was known around Langley for being outspoken. There’s a story—partially reflected in the film—where she got into a heated argument with an engineer over the segregated bathrooms. Instead of firing her or writing her up, that engineer, Kazimierz Czarnecki, actually listened.

He was the one who suggested she move from the computing pool into the Supersonic Pressure Tunnel. This wasn't some minor lab; it was a 60,000-horsepower wind tunnel that could blast models with winds twice the speed of sound.

The "White Savior" Myth vs. The Bathroom Sign

We have to talk about the bathroom scene. You know the one—Kevin Costner’s character, Al Harrison, grabs a crowbar and smashes the "Colored Ladies" sign.

It’s a great cinematic moment. It’s also total fiction.

- Al Harrison isn't real. He’s a composite character of several NASA directors.

- The sign-smashing never happened. Segregation at Langley was largely phased out in 1958 when NACA became NASA.

- Mary’s frustration was individual. While the movie shows Katherine Johnson (Taraji P. Henson) running half a mile to use the restroom, in real life, Mary Jackson was the one who famously vented her frustration about the "colored" bathrooms to her white colleagues.

She didn't wait for a man with a crowbar. She navigated the system, filed the petitions, and won her legal right to enter the "white" classrooms at Hampton High School on her own merits.

Why Mary Jackson Left Engineering in 1979

This is the part the movie doesn't show because it happens years later. After two decades as a top-tier aerospace engineer, Mary did something that confused a lot of people: she took a demotion.

She saw that Black women and other minorities were hitting a "glass ceiling" in management. She realized she could do more good by leaving the wind tunnels behind and becoming NASA’s Federal Women’s Program Manager.

She spent the rest of her career helping the next generation of women get hired and promoted. She was basically the real-life version of the mentor everyone wishes they had.

Quick Facts: The Real Mary Jackson

- Education: She had a dual degree in Math and Physical Sciences from Hampton Institute (1942).

- Early Career: She wasn't always at NASA; she was a teacher, a bookkeeper, and even a receptionist before she started at Langley in 1951.

- Community: She led a Girl Scout troop for over 30 years and helped kids build their own wind tunnels.

- Legacy: In 2020, NASA officially renamed its Washington, D.C. headquarters the Mary W. Jackson NASA Headquarters.

The Impact of the "Mary Winston Jackson Movie" Today

When Hidden Figures hit theaters, it changed the curriculum in schools across the country. Suddenly, "human computers" weren't a footnote; they were the story.

Mary’s journey—from a math teacher to an engineer to an advocate—is a blueprint for navigating spaces that weren't built for you. The movie might have simplified the math and condensed the years, but it didn't lie about the spirit of the woman.

She really did go to court. She really did sit in a classroom where no one looked like her. And she really did help put humans in space.

If you want to truly honor Mary Jackson's legacy, don't just watch the movie. Look into the Mary Jackson Scholarship or check out the actual research papers she authored for NASA. You can find them in the NASA Technical Reports Server. Reading the complex math behind supersonic flight with her name at the top is way more satisfying than any Hollywood script.

The best way to engage with this history is to look for the names that aren't in the credits. Mary was one of hundreds. Her story is a reminder that being "the first" is a heavy burden, but it’s one she carried so others wouldn't have to.

📖 Related: Why the Coca-Cola Polar Bear Commercial Still Works After 30 Years

Seek out the book by Margot Lee Shetterly for the full, un-Hollywoodized version. It’s dense, it’s technical, and it proves that the truth is often more impressive than the "based on a true story" version.