You know it. I know it. Every kid in the English-speaking world knows the hickory dickory dock rhyme by heart before they can even tie their own shoes. It’s one of those weirdly sticky bits of folklore that just lives in the back of your brain, waiting for a grandfather clock to chime or a mouse to scurry across a floor. But if you actually sit down and look at the words—really look at them—it’s a bit of a head-scratcher. Why a mouse? Why the clock? And what on earth does "hickory dickory" even mean?

Most people assume it’s just nonsense. Just some rhythmic babble to get a toddler to giggle. While there’s some truth to that, the history of these verses is a lot messier and more interesting than your average Mother Goose book lets on. It isn’t just about a rodent’s failed attempt at climbing furniture. It’s actually tied to ancient shepherd counting systems, astronomical tools, and even 18th-century social commentary.

Honestly, the way we teach nursery rhymes today is kinda sanitized. We treat them like little bubbles of innocence, forgetting that back in the day, these were the "viral memes" of the 1700s. They carried history, inside jokes, and sometimes even warnings.

✨ Don't miss: Finding Unique C Names Girl: Why Modern Parents Are Moving Past Catherine and Chloe

The Nonsense That Actually Makes Sense

Let’s talk about those opening words. "Hickory, dickory, dock." It sounds like gibberish, right? Well, linguists and historians who nerd out over British folklore, like the late Iona and Peter Opie (who basically wrote the bible on nursery rhymes, The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes), suggest a different origin.

See, back in the day, shepherds in the North of England used a specific counting system called the "Westmorland Borrowdale" or "Celtic Score." It was used for counting sheep. The numbers sounded like this: Hevera (eight), Devera (nine), Dick (ten). You can hear the echo, can't you? Hickory dickory dock rhyme might just be a corruption of a shepherd trying to keep track of his flock.

- Hevera became Hickory

- Devera became Dickory

- Dick became Dock

It’s a linguistic drift. Over hundreds of years, "eight, nine, ten" turned into a catchy rhythm for children. It’s basically the 18th-century version of a "remix" that went way more popular than the original track.

Why the Mouse?

You might wonder why a mouse is the protagonist here. In the early 1700s, when this rhyme started appearing in print—specifically in Tommy Thumb's Pretty Song Book around 1744—the mouse was a common fixture in every household. No, not as a pet. As a pest. But there's a practical side to this too. Mice are fast. They’re frantic. The image of a mouse sprinting up a clock only to be startled by a loud "BONG" is peak physical comedy for a three-year-old.

But there’s a more technical theory. Some horologists (clock experts) suggest the rhyme refers to the "warning" sound a large clock makes before it strikes the hour. That internal mechanical "click" can sound like a small animal moving inside the wooden casing. When the clock actually strikes one, the weight drops, the bell rings, and the "mouse" (the sound) vanishes.

Variations You’ve Probably Never Heard

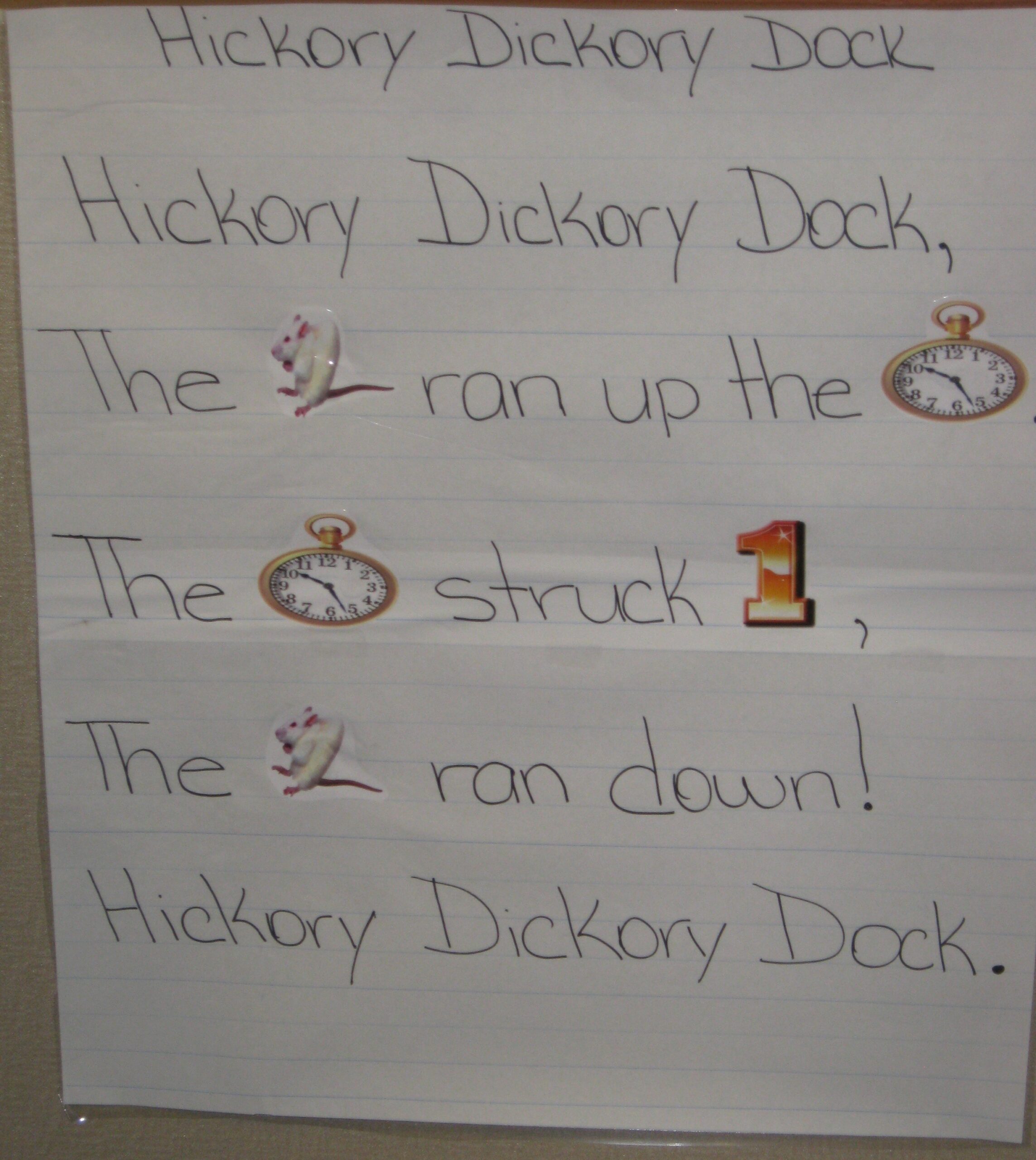

The version we sing today is usually just one verse. The mouse goes up, the clock strikes one, the mouse goes down. Done. But older versions were much longer and, frankly, a bit more chaotic.

✨ Don't miss: Why Pinoy Tambayan at Lambingan Culture Is Actually the Secret to Filipino Resilience

In some 19th-century collections, the rhyme continues through the hours of the day. For example:

- The clock struck two, the mouse said "BOO!"

- The clock struck three, the mouse went "WEE!"

- The clock struck four, he fell on the floor.

It’s essentially an early form of a counting game. Teachers and parents used the hickory dickory dock rhyme to teach the concept of time. Before digital watches, understanding a striking clock was a vital life skill. If you couldn't count the bells, you didn't know when to eat or when to work. This rhyme was the "educational app" of the 1700s.

The Connection to Astronomical Clocks

If you want to get really deep into the weeds, some folks point toward the astronomical clock at Exeter Cathedral. This thing is a marvel. It’s been there since the 15th century. Underneath the main dial, there’s actually a small hole in the door. Why? For the cat.

Records show that the cathedral used to pay a weekly allowance for a "cat in the clock" to keep the mice away from the grease-coated ropes and leather parts of the mechanism. If a mouse climbed that clock, it wasn't just a cute story; it was a threat to the machinery. The hickory dickory dock rhyme might be a folk-memory of the constant battle between rodents and the delicate gears of ancient timekeepers.

Why We Still Care in 2026

It’s fascinating that in a world of AI and instant streaming, we still sit on the edge of a bed and recite a poem about a mouse from the 1740s. Why?

Rhythm.

Human brains are hardwired for cadence. The "dactylic" meter of the rhyme (one stressed syllable followed by two unstressed) mimics the actual ticking of a pendulum. TICK-et-y, TICK-et-y, TICK. It’s a literal sonic representation of time passing. It’s soothing. It’s predictable.

💡 You might also like: Why Words That Start With An E Are Harder Than You Think

Also, it’s one of the few nursery rhymes that hasn't been "canceled" or found to have a super dark, plague-related origin (looking at you, Ring Around the Rosie). It’s just... a mouse and a clock. It’s safe. It’s a rare piece of folklore that is exactly what it looks like on the surface, even if the roots go back to shepherds in the hills of Cumbria.

Common Misconceptions About the Rhyme

People love to invent deep, dark meanings for these things. You’ll find Reddit threads claiming the mouse represents a specific king or a failed political coup. Honestly? There’s no evidence for that. Unlike Humpty Dumpty, which many historians link to a specific cannon during the English Civil War, the hickory dickory dock rhyme doesn't have a smoking gun.

It’s also not "Hickory Dickory Doc" as in a doctor. I’ve seen people try to link it to 18th-century physicians. Nope. It’s "Dock." As in "to cut short" or just a phonetic placeholder for the "Dick" in the Celtic counting system. Don't overthink the medical angle. It’s not there.

How to Use This Rhyme Today (Actionable Stuff)

If you’re a parent, teacher, or just someone who likes history, don’t just sing it. Use it.

- Teach Numbers Through Sound: Use the old shepherd's counting system (Hevera, Devera, Dick) to show how languages evolve. It’s a great way to explain that English wasn't always the way it is now.

- Physical Play: The rhyme is a perfect "climax" game. Fingers "running" up a child’s arm (the mouse) and then "running" back down when the clock strikes (a gentle tickle or clap). This builds "anticipatory response" in developing brains.

- Explore Horology: Use the rhyme as a jumping-off point to look at how old clocks actually work. Show a kid a pendulum. Explain how gravity and gears work together. It turns a 10-second poem into a physics lesson.

- Compare Versions: Look up the 1744 version vs. the 1850 version vs. the modern version. It’s a masterclass in how oral tradition changes based on what people find funny or useful.

Ultimately, the hickory dickory dock rhyme survives because it works. It’s a perfect loop of sound and imagery. It’s a tiny piece of the 18th century that we carry around in our pockets, completely free of charge. Next time you hear a clock strike, just remember—somewhere, in the history of the English language, there’s a shepherd counting his sheep and a mouse trying to stay away from a cathedral cat.

To dig deeper into the actual linguistics of these rhymes, check out the archives at the British Library or the Folklore Society. They have the original manuscripts from the 1700s that show just how much these lyrics have shifted over the centuries. You can also visit the Exeter Cathedral to see the famous "cat hole" in the clock door for yourself. It’s a tangible link to a rhyme that most people think is just a fairy tale.