John McNaughton didn't just make a movie in 1986. He made a problem. Most horror films give you a way out—a final girl, a masked killer who feels like a cartoon, or some supernatural logic that lets you sleep at night. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer doesn't care about your comfort. It’s a bleak, low-budget gut punch that feels less like a Friday night feature and more like a crime scene video you weren't supposed to find. It’s dirty. It’s grainy. Honestly, it’s still one of the most upsetting things ever put to celluloid.

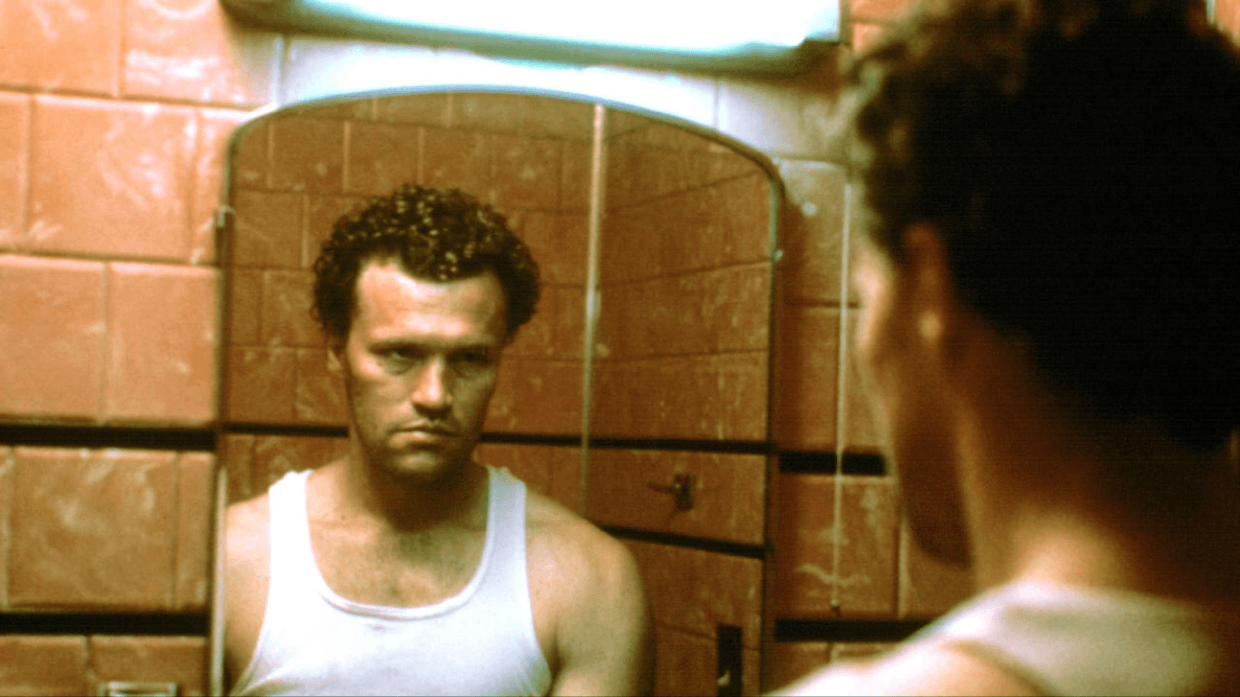

The film stars Michael Rooker in his debut role. Before he was blue-skinned in Guardians of the Galaxy or a fan favorite in The Walking Dead, he was Henry. He wasn't playing a "movie" killer. He was playing a void. The character is loosely, and I mean loosely, based on the real-life confessions of Henry Lee Lucas. If you look at the history of 80s cinema, everything was neon and synth-pop, but Henry was a gray, windowless room in Chicago.

Why Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer Was Banned and Boxed

The MPAA absolutely hated this movie. Not just for the gore—though there is plenty—but for the "moral tone." That’s code for the fact that the movie refuses to punish its protagonist. In the mid-80s, the ratings board basically told McNaughton that no amount of cutting would get the film an R rating. It was handed an X, which back then was the kiss of death usually reserved for pornography. Because of that, the film sat on a shelf for years. People only knew about it through whispers at film festivals or bootleg tapes.

It didn't get a proper release until 1990. By then, it had built up this mythic status. It wasn't just a movie anymore; it was a forbidden object.

The story follows Henry and his roommate Otis, played by Tom Towles. Otis is a creep, a low-level predator who lacks Henry’s cold, calculated discipline. When Otis’s sister Becky (Tracy Arnold) moves in to escape an abusive marriage, the dynamic shifts into something deeply uncomfortable. You almost want to root for Becky. You want her to fix Henry. But the movie mocks that impulse. It shows you that Henry isn't a "broken man" you can save; he’s a shark that just happens to look like a guy in a flannel shirt.

The Home Invasion Scene That Changed Horror

We have to talk about "the scene." You know the one if you’ve seen it. If you haven't, it’s the moment the film transitions from a character study into something genuinely transgressive. Henry and Otis record themselves murdering a family using a stolen video camera.

💡 You might also like: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

The brilliance—and the horror—of this sequence is the perspective. We aren't watching the murder directly. We are watching a television screen playing back the murder while Henry and Otis watch it on their couch, drinking beer. It’s meta-commentary before that was a buzzword. It forces the audience to realize they are also voyeurs. We are sitting in the dark watching the same thing the killers are watching. It’s a hideous, masterfully executed moment that makes you want to take a shower.

McNaughton used a 16mm camera to give the film that documentary feel. It looks cheap because it was cheap. They shot it in less than a month for about $110,000. But that lack of polish is exactly why it works. It doesn't feel like "art." It feels like evidence.

Real Life vs. The Film: The Henry Lee Lucas Connection

People often mistake this for a documentary. It’s not. While the names Henry and Otis (referring to Otis Toole) are real, the events are highly fictionalized. The real Henry Lee Lucas was a pathological liar. He confessed to hundreds of murders across the United States, most of which he couldn't possibly have committed.

The Texas Rangers and other law enforcement agencies eventually realized Lucas was playing them. He liked the attention. He liked the grilled cheese sandwiches and the milkshakes the investigators gave him during interviews. In reality, Lucas was likely responsible for about a dozen killings, which is horrific enough, but he wasn't the nomadic super-predator the film portrays.

The movie takes the myth of Henry Lee Lucas and uses it to explore the banality of evil. In the film, Henry tells Becky about how he killed his mother. It’s a haunting monologue. Rooker delivers it with this flat, terrifying detachment. In real life, Lucas did kill his mother, but the circumstances were a mess of domestic violence and drunken rage, not the cold execution Rooker describes.

📖 Related: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

The Problem With Otis

Tom Towles’s portrayal of Otis is arguably more disturbing than Henry. Henry has a code—sort of. He changes his methods so he doesn't get caught. He doesn't use the same weapon twice. He’s a professional. Otis, however, is a chaotic, impulsive animal.

The relationship between the two men is the core of the film’s darkness. It’s a mentorship in murder. Henry "teaches" Otis how to kill like a bored older brother teaching a sibling how to fix a car. There is no joy in it for Henry, only a grim necessity. Watching Otis lean into the violence with a sick, perverse glee creates a contrast that makes Henry’s coldness even more chilling. It’s a "good cop/bad cop" dynamic where both cops are actually demons.

Why We Still Talk About This Movie in 2026

Modern true crime is everywhere. We have glossed-up Netflix series starring heartthrobs as Ted Bundy or Jeffrey Dahmer. Those shows often accidentally romanticize the killers. They make them seem brilliant, misunderstood, or tragic.

Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer does the opposite.

It strips away the glamour. There is no cool soundtrack. There are no dramatic courtroom speeches. There is just a guy who kills people and then goes to get a sandwich. It’s the "ordinariness" that sticks with you. You could pass Henry on the street and never know. He’s the guy at the gas station. He’s the guy sitting behind you on the bus.

👉 See also: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

Critics like Roger Ebert famously championed the film, giving it a rare four-star review and fighting against the MPAA’s censorship. Ebert recognized that the film wasn't exploitative in the traditional sense; it was a serious piece of art that refused to blink. It forced society to look at violence without the safety net of "entertainment" tropes.

Actionable Insights for Horror Fans and Filmmakers

If you are a student of cinema or a fan of the genre, there are specific things to take away from this film's legacy. It’s more than just a "scary movie."

- Study the Power of Restraint: Notice how McNaughton doesn't use jump scares. The horror comes from the frame staying still while something terrible happens.

- Audio Matters: The score for Henry is a low, industrial drone. It’s oppressive. If you’re making film, realize that what the audience hears is often more frightening than what they see.

- The Ethics of True Crime: Use this film as a lens to critique modern media. Does a piece of media humanize the victim, or does it turn the killer into a celebrity? Henry manages to avoid the "celebrity" trap by making Henry pathetic and empty.

- Check the 30th Anniversary Restoration: If you’ve only seen grainy YouTube clips, find the 4K restoration. It preserves the 16mm grit but allows you to see the incredible nuance in Michael Rooker’s performance.

Watching this film isn't a fun experience. It’s a heavy one. But in a world where horror is often sanitized for mass consumption, Henry remains a vital, jagged reminder of what the genre is capable of when it stops trying to be liked. It is a portrait of a man, a city, and a darkness that doesn't have a punchline.

To truly understand the evolution of the slasher and the psychological thriller, you have to sit with Henry. You have to endure the silence of that final shot. It’s not just a movie; it’s a landmark of independent cinema that proved you don’t need a big budget to leave a permanent scar on the culture.

Next Steps for the Curious:

- Compare the film's narrative to the 2003 book Henry Lee Lucas: The Shocking True Story of America's Most Notorious Serial Killer by Joel Norris to see how the "confession craze" influenced pop culture.

- Watch Michael Rooker's early interviews regarding the role; he stayed in character for much of the shoot, which deeply unsettled the crew.

- Explore the "Chicago School" of filmmaking that emerged in the 80s, prioritizing grit and realism over Hollywood gloss.