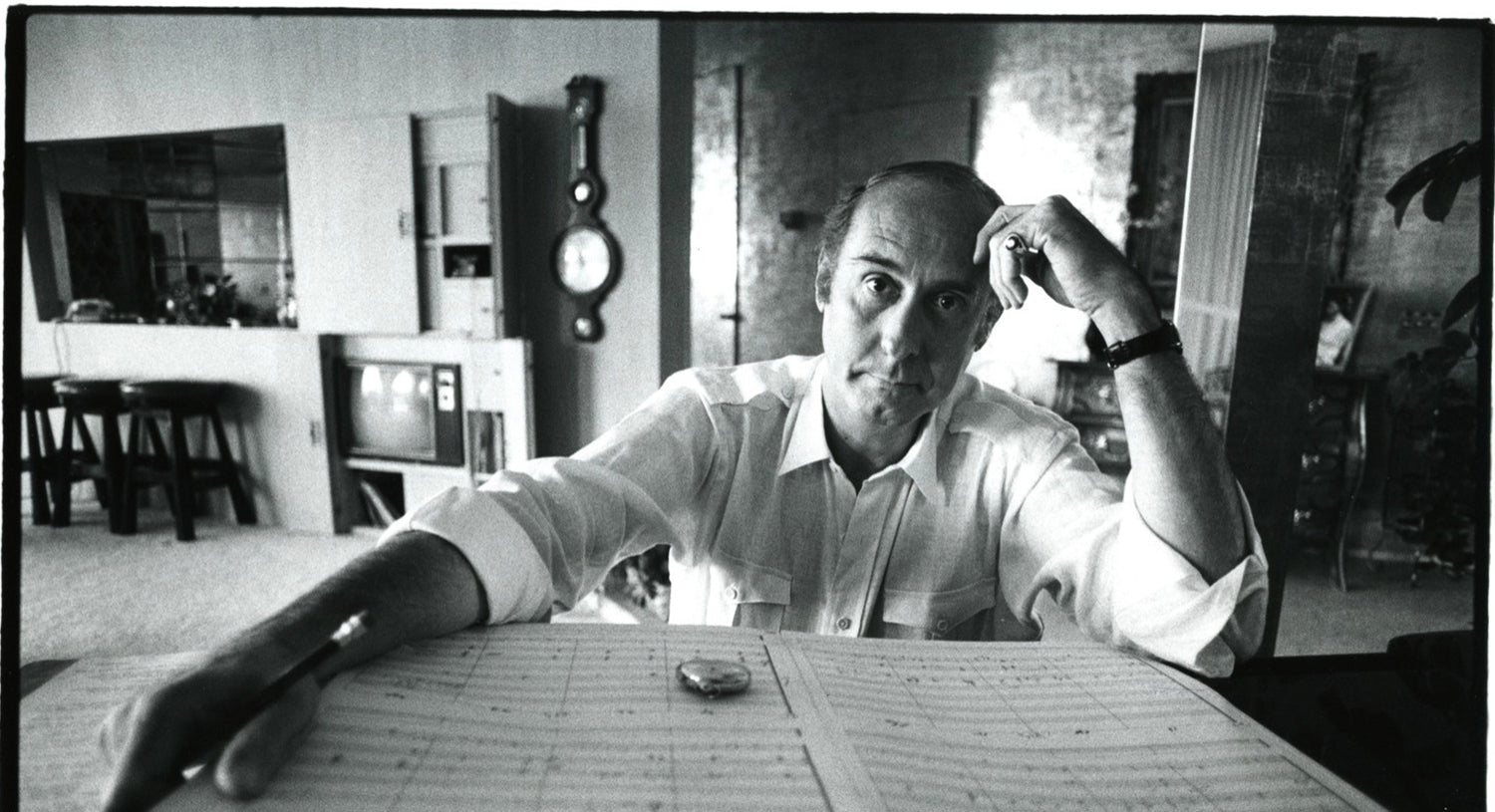

You know that smooth, slinky saxophone riff from The Pink Panther? Or that wistful, tear-jerking melody of "Moon River"? That’s Henry Mancini. But while Hollywood claims him as their golden boy, folks in Western Pennsylvania know the truth. Before the 20 Grammys and the four Oscars, he was just Enrico, a kid from a gritty steel town playing the flute with his dad.

The Henry Mancini Pennsylvania Music Hall of Fame connection isn't just about a trophy on a shelf. It’s about a guy who never forgot that his "Moon River" was actually inspired by the way the light hit the Ohio River back home.

The Steel Town Roots of a Musical Giant

Henry Mancini wasn't born into glitz. He was born in Cleveland in 1924, but his soul was forged in West Aliquippa, Pennsylvania. Honestly, if you talk to his daughter Monica, she’ll tell you he was very specific about that "West" part. It was a tough, immigrant-heavy mill town. His dad, Quinto, was a steelworker who spent his days in the heat of the Jones & Laughlin Steel Company and his nights playing the piccolo.

He forced Henry to start flute at age eight. Most kids would’ve bailed, but Henry leaned in. By 12, he was tackling the piano.

Think about that for a second. While other kids were probably dreaming of escaping the mills through sports or labor, Henry was busy studying with Max Adkins, the conductor at the Stanley Theatre in Pittsburgh. Adkins was the real deal. He taught Henry that music wasn't just about playing notes; it was about the arrangement. That "Pittsburgh sound"—a mix of jazz, big band, and classical—became the blueprint for every iconic film score he’d ever write.

👉 See also: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

Why the Pennsylvania Music Hall of Fame Matters

When we talk about the Pennsylvania Music Hall of Fame, we’re looking at a legacy that bridges the gap between the local VFW hall and the Academy Awards. Mancini’s induction—and his place in the broader Beaver Valley Musicians Hall of Fame—isn't just a formality. It’s a recognition of the "Aliquippa kid" who made it.

Pennsylvania has a weirdly high concentration of musical geniuses, but Mancini is the one who defined the sound of the 20th century.

- He transformed television music with Peter Gunn.

- He made jazz "cool" for suburban parents.

- He proved that a kid from a mill town could go to Juilliard and then conquer the world.

There’s a reason the Lincoln Park Performing Arts Center in Midland, PA, hosts the Henry Mancini Awards. It’s about keeping that pipeline open. They recognize high school musical theater talent in Beaver, Butler, Lawrence, and Mercer counties. It’s basically the local Tonys, and it’s a direct nod to the fact that Mancini’s journey started in a Pennsylvania classroom.

The "Moon River" Mystery: Pennsylvania or Hollywood?

There’s this long-standing theory among Beaver County locals. They say the inspiration for "Moon River" wasn’t some fancy creek in the South or a dream of New York. They believe it was the Ohio River.

✨ Don't miss: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

The story goes that young Henry used to sit outside his house in West Aliquippa at night. He’d watch the moon reflect off the water, the way the light shimmered against the industrial backdrop. Whether or not that’s 100% true doesn't really matter. What matters is that the emotional weight of his music—that sense of longing and "huckleberry friends"—feels deeply rooted in the working-class sentiment of the region.

A Career That Broke All the Rules

Mancini’s career was basically one long "first."

- He won the very first Grammy for Album of the Year in 1959 for The Music from Peter Gunn.

- He bridged the gap between the Glenn Miller big-band era and the rock-and-roll 60s.

- He stayed married to the same woman, Ginny O'Connor (a singer for the Glenn Miller-Tex Beneke Orchestra), for 47 years—a total anomaly in Hollywood.

He wasn't a diva. He was a worker. That’s the Pennsylvania in him. Even when he was scoring Breakfast at Tiffany’s or The Days of Wine and Roses, he approached it with a blue-collar discipline. He wrote over 90 albums. He conducted over 600 symphony performances. The guy just didn't stop.

The 100th Birthday Celebration

In 2024, the world celebrated the Mancini Centennial. The Library of Congress opened up his archives—we’re talking 900 boxes of manuscripts. But while D.C. has the papers, Pennsylvania has the spirit. The Henry Mancini Pennsylvania Music Hall of Fame legacy lives on through the Henry Mancini Arts Academy. It’s not just about the past; it’s about the kids in Beaver County today who are picking up a flute because they heard their great-grandpa talk about the guy who wrote the Pink Panther theme.

🔗 Read more: Wrong Address: Why This Nigerian Drama Is Still Sparking Conversations

What Most People Get Wrong About Mancini

Most people think he was just a "film guy."

Actually, Mancini was a pioneer of the "easy listening" genre, but don't let that term fool you. His arrangements were incredibly complex. He used unusual instruments—like the bass flute in Peter Gunn—to create moods that nobody had ever heard on TV before. He was an innovator disguised as a pop star.

And he was humble. He famously said he was "a lucky guy" who happened to meet the right people at the right time. But you don't get 72 Grammy nominations by being "lucky." You get them by having the kind of work ethic that's bred in a steel town where you either work hard or you don't eat.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Musicians

If you’re a fan of Mancini or a musician looking to follow in his footsteps, here is how you can actually engage with his Pennsylvania legacy:

- Visit the Lincoln Park Performing Arts Center: Check out the Henry Mancini Arts Academy in Midland, PA. It’s the heart of his educational legacy.

- Listen Beyond the Hits: Grab the soundtrack to Touch of Evil (1958). It’s dark, gritty, and shows his range far beyond the "light" music he's often pigeonholed into.

- Support Local Music Halls of Fame: These organizations often operate on shoestring budgets. Whether it's the Pennsylvania Music Hall of Fame or your local Beaver Valley chapter, they are the ones preserving the stories of the artists who came before us.

- Study the Arrangements: If you're a composer, look at his book Sounds and Scores. It’s still one of the best resources for understanding how to make an orchestra sound modern.

Henry Mancini might have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, but his foundation was built on the riverbanks of Pennsylvania. He proved that you can take the boy out of the mill town, but the rhythm of the mill—the steady, driving beat of hard work—never leaves the music.

To truly honor Mancini's legacy, start by exploring his lesser-known scores like The Party or Experiment in Terror. Then, look into the current recipients of the Henry Mancini Awards in Western Pennsylvania; supporting the next generation of performers is the most direct way to keep his "Moon River" flowing.