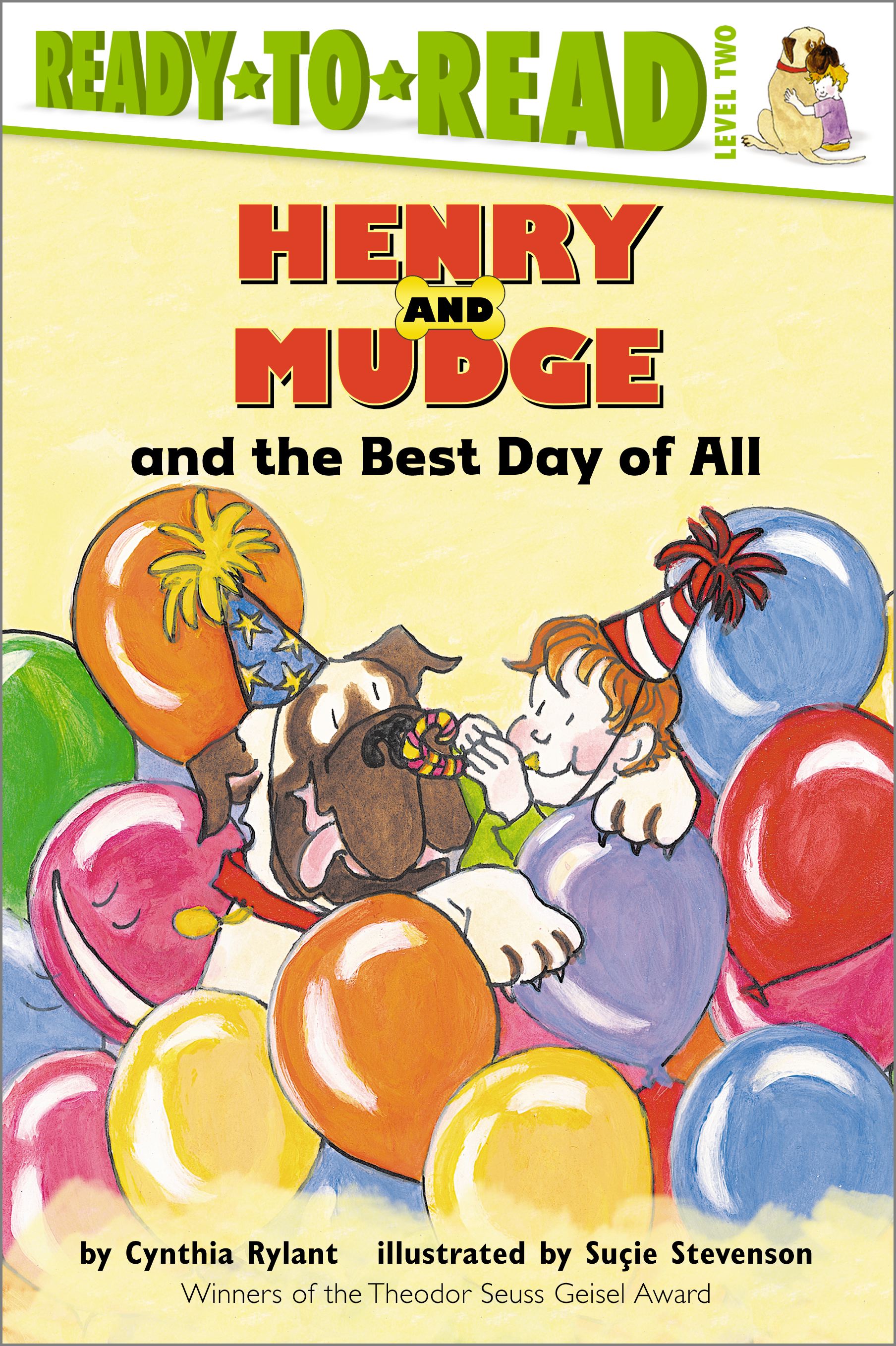

You probably remember the cover art. A small boy with a cowlick and a dog so massive he looks like a toasted marshmallow with legs. That’s Mudge. He’s an English Mastiff, and honestly, he’s the heart of the whole series. Cynthia Rylant started this journey back in 1987, and if you look at any first-grade classroom today, these books are still there. They’re battered. They have taped spines. They’ve been sneezed on by seven-year-olds for decades.

Why?

Because Henry and Mudge books don’t try too hard. They aren’t "educational" in that annoying, preachy way that makes kids want to close the book and go play Minecraft. They’re just... quiet. They deal with things like being lonely, getting a cold, or worrying about a loose tooth. It’s the "Seinfeld" of children’s literature—a show about nothing, which is actually about everything when you're six years old.

The Genius of Cynthia Rylant’s Structure

Rylant is a heavy hitter in the world of kid-lit. She’s won the Newbery Medal (for Missing May), but the Henry and Mudge series is where she mastered the "Ready-to-Read" format. Most people don't realize how hard it is to write a book using only a few hundred unique words without sounding like a robot.

Most "easy readers" are boring. "See the dog. The dog is big."

Rylant doesn't do that. She uses rhythm.

"Henry had no brothers and no sisters. 'I want a brother,' he said to his parents. 'Sorry,' they said."

That’s the opening of the very first book. It’s punchy. It’s real. It acknowledges that kids have desires that parents sometimes just can't fulfill. Then comes Mudge. He wasn’t always 180 pounds. He started as a puppy that fit in a shoe box. But then he grew. And grew. He grew out of seven collars in a row.

📖 Related: What Does a Stoner Mean? Why the Answer Is Changing in 2026

This specific detail—the seven collars—is the kind of thing kids obsess over. It's a concrete fact. It makes the world of Henry and Mudge feel grounded in reality, even if the dog is large enough to be a small pony.

Why the Henry and Mudge Books Work for "Struggling" Readers

We use the term "struggling readers" a lot, but usually, it just means kids who are bored or intimidated. The Henry and Mudge books are categorized as Level 2 readers. This is the "sweet spot" of literacy development.

The sentences are short, but they aren't choppy. Suçie Stevenson’s illustrations do a lot of the heavy lifting here. If a child doesn't recognize the word "crackers," they can see the box of saltines on the table in the drawing. This isn't cheating; it's "contextual cuing." It builds confidence.

The Emotional Stakes

Take Henry and Mudge and the Bedtime Thumps. It’s literally about being scared of noises at night in a strange house.

A lot of modern children's books try to be high-concept. They involve magic portals or talking toasters. Henry and Mudge stays in the backyard. It stays in the living room. It deals with the anxiety of a big dog being scared of a small cat. By keeping the stakes relatable, Rylant allows the child to focus on the decoding of the words rather than trying to follow a complex plot.

The Order Matters (Sort Of)

There are 28 books in the original series. You don't necessarily have to read them in order, but the first one, simply titled Henry and Mudge, is essential. It establishes the "why."

Henry was lonely. Now he isn't.

👉 See also: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

From there, the series branches out into seasonal themes. You’ve got Henry and Mudge in Puddle Trouble (spring), Henry and Mudge and the Starry Night (summer), and Henry and Mudge under the Yellow Moon (fall). This is a classic publishing tactic, but it works because it teaches kids how to categorize their own lives through the seasons.

If you’re looking to build a collection, don’t feel pressured to buy the "Collector’s Set" immediately. Honestly, these are best found in the used bin of a local bookstore. The older, yellowed copies feel more authentic. There’s something about a 1990s paperback edition of Henry and Mudge and the Long Weekend that just hits different.

Addressing the "Boring" Allegations

Some parents find these books tedious. I get it. If you’re used to reading Harry Potter or even The Bad Guys, the adventures of a boy and his dog might seem a bit thin.

But you aren't the audience.

To a kid who just figured out how to sound out the "dg" in "Mudge," these books are a marathon. They are a triumph. When a child finishes a 40-page book by themselves for the first time, it changes their brain chemistry. They stop seeing books as "work" and start seeing them as trophies.

Key Themes You Might Have Missed

It isn't just about a dog. It’s about a very specific type of childhood. Henry’s parents are actually present. In a lot of children's fiction, the parents are either dead (thanks, Disney) or completely incompetent. Henry's parents are chill. They go camping. They make popcorn. They let the 180-pound dog sleep on the bed.

This creates a sense of "psychological safety."

✨ Don't miss: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

- Self-Reliance: Henry often solves his own small problems, like finding a way to entertain himself on a rainy day.

- Empathy: Henry has to care for Mudge. He has to think about what the dog needs.

- The Beauty of Ordinary Life: There is no "villain" in Henry and Mudge. The "antagonist" is usually a rainy day, a bad cold, or a grumpy cousin named Annie.

Speaking of Annie—she eventually got her own spin-off series (Annie and Snowball). It’s fine, but it lacks the weight (literally) of Mudge.

How to Use These Books for Literacy Growth

If you have a kid who is stuck on picture books and scared of "chapter books," Henry and Mudge books are your bridge. They look like chapter books. They have "chapters" (usually three per book). But the text density is low.

Try the "You Read, I Read" method.

You read a page, the kid reads a page. Because the vocabulary is repetitive, the words you read on page 4 will likely show up again for the kid on page 5. This is called "priming." It makes them look like a genius, and they'll love the feeling of "knowing" a word before they even consciously process it.

The Legacy of the 180-Pound Mastiff

Cynthia Rylant has mentioned in interviews that Mudge was inspired by her own large dog. That’s probably why the behavior feels so real. Mudge drools. He sheds. He gets "the thumps" when he wags his tail against the floor.

It's those tiny, messy details that keep the series from feeling like a sterile "educational tool."

The series technically ended its original run years ago, but the "Ready-to-Read" brand keeps re-releasing them with fresh covers. Don't be fooled—the insides are the same. Whether it's the 1987 version or the 2024 reprint, the story of a lonely boy finding a massive, smelly, loving friend is universal.

Actionable Steps for Parents and Teachers:

- Start with the "Green" level: Look for the Level 2 "Ready-to-Read" badge on the top right corner.

- Focus on the Seasons: If it’s October, grab Henry and Mudge under the Yellow Moon. Linking the book to the child's current environment doubles the engagement.

- Don't Correct Every Mistake: If they say "house" instead of "home," let it go. Fluency is about the flow. If the meaning is the same, keep moving.

- Visit the Library: Most libraries have the entire 28-book run. Let the child pick based on the cover art. Ownership over the choice is half the battle in reading.

- Observe the Art: Ask the child what Mudge is feeling in the drawings. It’s a great way to build emotional intelligence alongside literacy.

The world of Henry and Mudge is a small one, but it's built to last. It’s a reminder that stories don't need to be loud to be important. Sometimes, they just need to be about a boy, a dog, and a very large box of crackers.