You’ve probably seen that grid taped to a doctor's office wall or printed on the back of a generic health pamphlet. It's the height weight body mass index chart, a colorful mosaic of green, yellow, and red squares meant to tell you exactly where you stand in the eyes of medical science. But honestly, it’s a bit of a blunt instrument. Developed nearly 200 years ago by a Belgian mathematician named Adolphe Quetelet—who, for the record, wasn't even a doctor—the BMI was never actually intended to diagnose individual health.

It was a tool for social statistics.

Yet, here we are in 2026, still using this math to determine insurance premiums, surgery eligibility, and how we feel about our own bodies. It's weird. We're obsessed with a number that doesn't know the difference between five pounds of bicep and five pounds of visceral fat. If you've ever felt like your "overweight" classification didn't match the person looking back in the mirror, you're definitely not alone.

How the Height Weight Body Mass Index Chart Actually Works (The Math Bit)

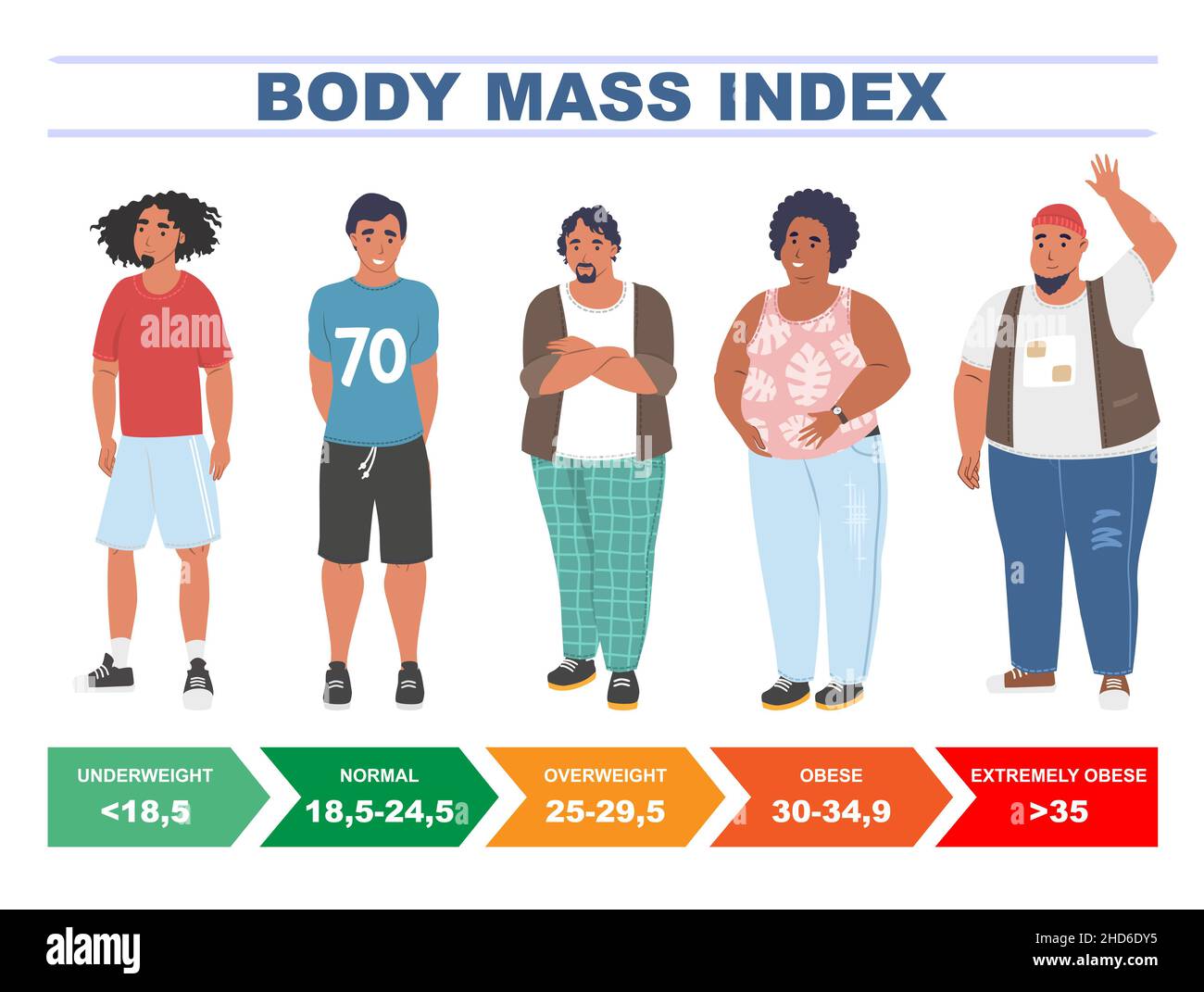

The calculation is surprisingly simple. You take your weight in kilograms and divide it by the square of your height in meters. In the U.S., we usually multiply that by 703 because we're still clinging to pounds and inches. The resulting number slots you into a category. Under 18.5 is underweight. Between 18.5 and 24.9 is "normal" or healthy weight. Once you hit 25.0, you're overweight, and anything over 30.0 lands you in the obesity categories.

It’s efficient. Doctors love it because it’s fast. In a fifteen-minute appointment, they need a screening tool that takes three seconds to calculate.

But the height weight body mass index chart is basically just a ratio. It assumes an "average" body composition that often doesn't exist in the real world. Think about a professional rugby player or a heavy-duty weightlifter. These athletes often have BMI scores that scream "obese," despite having body fat percentages in the single digits. Their bones are denser. Their muscle mass is off the charts. The math simply breaks when applied to them.

Then you have the opposite problem: "skinny fat" or metabolically obese normal weight (MONW). This is where someone has a "healthy" BMI but carries high levels of internal fat around their organs. This person might actually be at higher risk for Type 2 diabetes than someone categorized as overweight who has a lot of leg muscle.

Why Your Doctor Still Uses It

Despite the flaws, the medical community hasn't ditched the chart. Why? Because on a massive, population-wide scale, it actually correlates pretty well with health risks. If you look at 100,000 people, those with a BMI over 30 generally have higher rates of cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome.

It's a red flag. Not a diagnosis.

When a physician looks at a height weight body mass index chart, they should be using it as a conversation starter, not a final verdict. It’s the "smoke" that leads them to look for the "fire." If your BMI is high, they should follow up with blood pressure checks, cholesterol panels, and maybe a waist circumference measurement.

Interestingly, researchers like Dr. Francisco Lopez-Jimenez at the Mayo Clinic have pointed out that waist-to-hip ratio is often a much better predictor of heart health than BMI. Why? Because where you store your fat matters way more than how much you weigh. Fat stored right under the skin on your hips (subcutaneous) is mostly cosmetic. Fat stored deep in your abdomen (visceral) is biologically active—it pumps out inflammatory chemicals that mess with your insulin and your heart.

The Limits of the Chart for Different Ethnicities

One of the biggest criticisms of the standard BMI chart is its lack of diversity. The original "normal" ranges were based largely on data from people of European descent. This is a huge problem.

- Asian populations: Research has shown that people of South and East Asian descent often face higher risks of diabetes and heart disease at lower BMI levels. Because of this, many health organizations suggest that for these groups, the "overweight" cutoff should actually be 23.0, not 25.0.

- Black populations: Conversely, some studies suggest that the relationship between BMI and mortality is different for Black individuals, particularly women. There is evidence that higher BMIs may not carry the same metabolic risk in these groups as they do in white populations, possibly due to differences in where fat is stored and bone mineral density.

Moving Beyond the Grid

If we stop obsessing over the height weight body mass index chart, what should we look at instead?

💡 You might also like: When Eligible for Medicare: The Checklist Most People Miss

Functional health is a great place to start. Can you walk up three flights of stairs without feeling like your lungs are on fire? Is your resting heart rate trending down? How's your sleep? These are markers of vitality that a scale can't capture.

There's also the DEXA scan. Usually used for bone density, it’s the gold standard for body composition. It tells you exactly how much of you is bone, how much is muscle, and how much is fat. It’s expensive, though, and not something you’ll do every Tuesday. A cheaper alternative is the "string test." Cut a piece of string to your height. Fold it in half. If it fits around your waist comfortably, you’re likely in a good spot metabolically, regardless of what the BMI chart says.

We also have to talk about the "Obesity Paradox." It sounds fake, but it’s a real phenomenon observed in medical literature. In some cases, particularly among the elderly or those with chronic kidney disease, having a slightly higher BMI (falling into the "overweight" category) is actually associated with better survival rates than being in the "normal" range. This suggests that a little extra reserve can be protective during serious illness.

The Psychological Toll

Let's be real: being told you're "Grade 1 Obese" because of a height-to-weight ratio can be demoralizing. It ignores your effort. It ignores your context.

If you've been powerlifting for three years and your BMI goes up, that's usually a win. But the chart sees it as a loss. This narrow focus can lead to weight cycling (yo-yo dieting), which is arguably worse for your heart than just staying at a stable, slightly higher weight. Stress hormones like cortisol spike when we're constantly fighting the scale, and ironically, cortisol makes us hold onto abdominal fat.

Actionable Steps for Navigating Your Health

Don't throw your scale out the window just yet, but do change how you interpret the data.

✨ Don't miss: What Does Turmeric Do for You? The Reality Behind the Golden Latte Hype

- Contextualize your BMI: Use the chart as a baseline, but don't let it be the boss of you. If your BMI is high, look at your waist circumference. For men, a waist over 40 inches and for women, over 35 inches, is usually a more urgent sign than the BMI number itself.

- Request a Full Metabolic Panel: If your doctor brings up your BMI, ask for blood work. Your fasting glucose, HbA1c, and triglyceride-to-HDL ratio tell a much deeper story about your internal health than your gravitational pull on the earth.

- Focus on "Non-Scale Victories": Track your strength, your flexibility, and your energy levels. If you’re getting stronger and your clothes fit better, but the height weight body mass index chart says you haven't moved, trust your body over the math.

- Consider Body Volume Index (BVI): Some modern clinics are moving toward BVI, which uses 3D body scanning to measure how much fat is actually in the abdominal cavity versus the limbs. It’s a more sophisticated way to use technology to see what’s actually going on.

- Audit Your Lifestyle, Not Just Your Weight: Are you getting 7-9 hours of sleep? Are you managing stress? Are you eating whole foods? If those answers are yes, your BMI is a secondary concern.

Health is a massive, complex puzzle. The BMI chart is just one tiny, slightly pixelated piece of it. Treat it as a starting point, not the finish line. Focus on the habits you can control today—like a 20-minute walk or adding a serving of greens to your dinner—rather than a number that was invented before lightbulbs existed.