Robert Mitchum didn't exactly do "soft." Whether he was playing a psychotic preacher or a weary detective, the guy had this heavy-lidded, cynical energy that made you feel like he'd seen it all twice and wasn't impressed either time. But if you're looking for the quintessential Robert Mitchum shipwreck movie, you’re almost certainly thinking of John Huston’s 1957 classic, Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison.

It’s a weird setup on paper. A rugged, illiterate Marine corporal and a devout nun are trapped together on a Pacific island during World War II. Sounds like the start of a bad joke or a really cheesy melodrama. Instead, it’s one of the most grounded, respectful, and oddly tense survival stories ever put to film.

Mitchum plays Corporal Allison. He’s a guy who literally calls the Marine Corps his mother and father. After a disastrous escape from a Japanese-controlled area, he drifts in a small rubber raft—sunburned, dehydrated, and basically at death's door—until he hits the shores of Tuasivi Island. He thinks he’s found a deserted paradise. He hasn't. He finds Sister Angela, played by Deborah Kerr, who’s been left behind after the local mission was evacuated.

The movie works because it doesn't take the easy way out. There's no immediate romance, no "Beauty and the Beast" transformation. It’s just two people from completely opposite universes trying not to get killed by the Japanese Imperial Army or their own basic instincts.

The Making of a Tropical Nightmare

People forget how difficult it was to film on location in the late fifties. This wasn't a green-screen job in a cooled studio in Burbank. Huston moved the entire production to Trinidad and Tobago. It was hot. It was buggy. It was miserable.

Mitchum was famous for being a "one-take" actor who pretended he didn't care about the craft, but the physical toll of this Robert Mitchum shipwreck movie was real. He did most of his own stunts, including some pretty gnarly scenes where he’s dragging himself through razor-sharp coral and thick mud. There’s a scene where he has to kill a sea turtle for food—it's visceral and desperate. You can see the grime under his fingernails. That wasn't just makeup; that was the reality of filming in the Caribbean humidity.

Honestly, the chemistry between Mitchum and Kerr is what saves the film from becoming a boring survivalist procedural. They had worked together before and would work together again in The Sundowners, but here, the friction is palpable. Mitchum’s Allison is a man of the flesh; Kerr’s Sister Angela is a woman of the spirit. When the Japanese establish a base on the island, the two are forced into a cramped cave.

📖 Related: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

That’s where the movie shifts from a shipwreck adventure into a psychological thriller.

Why This Isn't Your Average Survival Film

Most shipwreck movies focus on the "how." How do they build a fire? How do they catch fish? Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison focuses on the "who."

Allison is a man who understands violence and hierarchy. He knows how to survive a war, but he has no idea how to talk to a woman who has dedicated her life to God. He’s respectful, sure, but he’s also a human being with needs. There’s a genuinely uncomfortable moment where Allison, fueled by stolen saké and the sheer loneliness of their situation, basically tells her that her vows don't matter because they’re likely going to die anyway.

It’s a heavy scene. It’s not "Hollywood" heavy; it’s "real-life" heavy.

The Japanese Presence and the Tension of Discovery

The stakes get cranked up once the island is no longer "just" a prison. The Japanese Navy arrives and sets up a weather station. Now, our shipwrecked duo isn't just fighting hunger; they’re playing a high-stakes game of hide-and-seek.

- The Cave: This becomes their entire world. The cinematography by Oswald Morris uses the darkness to emphasize their isolation.

- The Foraging: Allison has to sneak into the Japanese camp to steal food. These sequences are shot with almost no dialogue, relying entirely on Mitchum’s physical presence.

- The Bombardment: When the Americans finally show up, it’s not an immediate rescue. It’s a terrifying artillery barrage that puts the protagonists in more danger than they were in before.

The film handles the Japanese characters with more nuance than many 1950s war films, though they are still largely an abstract "threat." The focus stays locked on the two Westerners and their internal struggles.

👉 See also: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

The "Mitchum" Factor in Shipwreck Cinema

What makes a Robert Mitchum shipwreck movie different from, say, a Tom Hanks or a Castaway-style story? It's the cynicism. Mitchum never plays a victim. Even when he's shipwrecked, he looks like he's just waiting for a chance to punch the ocean in the face.

He was an actor who excelled at "doing nothing" while actually doing a lot. In Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison, he uses his body to convey the slow breakdown of a professional soldier. His walk changes. His voice gets raspier. By the end of the film, he looks less like a Marine and more like a part of the island itself.

There's a specific scene where he's watching Sister Angela from a distance. He doesn't say a word. But you can see the conflict in his eyes—the realization that he loves her, and the simultaneous realization that he can never have her. That kind of subtle acting is why Mitchum remains a legend. He didn't need a five-minute monologue to tell you he was heartbroken. He just squinted.

Fact-Checking the Production

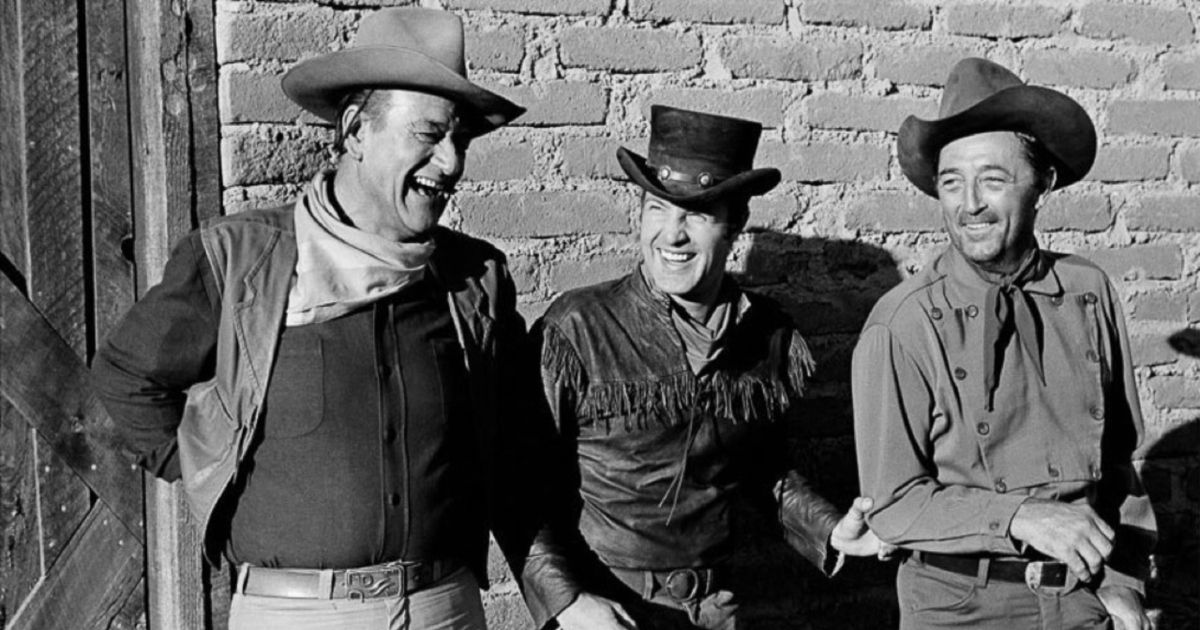

There are a lot of myths about this movie. One common story is that Mitchum and Huston hated each other. That’s not really true. They were both "men's men" who liked to drink and tell stories. In fact, Mitchum reportedly had a lot of respect for Huston’s willingness to get into the muck with the crew.

Another interesting fact: The Catholic Legion of Decency was hovering over this production like a hawk. They were terrified that the movie would suggest a sexual relationship between a Marine and a nun. Huston had to walk a very fine line to keep the tension high without actually breaking any of the strict production codes of the era.

The result is a film that feels much more erotic and intense because of what isn't shown. The restraint makes the connection between Allison and Angela feel more profound. It’s about two souls connecting in a vacuum where the rest of the world has ceased to exist.

✨ Don't miss: Is Steven Weber Leaving Chicago Med? What Really Happened With Dean Archer

Other Mitchum "Nautical" Moments

While Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison is the big one, Mitchum was no stranger to the water.

- The Night of the Hunter: Not a shipwreck movie, but the scenes of the children floating down the river in a skiff have that same "adrift and in danger" vibe.

- The Enemy Below: Released the same year (1957). Mitchum plays a destroyer captain playing cat-and-mouse with a German U-boat. It’s not a shipwreck story, but it’s the definitive Mitchum "sea" movie.

- The Sea Wall: A later, lesser-known film where he deals with the encroaching ocean in Indo-China.

None of these quite capture the "man against nature" desperation of the Allison story, though.

The Impact on Modern Cinema

You can see the DNA of this Robert Mitchum shipwreck movie in everything from Six Days, Seven Nights (the "fun" version) to The Revenant (the "miserable" version). The idea of stripping a character down to their barest elements by removing the safety net of civilization is a trope for a reason. It works.

But Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison does it with a grace that modern movies often lack. It’s not interested in being a "survivalist's handbook." It’s interested in what happens to your soul when you’re stuck on a rock in the middle of the Pacific with someone you’re not supposed to love.

How to Watch and What to Look For

If you’re going to sit down and watch this today, don’t expect a fast-paced action flick. It’s a slow burn.

- Watch the eyes: Both Mitchum and Kerr do their best work when they aren't talking.

- Listen to the score: Georges Auric’s music is understated but perfectly highlights the loneliness of the island.

- Pay attention to the color: The Technicolor is gorgeous but used purposefully to show the contrast between the lush jungle and the grey, sterile Japanese installations.

Actionable Insights for Classic Film Fans

If you're diving into the world of Robert Mitchum or 1950s survival cinema, here's how to get the most out of the experience:

- Pair it with The Enemy Below: Watching these two 1957 films back-to-back gives you a masterclass in Mitchum’s range. You see him as the rugged, uneducated grunt in Allison and then as the hyper-intelligent, weary commander in Enemy.

- Read the Source Material: The movie is based on a novel by Charles Shaw. Comparing the book to the film reveals just how much Huston leaned into the "spiritual" aspect of the story to get past the censors.

- Check out the Location: If you're a travel buff, the beaches of Tobago where this was filmed are still largely recognizable. Monos Island, off the coast of Trinidad, served as the primary backdrop.

- Look for the "Huston Touch": John Huston was obsessed with "the loser." Most of his movies are about people who fail or who win a hollow victory. Look at the ending of Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison through that lens—is it really a "happy" ending?

Whether you call it a Robert Mitchum shipwreck movie or a high-stakes theological drama, Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison remains a powerhouse of mid-century filmmaking. It’s a reminder that you don't need a thousand extras or a hundred million dollars in CGI to tell a story that feels massive. You just need two great actors, a bit of mud, and a script that understands the human heart.