You're probably here because something happened. Maybe you took a nasty spill off a bike, or your kid bumped their forehead on the coffee table and now there's a "goose egg" that looks terrifying. Naturally, you grabbed your phone. You typed in head injury pictures images to see if that purple-ish knot or that tiny bit of road rash matches the horror stories on the internet.

It's a gut reaction. We want visual confirmation that we’re okay. But honestly? Looking at photos of head trauma online is a bit of a double-edged sword.

External damage often has almost zero correlation with what's actually happening inside the skull. You could have a scalp wound that looks like a scene from a slasher flick—because the scalp is incredibly vascular and bleeds like crazy—and be totally fine. Conversely, someone could have a pristine-looking forehead but be dealing with a life-threatening intracranial hemorrhage.

The disconnect between the "outside" and the "inside" is why doctors get so twitchy when patients rely on Google Images for a self-diagnosis.

The problem with searching for head injury pictures images

When you scroll through search results for head injury pictures images, you're mostly seeing the extremes. You see the massive hematomas, the surgical scars from craniotomies, or the classic "raccoon eyes" (periorbital ecchymosis) that signal a basal skull fracture.

These images are jarring. They trigger your fight-or-flight response.

But they don't show you the nuance of a Grade 1 concussion. They don't show you the "talk and die" syndrome, where a person appears perfectly lucid after a hit—maybe they even look fine in a selfie—only to collapse hours later because an epidural hematoma is slowly putting pressure on their brain.

Why the "Visuals" lie to you

The scalp is thick. It's tough. It’s also packed with blood vessels. Even a tiny nick can result in a significant amount of blood, which looks horrific in a photo.

🔗 Read more: Why Doing Leg Lifts on a Pull Up Bar is Harder Than You Think

On the flip side, the brain is soft. It has the consistency of soft butter or firm gelatin. When the head stops suddenly, the brain keeps moving, slamming against the internal ridges of the skull. No camera can capture that shear strain.

Dr. Robert Cantu, a leading expert on concussions and a co-founder of the Medical Health Legacy Foundation, has spent decades explaining that "clinical symptoms" trump "visual evidence" every single time. If you’re looking at head injury pictures images to decide if you should go to the ER, you're already using the wrong metric.

What you are actually seeing in those photos

Let's break down what those common images actually represent. Most of the time, the stuff that looks the scariest is just "plumbing."

- The Goose Egg (Hematoma): This is just blood pooling under the skin but outside the skull. It looks like a cartoon bump. In most cases, if it's squishy and limited to the forehead, it's just a bruise with nowhere to go but out.

- Lacerations: Scalp tears. They bleed a lot. They need stitches or staples. But unless the bone underneath is cracked, they aren't "brain injuries."

- Battle's Sign: If you see an image of bruising behind the ear, that’s serious. It's often a sign of a break in the bottom of the skull. This is where the internet actually helps—knowing that "bruise behind ear = bad" is a lifesaver.

The stuff you can't see

A concussion is a functional injury, not a structural one.

Think of it like this: your hardware (the skull and brain tissue) might look perfect on an MRI or in a photograph, but the software (the way neurons communicate) is glitching. This is why many professional athletes look fine on the sidelines after a hit but can't remember what day it is.

The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) Sports Medicine Concussion Program emphasizes that there are actually six different "types" of concussions. Some affect your eyes, some your balance, some your mood. None of them show up well in head injury pictures images.

When the image matters: Documenting for doctors

There is one scenario where taking your own head injury pictures images is actually a smart move.

💡 You might also like: Why That Reddit Blackhead on Nose That Won’t Pop Might Not Actually Be a Blackhead

Documentation.

If you or a loved one hits their head, take a quick photo of the site. Do it under clear lighting. Why? Because bruises change. Swelling evolves. When you finally get to an Urgent Care or the ER, showing the doctor a photo of how the injury looked 10 minutes after the impact can help them understand the force involved.

It’s about the progression.

Is the swelling getting wider? Is the color changing rapidly? Is there fluid—specifically clear or pinkish fluid—leaking from the nose or ears? If you capture that in a photo, show it to a nurse immediately. That "clear fluid" could be Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF), and that's a medical emergency.

The "Danger Zone" symptoms that don't have a look

Honestly, you should stop looking at the screen and start looking at the person.

The CDC's "HEADS UP" campaign is the gold standard here. They don't tell you to look for a specific type of bruise. They tell you to look for behaviors.

- Repeated vomiting. Not just once from the shock, but persistent throwing up.

- One pupil larger than the other. This is a classic sign of brain swelling or a clot.

- Can't wake up. If they are unusually drowsy, stop searching for photos and call 911.

- Slurred speech. They sound drunk but haven't had a drop to drink.

- Seizures. Even if it's just a brief "blanking out" or twitching.

If you’re seeing these, the most high-definition head injury pictures images in the world won't help you as much as a CT scan will.

📖 Related: Egg Supplement Facts: Why Powdered Yolks Are Actually Taking Over

The trap of "Comparative Diagnosis"

We all do it. We look at a photo of someone else's injury and think, "Oh, mine doesn't look that bad. I'm fine."

This is dangerous.

The human skull varies in thickness. The mechanism of injury matters—was it a fall from standing height or a car accident? A 10-year-old’s brain reacts differently to impact than an 80-year-old’s brain (which might have more "room" to move inside the skull due to natural shrinkage, leading to torn veins).

I’ve seen cases where a minor "fender bender" bump caused a subdural hematoma in an elderly patient because their veins were more fragile. A photo of that bump would have looked like nothing.

Actionable steps for the next 24 hours

If you’ve just searched for head injury pictures images because of a recent accident, stop scrolling through the gallery and do this instead:

- Check the pupils. Use a flashlight. Do they both shrink when the light hits them? Are they equal in size?

- Test the memory. Ask three questions. "Where are we?" "What happened?" "Who is the President?" If they struggle with these, it's a concussion until proven otherwise.

- Monitor for the "Gap." Sometimes people feel fine for an hour (the lucid interval) and then crash. Don't leave them alone for the first 4 to 6 hours.

- Physical Rest. No gym. No running. No "powering through."

- Cognitive Rest. This is the hard one. Put the phone away. Stop looking at head injury pictures images. The light and the mental effort of processing the search results can actually make concussion symptoms worse.

Moving forward

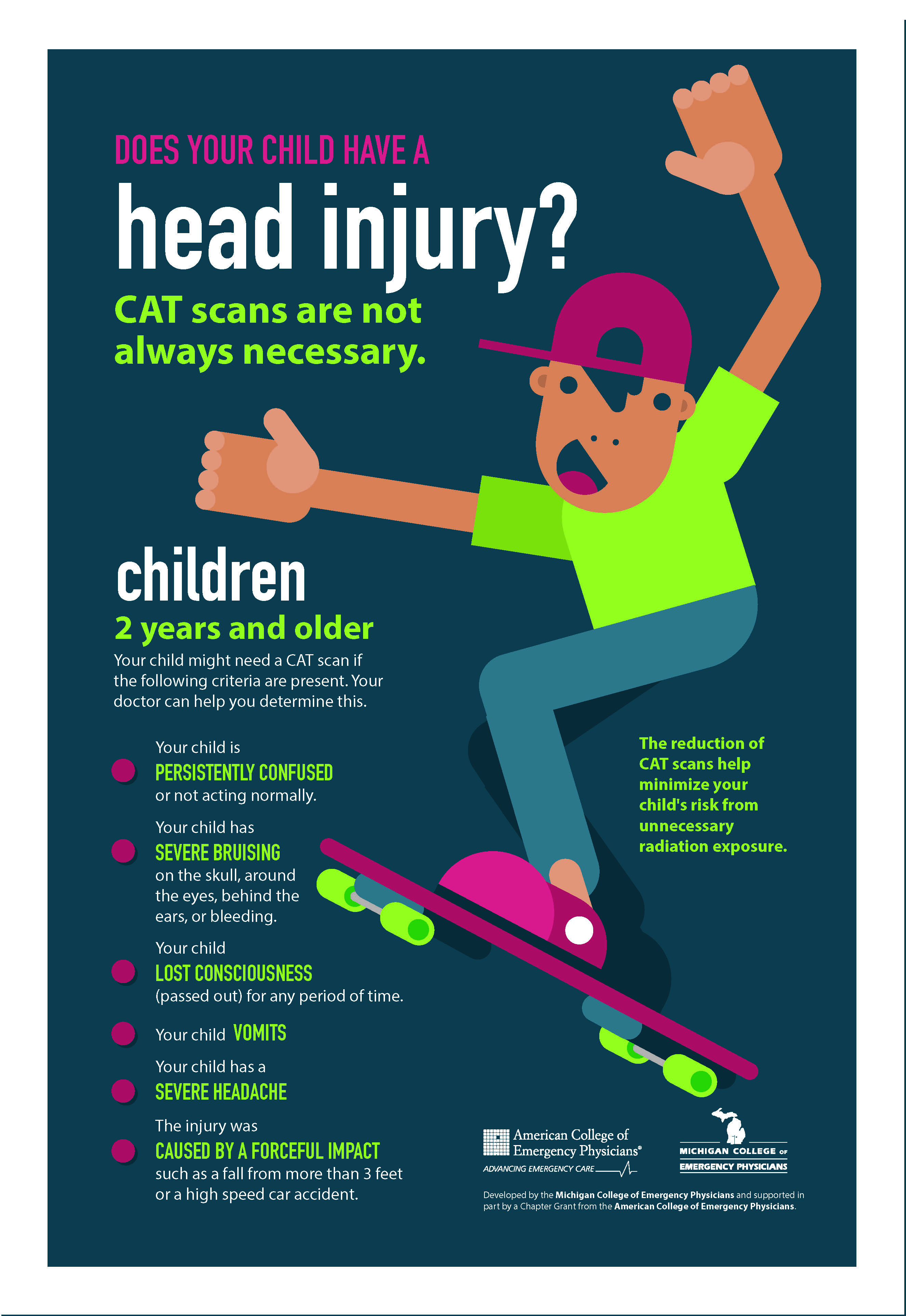

If the injury happened to a child, follow the "when in doubt, check it out" rule. Pediatricians are used to these calls. They would much rather tell you it’s just a bump than see the child in the ICU two days later.

For adults, use your head—literally. If you feel "off," have a splitting headache that won't go away with Tylenol, or feel like the world is spinning, the internet's library of images has served its purpose in getting you to pay attention.

Now, go see a professional.

Key takeaways for your safety:

- Visual severity rarely equals internal brain injury severity.

- Clear fluid from ears or nose is an immediate emergency.

- Document your own injury via photo to show the progression to a doctor.

- Prioritize behavioral symptoms (confusion, vomiting, pupil size) over the appearance of a bruise.