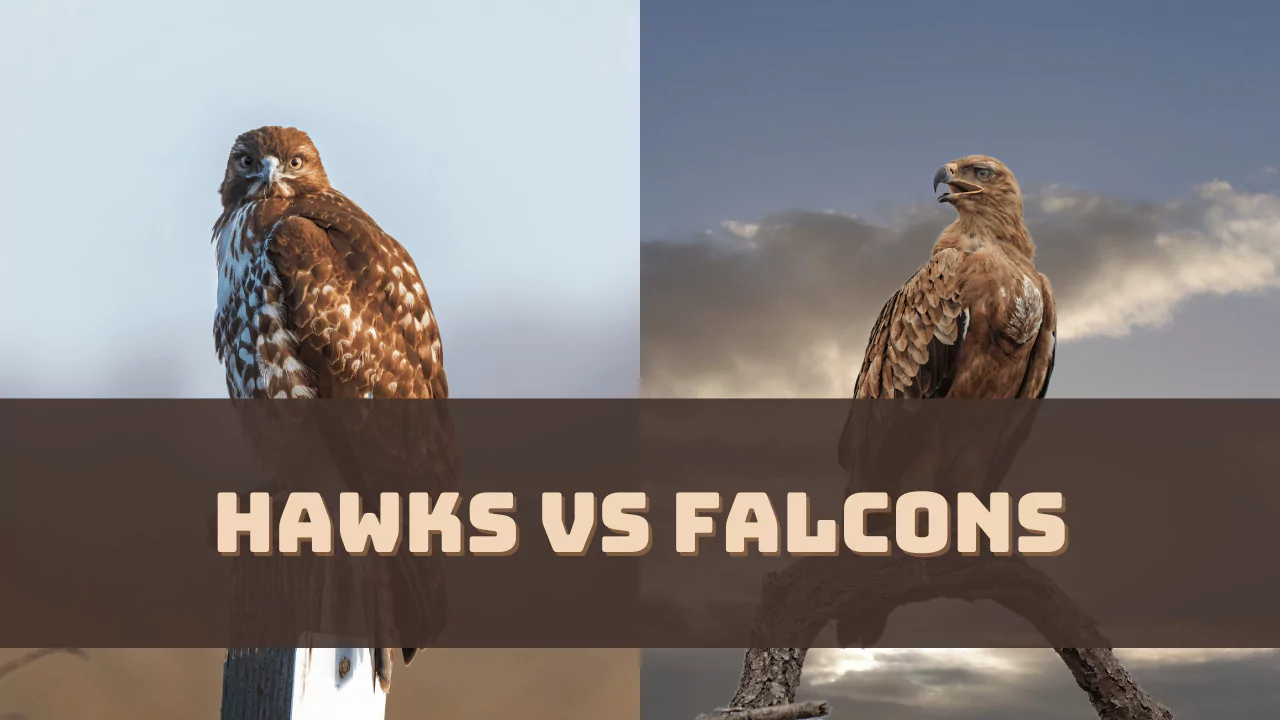

You're standing in an open field, squinting at a dark speck against the clouds. It’s moving fast. Too fast for a crow, too deliberate for a gull. Is it a hawk? Or maybe a falcon? Most people use the names interchangeably, but honestly, that’s like calling a mountain bike a Ducati. They both have wheels, sure, but they’re built for entirely different worlds.

If you’ve ever felt confused trying to settle the hawks vs falcons debate while looking through binoculars, don't worry. Even seasoned birders sometimes double-check the wing shape before making the call.

The Wing Shape is the Dead Giveaway

Look at the silhouette. This is the fastest way to tell them apart without needing a PhD in ornithology. Hawks generally have short, wide, rounded wings. They’re built for maneuverability in the woods. Think about a Red-tailed Hawk—it needs to bank hard around an oak tree to snag a squirrel. It’s all about lift and steering.

Falcons are a different breed. Their wings are long, slender, and pointed. They look like the letter "V" or a pair of scythes cutting through the air. This shape is designed for one thing: pure, unadulterated speed. While a hawk is a rugged SUV built for off-roading, a falcon is a Formula 1 car. They don't want to maneuver through thick brush; they want to dive through the open sky at speeds that would get you a massive ticket on the interstate.

The Peregrine Falcon is the celebrity of this group. When it goes into a "stoop"—that’s basically a high-speed vertical dive—it can hit over 200 mph. National Geographic once clocked a bird named Frightful at 242 mph. Hawks can’t even touch that. A Red-tailed Hawk might hit 120 mph in a dive, which is impressive, but it’s still getting left in the dust.

How They Kill (It’s a Bit Gory)

This is where things get really interesting, and a little dark. They have totally different philosophies on how to end a hunt.

Hawks are all about the feet. They have incredibly powerful talons and massive grip strength. When a Cooper’s Hawk hits a bird, it uses those long legs and sharp claws to squeeze. They basically "knead" their prey until it stops moving. It’s a brute-force method. Their beak is mostly for tearing meat afterward, not for the initial kill.

Falcons have a "tooth." Well, sort of. If you look closely at a falcon’s beak—like a Kestrel or a Gyrfalcon—you’ll see a little notch on the upper mandible. It’s called a tomial tooth. Because falcons hit their prey at such high speeds, they often knock the other bird out of the sky mid-air. Once they ground the prey, they use that specialized notch in their beak to quickly sever the neck vertebrae. It’s surgical. It’s efficient. It’s very "assassin-style" compared to the hawk’s "wrestler" approach.

The Eye Color Secret

Have you ever noticed that most falcons look like they’re wearing heavy eyeliner? They often have dark "malar stripes" under their eyes, which scientists believe act like the black grease football players wear to reduce glare from the sun. Their eyes are almost always very dark, appearing nearly black.

Hawks are a different story. Many hawks, especially the Accipiters like Sharp-shinned Hawks, start life with bright yellow eyes. As they get older, those eyes turn deep orange or even a blood-red. It gives them a very piercing, intense stare that feels like they’re looking right through you. If you see a raptor with bright yellow or red eyes, you’re almost certainly looking at a hawk, not a falcon.

Where They Hang Out

Taxonomy tells us something weird. For a long time, we thought hawks and falcons were close cousins. We were wrong. Recent DNA studies—specifically a massive 2008 study published in Science—revealed that falcons are actually more closely related to parrots and songbirds than they are to hawks. Evolution just made them look similar because they do similar jobs. This is called convergent evolution.

Because they aren't actually that related, they prefer different neighborhoods.

- Hawks (Buteos and Accipiters): You’ll find them in forests, along tree-lined highways, and in suburban backyards. They love a good perch. If you see a big, chunky bird sitting on a telephone pole or a fence post waiting for a mouse to twitch, that’s your hawk.

- Falcons: These guys like the high ground or wide-open spaces. Peregrines famously love skyscrapers in New York City or Chicago because the ledges mimic the high cliffs where they naturally nest. They also love the wind. You’ll see smaller falcons, like American Kestrels, hovering in place over a field—a trick most hawks can't pull off.

The Size Myth

Don't fall into the trap of thinking all hawks are big and all falcons are small. Size is a terrible way to settle the hawks vs falcons question.

Sure, a Gyrfalcon is huge—it’s the largest falcon in the world and can weigh over three pounds. Meanwhile, a Sharp-shinned Hawk is tiny, sometimes no bigger than a large blue jay. You have to look at the proportions. Falcons almost always have a shorter tail relative to their body and those distinctively pointed wings. Hawks often have longer, rudder-like tails that help them steer through the tight gaps in forest canopies.

Understanding the "Niche"

Think about the Cooper’s Hawk. If you have a bird feeder, you might hate this bird. It’s the one that streaks across your yard and grabs a mourning dove right off the deck. It’s a woodland specialist. Its short, rounded wings allow it to accelerate instantly.

Now, compare that to a Merlin (a small, feisty falcon). A Merlin doesn't sneak up through the trees. It spots a dragonfly or a small bird from a distance and just outruns it. It’s a pursuit predator. One is a ninja; the other is a sprinter.

Why Does This Even Matter?

Knowing the difference changes how you see the world. When you realize that the bird on the power line is a Red-tailed Hawk, you start to notice the ecology of your own neighborhood. You see the balance between the predators and the rodents.

🔗 Read more: Ladies Long Hairstyles With Fringe: Why Most Stylists Get the Cut Wrong

If you see a falcon in the city, you’re witnessing a miracle of adaptation—a bird that used to hunt over ancient canyons now using a 50-story glass office building to gain altitude for a 200 mph dive.

Identification Cheat Sheet for Your Next Walk

Next time you see a raptor, run through this mental checklist:

- Check the Wing Tips: Are they "fingered" (spread out like a hand) or pointed like a knife? Fingered means hawk; pointed means falcon.

- Watch the Flight: Is it flap-flap-glide? Probably a hawk. Is it a constant, rapid wingbeat like a pigeon on steroids? Likely a falcon.

- Look at the Head: Is there a "mustache" or dark stripe under the eye? That's the falcon's signature look.

- The Tail Factor: Long and narrow usually suggests a hawk (especially Accipiters). Short and tapered often points toward a falcon.

Getting Started with Raptor Watching

If you really want to dive into this, stop relying on random Google images and get a proper field guide. The Sibley Guide to Birds is the gold standard for a reason. The illustrations show the birds in flight from underneath, which is exactly how you’ll see them 90% of the time.

Download the Merlin Bird ID app by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. It’s free and uses AI to help you identify birds by photo or even by their call. It’s incredibly accurate.

Go to a "Hawk Watch" site during migration season (typically fall or spring). There are spots like Hawk Mountain in Pennsylvania or the Goshute Mountains in Nevada where thousands of these birds fly over a single ridge in a day. You’ll have experts standing right next to you who can point out the subtle difference between a Broad-winged Hawk and a Prairie Falcon from a mile away.

Lastly, buy a decent pair of binoculars. You don't need to spend $2,000 on Swarovski glass, but a solid $150 pair of 8x42 binoculars will change your life. You’ll suddenly see the yellow of the eye, the notch in the beak, and the "eyeliner" that makes the distinction clear. Once you see it, you can't unsee it. You'll never look at a "big brown bird" the same way again.