You probably think you know the Little Mermaid. You’ve seen the red hair, the singing crab, and the "happily ever after" where she marries the prince and lives in a castle. Honestly, if you went back to 1837 and told Hans Christian Andersen that version of his story, he’d probably just stare at you in confused silence.

The real Hans Andersen fairy tales are brutal. They aren’t just "stories for kids" in the way we think of them now; they are psychological explorations of loneliness, social class, and faith. When Andersen wrote The Little Mermaid, it wasn't a romance. It was a tragedy about a soul. The mermaid doesn’t get the guy. In fact, she watches him marry someone else, and every step she takes on her human legs feels like she's walking on sharp knives. That's the vibe of the original material. It's raw. It's painful. And it's deeply, deeply weird.

Why we keep misinterpreting Hans Andersen fairy tales

Most of us grew up with the Disney-fied versions. There is nothing wrong with that—they're great movies—but they strip away the "Andersen" of it all. Andersen wasn't a comfortable man. He was an outsider in Danish society, the son of a shoemaker and a washerwoman, constantly trying to fit into the high-society circles of Copenhagen. You can see this tension in almost every one of the Hans Andersen fairy tales.

Take The Ugly Duckling. People treat it as a "be yourself" anthem. But look closer. The duckling doesn’t become a swan because he believes in himself; he becomes a swan because he was always a swan. He just had to survive the winter without dying of hypothermia or being beaten to death by farm animals. It’s a story about biological inevitability and the cruelty of the "lower" classes, reflecting Andersen's own struggle to be accepted by the literary elite. He felt like a different species.

Then there’s The Red Shoes. This one is straight-up horror. A girl is so vain about her red shoes that they become cursed and won't stop dancing. She eventually has to ask an executioner to chop off her feet with an axe. The feet—still in the shoes—continue to dance away into the forest. This isn't a "light" moral lesson. It’s a terrifying look at obsession and divine punishment. If you read these to a toddler today, you’d probably get a call from a therapist. But in the 19th century, this was the standard.

🔗 Read more: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

The Man Behind the Myth

Hans Christian Andersen was a tall, gangly, deeply insecure man. He never married. He had intense, often unrequited crushes on both men and women—most famously the Swedish opera singer Jenny Lind, for whom he supposedly wrote The Nightingale. His travel journals are full of anxiety. He was terrified of fires and always carried a coil of rope in his luggage so he could escape from hotel windows.

This anxiety permeates his work. When you read Hans Andersen fairy tales, you aren't just reading folk stories. Unlike the Brothers Grimm, who mostly collected existing oral traditions and polished them up, Andersen invented most of his plots from scratch. They are autographical. When the Steadfast Tin Soldier stands perfectly still while he melts in the fire, that’s Andersen’s vision of masculinity—suffering in silence while your heart breaks.

The weirdest details you probably missed

If you sit down with a complete collection of his works, you’ll find stories that make no sense to a modern audience.

- The Shadow: A man’s shadow detaches itself, becomes rich and successful, and eventually enslaves the man before having him executed. It’s a chilling commentary on identity and the falseness of public personas.

- The Girl Who Trod on the Loaf: A girl is so afraid of getting her shoes dirty that she steps on a loaf of bread to cross a puddle. She sinks into the mud, straight to the marsh-wife’s brewery, and becomes a living statue covered in slime and snakes.

- The Little Match Girl: We know this one is sad, but it’s often forgotten that it was written partly as a commentary on the extreme poverty Andersen saw in 1840s Europe. It’s a protest piece.

Andersen’s writing style was revolutionary for the time. He wrote in the way people actually spoke. In 19th-century Denmark, literary language was stiff and formal. Andersen used slang. He used exclamations. He talked directly to the reader like a friend. It’s why his stories survived when so many other "morality tales" of that era died out. They feel alive.

💡 You might also like: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

Faith and the Afterlife

You can’t talk about Hans Andersen fairy tales without talking about God. Andersen was a believer, but his version of Christianity was heavy on the "suffer now, get rewarded in heaven" side of things.

In The Little Mermaid, the whole point isn't the prince—it's the soul. Mermaids in his lore don't have immortal souls; they just turn into sea foam. The Little Mermaid wants to live forever in the afterlife. Even after she fails to win the prince and dies, she becomes a "daughter of the air," essentially doing 300 years of community service to earn a soul. The religious undertones are baked into the DNA of the narrative. Modern adaptations usually cut this because, well, it’s a bit of a buzzkill for a musical.

How to actually read Andersen today

If you want to experience these stories the right way, stop looking for the "message." Andersen wasn't a fan of simple morals. He liked the gray areas. He liked the idea that life is often unfair and that sometimes the "bad" guy wins, or at least the "good" guy loses everything before finding peace in death.

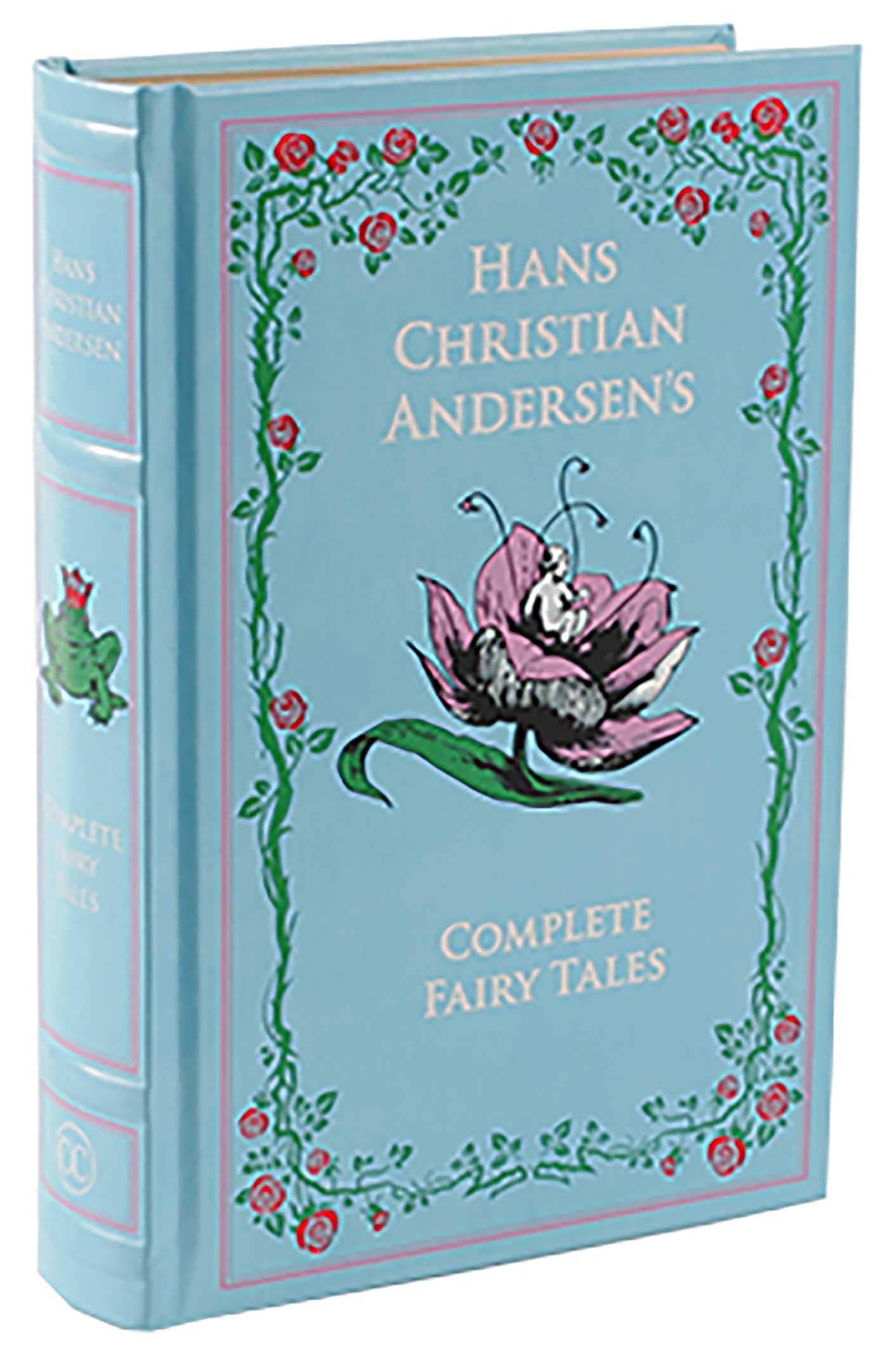

- Find an unabridged translation. Look for Jean Hersholt or Tiina Nunnally. They keep the weirdness intact. If the book looks too "precious," it's probably been sanitized.

- Read them out loud. These were meant to be performed. Andersen used to read them in the salons of wealthy patrons, acting out the parts. The rhythm of the prose comes alive when you hear it.

- Look for the satire. Many of his stories, like The Emperor's New Clothes, are biting critiques of the Danish middle class. He’s making fun of people who are too afraid to admit they don't know something.

Hans Christian Andersen changed literature because he proved that "children's stories" could be high art. He influenced everyone from Oscar Wilde to C.S. Lewis. He took the folk tradition and turned it into a mirror for the human psyche.

📖 Related: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

Actionable insights for the modern reader

- Audit your collection: Check if your children's books are "adapted" or "retold." If they are, you're missing about 70% of the actual story.

- Visit the source: If you ever find yourself in Odense, Denmark, the H.C. Andersen House museum is a trip. It doesn't treat him like a cartoon character; it treats him like the complex, troubled genius he was.

- Comparative reading: Pick one story, like The Snow Queen, and read the original alongside a modern adaptation (like Frozen). It’s a fascinating exercise in seeing what our modern culture is too "scared" to tell children. We've traded spiritual struggle for personal empowerment, and while that's fine, we've lost some of the haunting beauty Andersen brought to the table.

Start with The Shadow or The Nightingale. They aren't the most famous, but they are the most "Andersen." You'll see the bitterness, the yearning, and the incredible imagination that made Hans Andersen fairy tales a permanent part of the human experience. Don't expect a happy ending. Expect something much more interesting: the truth about being human.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

To truly appreciate the depth of Andersen’s work, seek out his travelogues like A Poet's Bazaar. They reveal the observational skills he used to build his fantasy worlds. Additionally, researching the "Golden Age of Danish Culture" provides the necessary context for why his social critiques were so scandalous—and necessary—at the time. Focus on the tension between his humble beginnings and his eventual fame, as this is the engine that drives almost every protagonist he ever created.