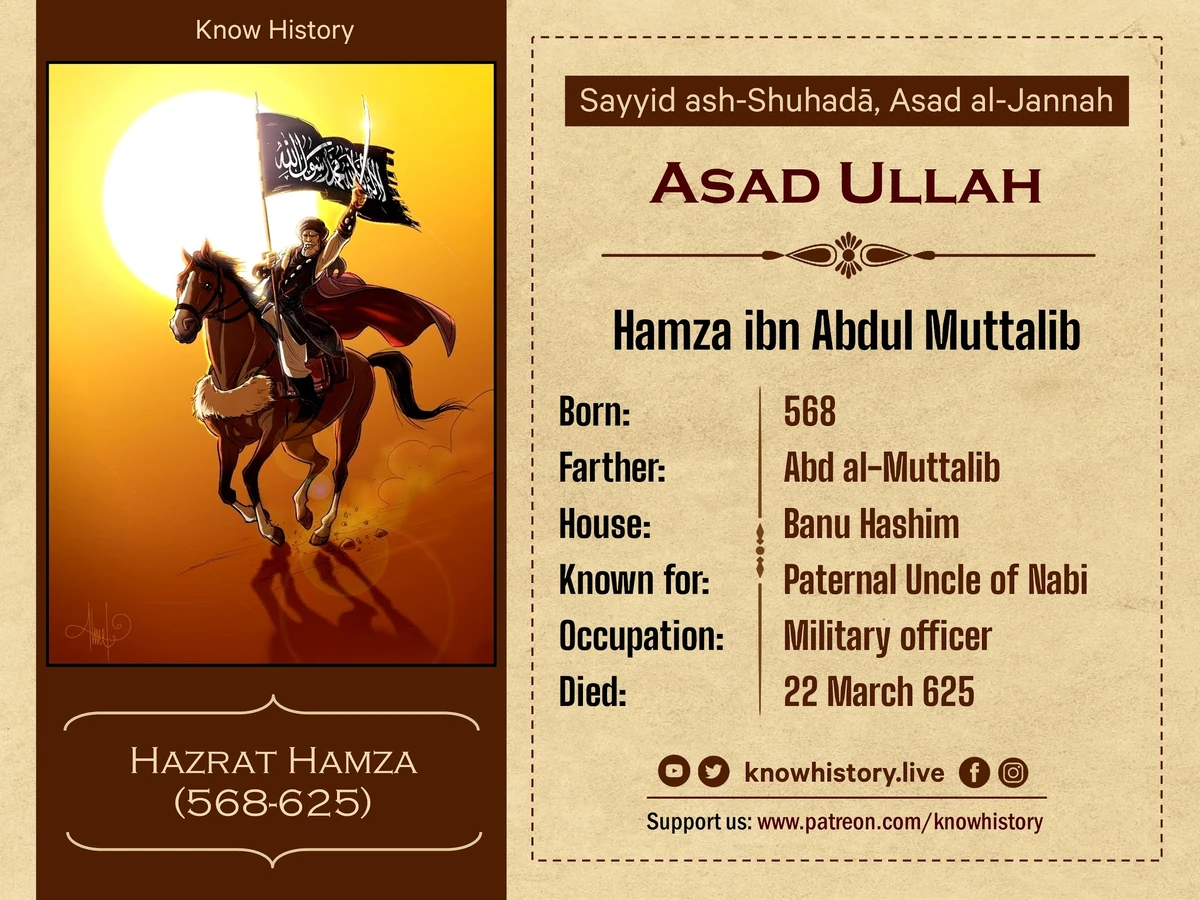

He wasn't just another warrior. If you look at the landscape of 7th-century Arabia, Hamza ibn Abd al-Muttalib stands out like a jagged mountain peak in a flat desert. He was the Prophet Muhammad's uncle, sure, but he was also his foster brother and his closest protector. People called him Asadullah—the Lion of God. It wasn't a marketing slogan. It was a description of a man who could walk into a room of hostile elites, strike a man across the face with a bow, and fundamentally shift the power dynamics of an entire region in a single afternoon.

Most people today know him through the lens of the 1976 film The Message, where Anthony Quinn played him with a sort of rugged, stoic intensity. But the real Hamza was even more complex. He was a hunter. He spent his days in the hills outside Mecca, tracking lions and sharpening his senses. This wasn't just a hobby; it was the training ground for the battles of Badr and Uhud that would define the early Islamic era.

The Moment Hamza ibn Abd al-Muttalib Changed History

It happened because of an insult. Honestly, history often turns on the smallest personal slights. Abu Jahl, a high-ranking Meccan leader who despised the new message of Islam, had been harassing Muhammad near the hill of Safa. He wasn't just debating theology; he was being nasty, hurling vitriol and insults.

Hamza wasn't even a Muslim yet.

He was returning from a hunting trip, bow slung over his shoulder, when a servant told him what had happened. Now, you have to understand the tribal code of the Quraysh. Honor was everything. Hamza didn't go home to process his feelings. He went straight to the Kaaba, found Abu Jahl sitting with his buddies, and cracked his heavy bow over the man's head.

"Will you insult him when I follow his religion?" Hamza challenged.

That was it. The declaration. It wasn't a quiet, meditative conversion in a dark room. It was a public, violent defense of his kin that forced him to commit to a path that would eventually lead to his death. His conversion gave the early Muslims a physical shield. Before Hamza, they were a persecuted minority hiding in the shadows. After Hamza—and later Umar ibn al-Khattab—joined, they could actually walk to the Kaaba and pray in the open.

✨ Don't miss: Williams Sonoma Deer Park IL: What Most People Get Wrong About This Kitchen Icon

The Strategy of a Desert Hunter

Hamza’s military value wasn't just about raw strength. It was about his specific skillset as a hunter. While others were used to the chaotic skirmishes of tribal raids, Hamza understood terrain, patience, and the psychological impact of a sudden strike.

At the Battle of Badr, which took place in 624 CE, he was one of the three men chosen for the initial duel—a custom where the best fighters from each side would face off before the main army engaged. He wore an ostrich feather in his turban. It was a "come and get me" signal. He dispatched his opponent with such speed that it rattled the Meccan ranks before the first arrow was even fired.

Historians like Ibn Ishaq note that Hamza fought with two swords at Badr. That takes an incredible amount of coordination and physical conditioning. He wasn't just swinging wildly. He was a calculated force of nature.

The Tragedy at Uhud and the Role of Wahshi

Success often breeds a very specific kind of resentment. The Meccans weren't just mad they lost at Badr; they were humiliated. And for Hind bint Utbah, the wife of the Meccan leader Abu Sufyan, it was deeply personal. Hamza had killed her father and her brother in the heat of battle.

She didn't want a fair fight. She wanted an assassination.

She hired an Ethiopian slave named Wahshi ibn Harb, who was an expert with the javelin. His only job was to track Hamza on the battlefield of Uhud and kill him. No other targets. No distractions. Just the Lion.

🔗 Read more: Finding the most affordable way to live when everything feels too expensive

The Battle of Uhud (625 CE) is often cited as a turning point in early Islamic history because it showed the consequences of breaking discipline. The Muslim archers on the hill left their posts, thinking the battle was won. In the ensuing chaos, Hamza was cutting through the enemy ranks. He tripped, or perhaps his foot slipped, and in that split second, Wahshi hurled his javelin from behind a rock.

It was a fatal hit.

Why the Details of His Death Matter

The aftermath of Hamza's death is one of the most gruesome and emotional chapters in the Seerah (prophetic biography). Hind reportedly mutilated his body. It was an act of raw, visceral vengeance that shocked even the hardened warriors of that era.

When Muhammad found his uncle’s body, the grief was overwhelming. It’s said he had never been so angry or so heartbroken. This wasn't just the loss of a general; it was the loss of the man who had been his protector when he had nobody else.

This moment led to a significant shift in Islamic ethics regarding warfare. While the initial impulse for many was to retaliate with equal brutality, the teachings that emerged emphasized restraint and the dignity of the deceased, even in war. It’s a nuance often lost in modern discussions about the era.

Debunking the Myths

You’ll often hear stories that Hamza was a giant or that he had supernatural powers. Let’s be real: he was a man. A very fit, very skilled, and very brave man, but a human nonetheless. The "supernatural" element comes from the sheer terror he inspired in his enemies.

💡 You might also like: Executive desk with drawers: Why your home office setup is probably failing you

Another misconception is that he was a late-life convert who only joined because of family ties. While family pride sparked his conversion, his subsequent years in Medina showed a man deeply committed to the spiritual and social reforms of the new faith. He wasn't just a "muscle" guy. He was involved in the community's growth and served as a bridge between the old aristocratic world of Mecca and the new egalitarian world of Medina.

What We Can Learn From the Lion of God

Hamza’s life offers a few "honestly, why don't we do this anymore?" moments for the modern world.

- The Power of Decisive Action. When Hamza saw an injustice, he didn't form a committee. He acted. While we don't advocate for hitting people with bows today, the principle of standing up for the vulnerable is timeless.

- Mastery of a Craft. Hamza was a master hunter long before he was a general. That foundational skill—patience, observation, physical fitness—translated into his later success. Whatever you do, master the base skills first.

- Loyalty Over Comfort. He could have stayed a high-ranking, wealthy Meccan noble. Instead, he chose a path that led to exile and an early grave because he believed in the person he was protecting.

Actionable Steps for Further Research

If you’re actually interested in the tactical history of this period or the biography of Hamza ibn Abd al-Muttalib, don't just stick to Wikipedia.

- Read "The Sealed Nectar" (Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum) by Safiur Rahman Mubarakpuri. It’s a standard text, but it provides the chronological context of the battles.

- Check out the primary sources. Look for translated excerpts of Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah. It’s the oldest surviving biography of Muhammad and gives the most "on the ground" feel of the 7th century.

- Study the Geography. Look at topographical maps of the Uhud battlefield. Seeing where the archers were stationed versus where the cavalry charge happened makes Hamza’s final moments much clearer.

Hamza’s legacy isn't just about the battles. It's about a specific type of courage—the kind that doesn't wait for the tide to turn before jumping in. He was a man of his time, shaped by the harsh realities of the desert, but his character remains a focal point for millions who see him as the ultimate example of what it means to be a protector.

He lived as a lion and died as a martyr, leaving behind a name that still carries weight fourteen centuries later. Understanding Hamza is basically a masterclass in how one person's refusal to be silent can change the course of an entire civilization.