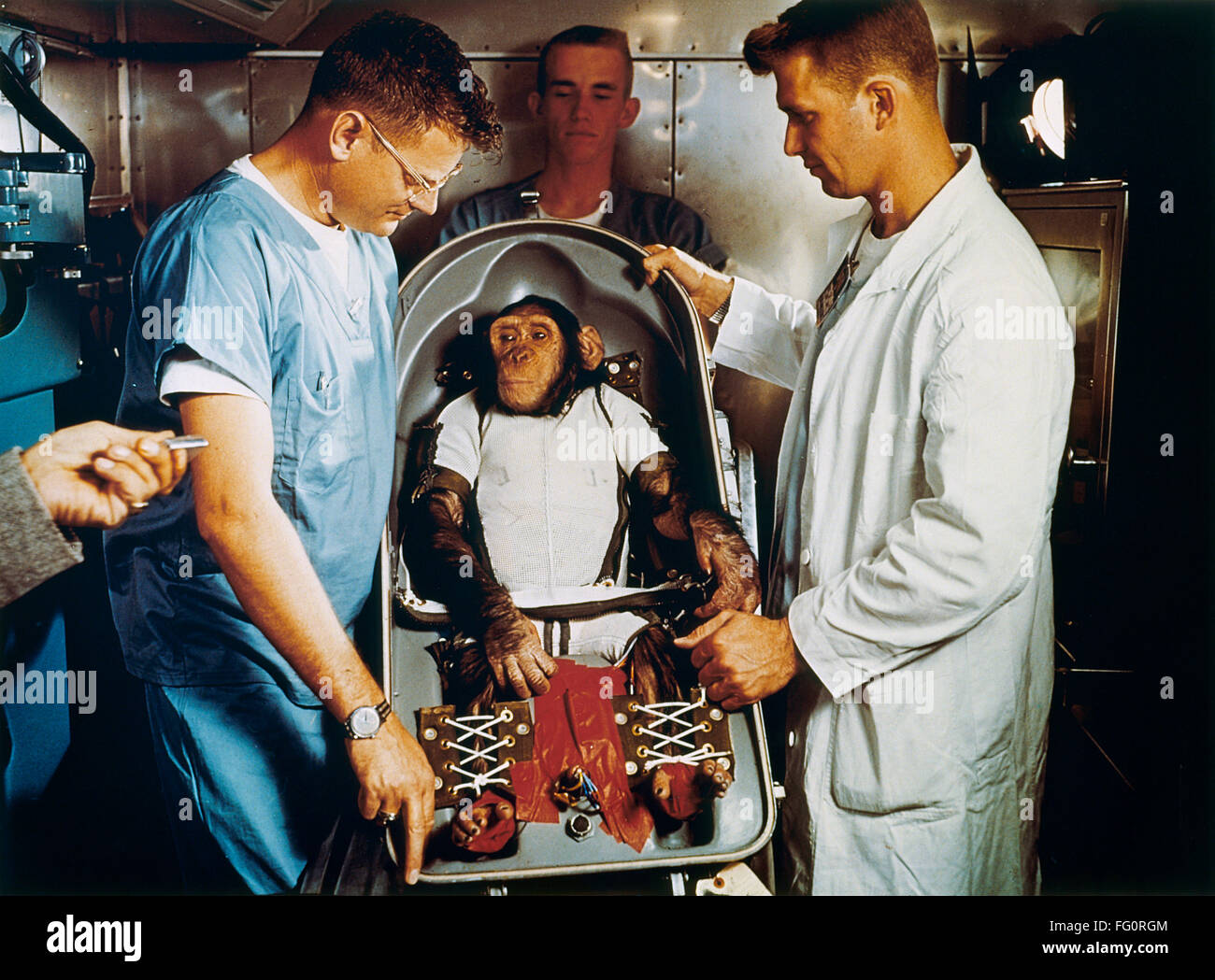

January 31, 1961. A cold morning at Cape Canaveral. While most of America was nursing coffee and worrying about the Cold War, a three-and-a-half-year-old chimpanzee named Ham was being strapped into a pressurized silver canister. He didn't know he was about to become the most famous chimpanzee in space 1961 would ever see. He just knew he’d been trained to pull some levers when a blue light flashed. If he got it right, he got a banana pellet. If he got it wrong, he got a mild shock to the soles of his feet. It was a high-stakes game of Pavlovian conditioning, but the stakes weren't just about fruit or electricity. They were about whether a human being could actually survive the violent physics of leaving Earth.

People often forget how terrifyingly little we knew back then. Some doctors honestly thought a human heart would just stop beating in zero gravity. Others feared the psychomotor skills required to fly a craft would evaporate the moment weightlessness hit. Ham was the "canary in the coal mine," but way faster and much more expensive.

The Mission That Almost Went Horribly Wrong

We like to remember the mission as a flawless success because Ham came back alive, but the actual flight of Mercury-Redstone 2 (MR-2) was a chaotic mess of technical failures. About a minute after launch, things started going sideways. The flight path was about one degree too steep. That doesn't sound like much, right? Wrong. That tiny deviation meant the liquid oxygen was depleted five seconds earlier than planned. The abort system triggered. The escape rocket fired.

Ham wasn't just drifting; he was being hammered.

Instead of the planned 115 miles of altitude, he was flung 157 miles into the sky. He wasn't supposed to go that high. Because the rocket over-performed, the speed reached 5,857 miles per hour instead of the intended 4,400. You've gotta imagine the physical toll on a small primate. At the peak of acceleration, Ham was pulling 14.7 Gs. That is a brutal, rib-crushing amount of pressure. For reference, most fighter pilots start to black out around 9 Gs without specialized suits.

👉 See also: Finding the 24/7 apple support number: What You Need to Know Before Calling

Why Use a Chimpanzee Anyway?

NASA didn't choose chimps because they were cute. They chose them because of the "Great Ape" biological proximity to humans. Their internal organs are arranged similarly. Their nervous systems react to stimuli in ways we can map onto our own. Before Ham, the US had been launching rhesus monkeys and mice, but they couldn't interact with the capsule in a complex way. Ham could.

The task was simple: pull a lever within five seconds of seeing a blue light. During those six minutes of weightlessness, Ham did exactly what he was trained to do. His reaction time was only a fraction of a second slower than it was on the ground. This was the "Eureka" moment for NASA. It proved that a pilot could actually function while falling through a vacuum at thousands of miles per hour. If a chimp could do it under 14 Gs, Alan Shepard could do it too.

The Rescue and the "Smiling" Myth

When the capsule finally splashed down in the Atlantic, it didn't just bob there peacefully. The heat shield had been damaged during the violent reentry, and the capsule began taking on water. By the time the recovery helicopters reached the No. 65 (Ham’s official designation before he was famous), the capsule was tilted dangerously and sinking.

When they finally got him onto the deck of the USS Donner and opened the hatch, the press went wild. There are famous photos of Ham "smiling" at the cameras.

✨ Don't miss: The MOAB Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the Mother of All Bombs

But talk to any primatologist today—like Dr. Jane Goodall or experts from the Lincoln Park Zoo—and they’ll tell you something chilling. That "smile" was actually a "fear grimace." It’s an expression chimpanzees use when they are under extreme stress or feel threatened. Ham wasn't happy to be back; he was terrified. He had spent the last 16 minutes in a metal box, been crushed by G-forces, and almost drowned.

He was eventually offered an apple. He took it. But later, when they tried to put him back in the couch for more photos, he threw a fit. He was done. He wasn’t going back in that box for anyone.

Life After the Stars: The Sad Reality of Research Animals

What happened to the most famous chimpanzee in space 1961 produced? It’s a bit of a bittersweet story.

After his flight, Ham became a celebrity, but you can’t exactly give a chimp a pension and a beach house. He lived at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., for about 17 years. The problem was that he had been raised by humans and then isolated in a high-tech training program. He didn't really know how to "be" a chimpanzee. He was lonely.

🔗 Read more: What Was Invented By Benjamin Franklin: The Truth About His Weirdest Gadgets

In 1980, he was moved to the North Carolina Zoological Park. There, he finally got to live with other chimps, which was probably the first time he felt any sense of normalcy since being captured in French Cameroon as an infant. He died in 1983 at the age of 26. While that sounds old, chimps in captivity can live into their 50s. The stress of his early life likely took a toll.

Key Takeaways from the MR-2 Flight

- Human Flight Validation: Ham’s success directly paved the way for Alan Shepard’s Freedom 7 mission in May 1961.

- Safety Overhauls: The malfunctions during Ham’s flight led to over 50 changes in the Mercury capsule's design to prevent the "over-acceleration" issues.

- Ethical Shifts: The legacy of Ham eventually contributed to the Great Ape Protection Act and the eventual retirement of research chimps by the NIH in 2015.

Understanding the Legacy

We often look at these 1960s missions through a lens of "Space Age" nostalgia, but it’s worth remembering the biological cost. Ham wasn't an astronaut who signed up for the job; he was a forced participant in a geopolitical race. However, without his 16 minutes and 39 seconds of flight, the American space program might have stalled or suffered a fatal accident with its first human pilot.

If you want to pay your respects, you can find Ham’s final resting place at the International Space Hall of Fame in Alamogordo, New Mexico. His skeleton, however, was kept by the National Museum of Health and Medicine for study—a detail that still rubs many the wrong way.

To truly understand this era, you should look into the "Mercury 7" training manuals compared to the "Project Mercury Animal Program" logs. The similarities in their physical conditioning are startling. It highlights just how much NASA viewed the first pilots as biological sensors rather than captains of a ship.

Next Steps for History Buffs:

If you're interested in the technical side of this, look up the "Mercury-Redstone 2 Flight Report." It contains the actual telemetry of Ham’s heart rate and respiration during the flight. For a more human look at the ethics, check out the documentary One Small Step: The Story of the Space Chimps. It digs into the Holloman Air Force Base training colony and what happened to the "backup" chimps who never made it to the launchpad.