It took five years. Leonard Cohen sat in a room at the Royalton Hotel in New York, banging his head against the floor in literal frustration because he couldn't get the verses right. He wrote around 80 of them. Some were notebooks full of religious imagery; others were filthy, carnal, and sweating with desperation. He was a man obsessed. When people hear the song Hallelujah by Leonard Cohen today, they usually think of a soaring, spiritual anthem or a somber movie montage. They don't think about the guy in his underwear crying over a typewriter.

But that’s the reality. It wasn’t a hit. Not even close. When Cohen finally finished the track for his 1984 album Various Positions, the head of Columbia Records, Walter Yetnikoff, looked him in the eye and told him it wasn't any good. They wouldn't even release the album in the United States. Think about that for a second. One of the most covered, most beloved songs in human history was originally deemed "not a hit" by the suits who were supposed to know better. It only survived because it was passed around like a secret among musicians who heard something in it that the radio didn't.

The Biblical Bruises and Broken Chords

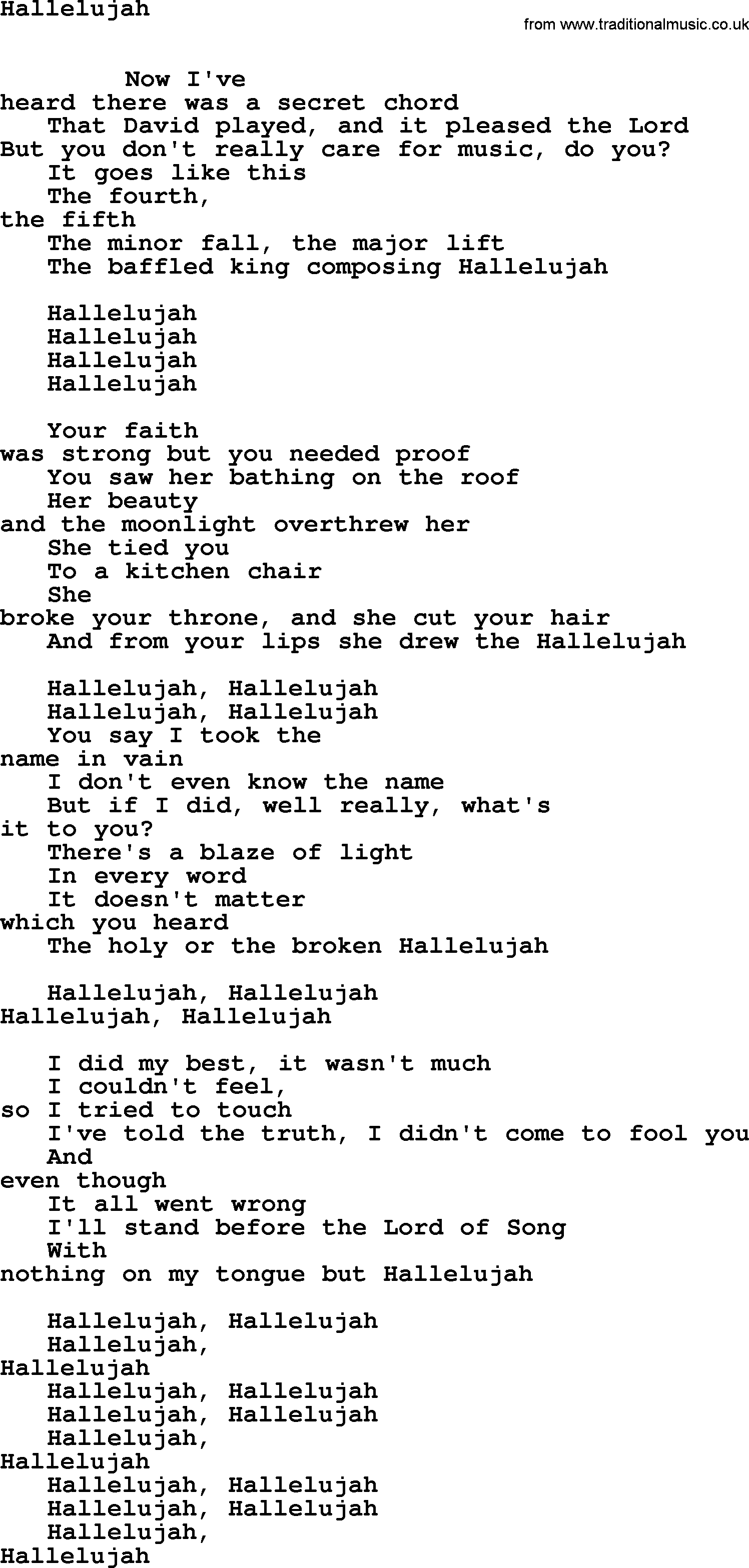

The genius of the song Hallelujah by Leonard Cohen lies in its duality. It isn't a church hymn, though it uses the language of the Old Testament. It’s a song about the failure of love and the endurance of the spirit. Cohen weaves together the story of King David—the "baffled king" composing the sacred chord—with the story of Samson and Delilah. "She cut your hair," he writes, referencing the loss of strength and the betrayal of intimacy.

It’s messy.

Most pop songs pick a lane. They’re either happy or they’re sad. Cohen refused to choose. He argued that "Hallelujah" is a word that should be uttered even when things are falling apart. It’s a "cold and broken" hallelujah. This nuance is why the song feels so heavy. When you hear that opening C major to F major progression—the "fourth, the fifth"—you aren't just hearing music; you're hearing a technical description of the song's own construction. Cohen is literally telling you what the music is doing while it’s doing it. The minor fall, the major lift. It’s a meta-commentary on the struggle of creation itself.

✨ Don't miss: Bob Hearts Abishola Season 4 Explained: The Move That Changed Everything

Honestly, the song is a bit of a miracle. It survived because John Cale (of The Velvet Underground) saw its potential. In 1991, Cale requested the lyrics from Cohen to record a cover for a tribute album. Cohen faxed him fifteen pages of verses. Cale had to sift through the pile, discarding the overtly religious bits and focusing on the "cheeky" and secular ones. This became the blueprint. If Cale hadn't edited Cohen’s sprawling poem into a tighter structure, we might never have gotten the Jeff Buckley version. And without Buckley, the song might have stayed a niche folk track.

The Jeff Buckley Effect

Buckley heard Cale's version while staying at a friend’s apartment. He didn't even know the original Cohen recording. When Buckley recorded it for his 1994 album Grace, he turned it into something fragile and erotic. It became a ghostly masterpiece. It’s the version that launched a thousand covers. But it’s also the version that started the "American Idol-ification" of the track. Suddenly, everyone wanted to sing it. It showed up in Shrek. It showed up at weddings. It showed up at funerals.

This ubiquity is a double-edged sword. Cohen himself once joked in an interview with the CBC that he thought people should stop singing it for a while. He felt the song had been overused. And he was right. When a song becomes a cliché, we stop listening to the words. We forget that the song Hallelujah by Leonard Cohen is actually quite dark. It’s about a relationship that’s "not a victory march." It’s a "holy or a broken Hallelujah."

Why the Song Hallelujah by Leonard Cohen Still Breaks Us

Why does it still work? Because it’s honest about failure. In a world of over-polished pop stars and Instagram filters, Cohen’s lyrics admit that we don't always get what we want. "I've told the truth, I didn't come to fool you." That line hits because most art is trying to fool us. It’s trying to sell us a version of life that is cleaner than the one we actually live.

🔗 Read more: Black Bear by Andrew Belle: Why This Song Still Hits So Hard

Cohen spent his life exploring the intersection of the divine and the dirty. He was a Zen monk who liked expensive suits and cognac. He was a poet who understood that the only way to find the light is to acknowledge the crack in everything. That’s where the light gets in, as he famously wrote in "Anthem." But in "Hallelujah," the light is a little more flicker-y. It’s the light of a room where someone just left.

- The "Secret Chord": People often ask if the "secret chord" is real. Musically, the song follows a 12/8 time signature, which gives it that rolling, gospel feel. The "fourth, the fifth / the minor fall, the major lift" refers to the F major, G major, A minor, and F major chords. It’s a standard progression, but Cohen makes it feel like an ancient mystery.

- The Versions: There are over 300 known covers. Rufus Wainwright, k.d. lang, Brandi Carlile, Bon Jovi, Pentatonix. Everyone tries to claim it. k.d. lang’s version is perhaps the most technically perfect, but Buckley’s remains the most emotionally raw.

- The Evolution: Cohen changed the lyrics constantly. If you listen to his live recordings from the 80s versus his "Grand Tour" recordings in the 2000s, the song shifts. It grows older with him. It becomes less about the bedroom and more about the finish line.

A Masterclass in Persistence

There is a lesson here for anyone who creates anything. Cohen didn't give up on the song when his label rejected it. He didn't give up when it took five years to write. He understood that some things take time to ripen. The song Hallelujah by Leonard Cohen is a testament to the "long game." In our current culture of instant gratification and viral TikTok hits, there’s something deeply comforting about a song that took decades to reach its peak. It didn't go viral. It permeated the culture through sheer quality and the endorsement of other artists.

It’s also a reminder that the creator doesn't always have the final say on what a work means. Cohen’s original version was synth-heavy and a bit "80s-sounding." It lacked the intimacy we now associate with the track. It took other voices to find the heart of his poem. That’s a beautiful thing. It’s a collaboration across time and space.

Moving Beyond the Clichés

To truly appreciate the song Hallelujah by Leonard Cohen, you have to strip away the baggage. Forget the TV talent shows where singers over-sing every syllable. Go back to the text. Read it as a poem first. Notice the bitterness in lines like "All I ever learned from love / Was how to shoot at someone who outdrew you." That’s not a greeting card sentiment. That’s a wound.

💡 You might also like: Billie Eilish Therefore I Am Explained: The Philosophy Behind the Mall Raid

If you want to experience the song properly, do these three things:

- Listen to the John Cale version. It’s on the I'm Your Fan tribute album. It’s the bridge between Cohen’s grit and Buckley’s grace. It features just a piano and a voice, and it’s arguably the most "honest" version of the structure we know today.

- Read the full "lost" verses. Look for the lyrics Cohen wrote that didn't make the standard radio edit. They offer a much darker, more complex look at the themes of sexuality and religious ecstasy.

- Watch the 2022 documentary, Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song. It tracks the specific trajectory of the song’s life, from the rejection at Columbia to the global phenomenon it is now. It features archival footage that shows just how much Cohen wrestled with these words.

The song isn't a funeral dirge or a celebration. It’s a middle ground. It’s the sound of someone admitting they don't have all the answers, but they're going to keep singing anyway. That is the most human thing there is. We are all just "baffled kings" trying to find the right notes in a world that doesn't always want to hear them. And maybe that's enough.

The real power of Cohen's work wasn't in the perfection of the "secret chord," but in the willingness to keep looking for it. Even when the room was cold. Even when the hair was cut. Even when the hallelujah felt broken. He kept writing. He kept singing. And eventually, the rest of the world caught up.

To dive deeper into the technical side of his songwriting, start by analyzing the 12/8 time signature used in the original recording. It’s the "heartbeat" of the track and explains why the song feels so much like a slow-motion dance. From there, compare the 1984 studio version with the Live in London (2009) performance to see how Cohen’s own relationship with the song aged over twenty-five years.