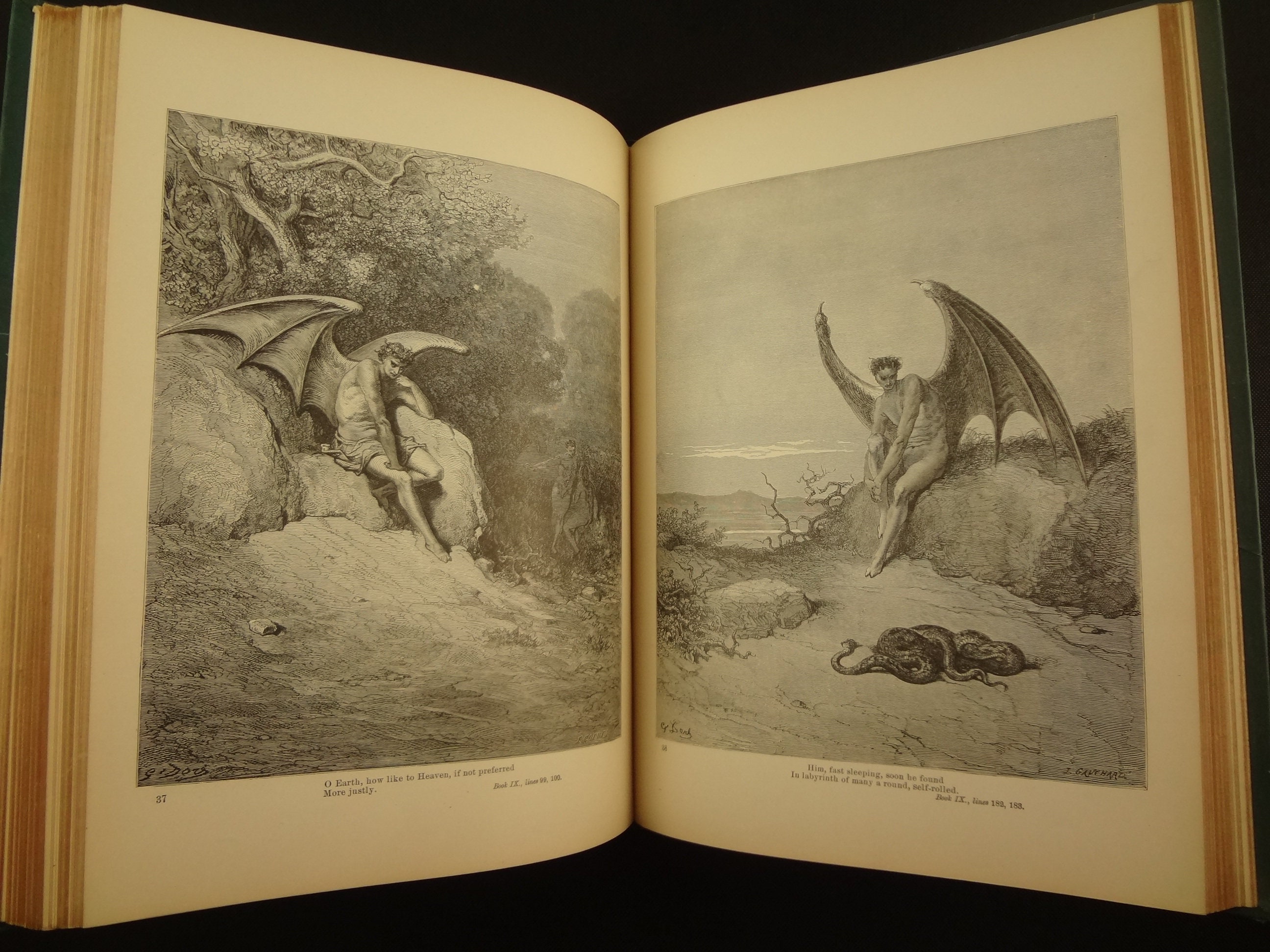

When you think of the Devil, you probably see a specific image in your head. Dark wings. A brooding, muscular physique. Maybe a look of profound, agonizing regret. Honestly, you probably have Gustave Doré Paradise Lost illustrations to thank for that. His 1866 wood engravings didn't just decorate John Milton’s epic poem; they basically hijacked our collective imagination. Before Doré, Satan was often just a grotesque monster. After Doré, he became the tragic, "bad boy" anti-hero we see in modern movies and comics.

People love these drawings. They’ve been shared, tattooed, and turned into heavy metal album covers for over 150 years. But there’s a lot of weird stuff about how they were actually made that most folks just don’t realize.

👉 See also: Jimmy Fallon Paul Rudd Lip Sync: Why This 2014 Moment Is Still The Gold Standard

The Weird Reality of the Gustave Doré Paradise Lost Engravings

First off, let’s talk about the sheer scale of the project. Doré didn't just sit down and sketch a few pictures. He produced 50 massive plates for the original edition. This wasn't some indie passion project. It was a high-stakes commercial gamble.

The publisher, Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, actually approached Doré because they were so blown away by his work on the Bible. They wanted something "grand." They got it. But here is the kicker: Doré didn't actually carve the wood himself.

Most people assume he was some lone genius with a tiny chisel.

Nope.

✨ Don't miss: Why Tonight Lyrics We Are Young Still Hits Hard Fourteen Years Later

He was more like a movie director. He would sketch the incredibly detailed designs directly onto blocks of boxwood, often painting the wood white first to see his lines better. Then, he’d hand those blocks over to a small army of professional engravers—guys like Héliodore Pisan. If you look at the bottom of a Gustave Doré Paradise Lost print, you’ll usually see two names. Doré on the left, and the engraver on the right.

It was a factory of high art.

Why His Version of Satan Is So Famous

The way Doré handled Milton’s Satan is probably his biggest contribution to pop culture. In the poem, Milton describes Satan as a "Fallen Angel," and Doré took that literally. He gave him human-like features and vast, leathery wings.

It’s about the lighting.

👉 See also: Why Jingle Bell Jingle Bell Jingle Bell Rock Lyrics Still Rule the Holidays

Doré was the master of chiaroscuro—that fancy word for high-contrast light and shadow. Look at the plate where Satan is rallying his fallen troops in Hell. The way the light hits his shoulders makes him look more like a tragic king than a demon. It’s why Ray Harryhausen, the legendary stop-motion animator, once called Doré a "motion-picture art director born before his time." He knew how to frame a shot.

The Technical Madness of 19th-Century Wood Engraving

You’ve got to understand how hard this was. Wood engraving uses the end-grain of the wood. It’s harder than a normal woodcut, which uses the side of a board. This allowed for lines so thin they looked like hair.

Imagine trying to "draw" with a sharp metal tool by scratching white lines into a black surface. You can't undo a mistake. One slip of the wrist, and a month of work is ruined. Because the blocks of boxwood were small, for a large Gustave Doré Paradise Lost plate, several blocks would be bolted together.

Sometimes, for rush jobs, the blocks were unscrewed and given to different engravers to work on different parts of the same image at once. Talk about teamwork.

What People Miss About Adam and Eve

While everyone obsesses over the demons, Doré's depiction of Eden is equally wild. He went for this "Romantic" style—big, sweeping landscapes where the humans look tiny. It makes the world feel ancient and overwhelming.

When Adam and Eve are finally kicked out of Paradise, Doré doesn't focus on their faces as much as he focuses on the vast, lonely world they’re walking into. It’s a gut-punch of an image. You feel the scale of their loss.

Why It Still Matters in 2026

You see his influence everywhere. From the aesthetic of The Lord of the Rings to the way George Lucas framed shots in Star Wars, the DNA of Gustave Doré Paradise Lost is in there. He created the visual language for "Epic."

If you're a collector or just a fan, here’s what you actually need to know if you're looking for these today:

- Check the signatures: Real 19th-century prints will always have the engraver's name (like Pisan) alongside Doré's.

- The 1866 Edition: This is the "holy grail" for collectors. Later reprints often lost the crispness of the lines because the wood blocks wore down over time.

- Digital Archives: You don't have to spend thousands. Places like the Internet Archive and the British Museum have high-res scans where you can see every single tiny scratch of the engraver's tool.

Honestly, the best way to experience his work isn't on a phone screen. If you ever get the chance to see a physical 1866 folio edition, do it. The sheer size of the book makes you feel small. It was designed to be a physical experience, a heavy, leather-bound door into another world.

If you want to start a collection or just get a decent print for your wall, look for "Dover Publications" reprints. They’ve done a solid job of preserving the detail without the "rare book" price tag. Or, dive into the digitized collections at the Musée d’Orsay to see how his sketches differ from the final engravings. Just don't be surprised if you start seeing his influence in every movie you watch from now on.

Next, you might want to look into how Doré's Divine Comedy illustrations actually set the template for his work on Milton. It’s a bit of a prequel to his style in Paradise Lost. Or, check out the original 1866 Robert Vaughan edition to see the text and art together as they were meant to be seen.