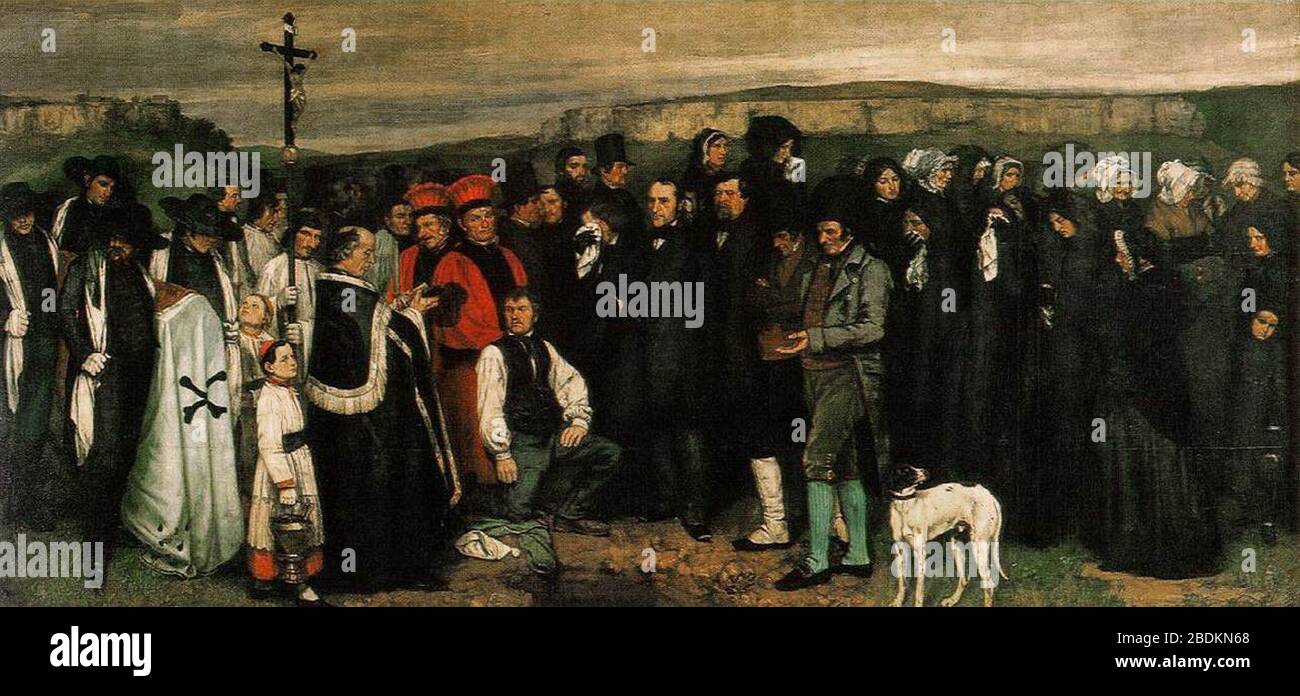

It is huge. Seriously, if you stand in front of Gustave Courbet A Burial at Ornans at the Musée d'Orsay, the first thing that hits you isn't the gloomy color palette or the weeping women; it’s the sheer, aggressive scale of the thing. We are talking about a canvas that is roughly 10 feet tall and 22 feet wide. In 1850, size like that was reserved for kings, gods, and epic battles.

Then Courbet used it to paint a hole in the ground.

He didn't give us a heroic death scene. He didn't paint a saint ascending to heaven with glowing cherubs. He just painted a bunch of middle-class country folk standing around a grave in a muddy field in provincial France. At the time, the Parisian art elite absolutely hated it. They called it "the burial of Romanticism." They thought it was ugly, vulgar, and—worst of all—pointless. But that was exactly what Courbet wanted. He wasn't trying to be pretty. He was trying to be real.

The Scandal of the Ordinary

Why did a painting of a funeral cause a literal riot in the art world? To understand that, you've gotta understand the rules of the Paris Salon back then. If you wanted to be taken seriously, you painted "History Painting." You painted Napoleon. You painted Venus. You painted something that made people feel noble.

Courbet did the opposite.

He took the grandest possible format and filled it with "nobodies." These weren't models; they were his neighbors, his family, and the actual townspeople of Ornans. When Gustave Courbet A Burial at Ornans debuted at the 1850–1851 Salon, critics were baffled. Why are these people so... plain? Why is that dog just sitting there? Why is the hole for the coffin cut off at the bottom of the frame, making the viewer feel like they’re about to fall into the dirt?

✨ Don't miss: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

The painting didn't have a "hero." There is no central figure basking in light. Instead, Courbet gives us a line of people that stretches across the canvas like a frieze. It’s democratic. It’s flat. It’s brutally honest. Honestly, it was a political statement disguised as a landscape. By giving rural peasants the same visual importance as emperors, Courbet was basically sticking his thumb in the eye of the Parisian establishment.

Realism vs. The Pretty Lie

Courbet is often called the father of Realism. He famously said, "Show me an angel and I'll paint one." Since he hadn't seen any angels, he stuck to what he knew: the damp, grey reality of the Franche-Comté region.

In A Burial at Ornans, you see the red-faced beadles (the church officials) who look like they might have had a bit too much wine before the ceremony. You see the tired faces of the veterans from the 1793 revolution. You see the distraction. Look closely at the mourners. Some are crying, sure, but others look bored. Some are looking away. This is how grief actually works. It’s messy, it’s distracting, and it’s often very quiet.

The art world at the time called this "the cult of the ugly." They couldn't wrap their heads around the fact that Courbet wasn't trying to "elevate" the subject. He was just reporting it. He used a palette knife to slap on thick layers of paint, giving the rocks and the clothes a physical, heavy texture. It felt raw. It felt unwashed.

Who Are These People Anyway?

Courbet didn't just guess what a funeral looked like. He invited the people of his hometown into his studio to pose. Imagine the scene: a small-town studio packed with the mayor, the local priest, and the town drunk, all waiting for their turn to be immortalized on a canvas meant for the Louvre.

🔗 Read more: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

- The Deceased: It’s widely believed the funeral was for Courbet's grand-uncle, Claude-Étienne Testot, who died in 1848.

- The Clergy: The priest is there, reading from his book, but he doesn't seem particularly holy. He’s just doing his job.

- The Mourners: His sisters, Zoé, Zélie, and Juliette, are the weeping women in black. His father is there too.

- The Dog: That white and black dog in the foreground? Critics hated it. They thought it was "distracting." But for Courbet, the dog was part of the truth. Dogs show up at burials. Life goes on around death.

By using real people, Courbet bypassed the "idealized" faces common in art. These are weathered, wrinkly, tan-lined faces. It’s a snapshot of a community, captured with a level of detail that felt almost like a photograph before photography was a mainstream thing.

The Composition That Broke the Rules

Usually, a painting tells you where to look. There’s a "V" shape or a circle that draws your eye to the most important bit. Courbet doesn't do that. A Burial at Ornans is notoriously "additive." It’s just one person after another.

This lack of a focal point was a huge deal. It suggested that no one person in the town was more important than the other. Even the crucifix, held high by an altar boy, is pushed off to the side and blends into the background. Some interpreted this as Courbet’s way of saying that the church was losing its grip on the people, or at least that it was just another part of the scenery rather than the center of the universe.

The horizon line is high. The sky is a narrow strip of gloomy grey. This creates a feeling of claustrophobia. You are trapped in the valley with these people. You are trapped with the reality of the grave.

The Political Undercurrents

You can't talk about Gustave Courbet A Burial at Ornans without talking about the year 1848. Europe was on fire. Revolutions were popping up everywhere. The working class was demanding a voice.

💡 You might also like: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

When Courbet brought this painting to Paris, the bourgeoisie saw it as a threat. To them, these weren't just "peasants." They were the "vile multitude"—the people who might rise up and take their property. By painting them on a massive scale, Courbet was saying: "These people exist. They have dignity. And they aren't going anywhere."

He was a socialist, and he didn't hide it. He was a friend of the philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. For Courbet, art was a weapon. He used it to dismantle the idea that only the elite deserved to be the subject of "High Art."

Why It Still Matters Today

In a world of Instagram filters and AI-generated perfection, Courbet’s "Realism" feels surprisingly modern. We are still arguing about what is "worthy" of being documented. We still struggle with the idea of finding beauty in the mundane or the "ugly."

Courbet taught us that the ordinary is extraordinary. He showed that a small-town funeral is just as epic as a Napoleonic war if you look at it with enough honesty. He paved the way for Impressionism, for Modernism, and for every artist who ever decided to paint the world exactly as they saw it, rather than how the "experts" told them it should look.

The painting remains a cornerstone of the Musée d'Orsay collection because it is uncomfortable. It doesn't offer a hug. It offers a cold, hard look at a hole in the ground and the people standing around it. And in that coldness, there is a weird kind of comfort—the comfort of knowing that your life, as ordinary as it might be, is worth 22 feet of canvas.

Actionable Insights for Art Lovers

If you're looking to truly appreciate or study Gustave Courbet A Burial at Ornans, don't just look at a digital thumbnail. It doesn't work.

- Check the Scale: If you can’t get to Paris, find a "scale comparison" online. Understanding that the figures are nearly life-sized changes your perspective on the "confrontational" nature of the work.

- Look at the Paint, Not the Picture: Zoom in on high-resolution scans. Notice the "impasto"—the thick, chunky application of paint. Courbet used a palette knife for much of this, which was radical. It makes the earth look like real dirt.

- Contrast with the Classics: Open a tab with a painting by Jacques-Louis David or Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Look at how they paint skin (smooth, like marble) versus how Courbet paints it (leathery, blotchy). It highlights exactly why Courbet was such a rebel.

- Research the "Ornans Cycle": This wasn't a one-off. Courbet did a series of paintings about his hometown, including The Stonebreakers (which was sadly destroyed in WWII). Seeing them as a set helps you understand his mission to document the French countryside.

- Visit the Musée d'Orsay: If you ever go, don't just stand in front of the painting. Walk from one end to the other. Notice how the "parade" of mourners seems to move with you. It’s an immersive experience that no book can fully replicate.

Courbet didn't want to please you. He wanted to wake you up. Whether you love the painting or find it depressing, the fact that we’re still talking about it 175 years later means he definitely won the argument.