Westerns usually follow a script you can set your watch to. The lone rider. The dusty town. The inevitable showdown at high noon. But then there is Guns for San Sebastian—or La Bataille de San Sebastian if you’re feeling fancy—and it sort of throws the whole playbook out the window. Released in 1968, this film isn't just another notch in Anthony Quinn’s belt; it’s a weird, sweaty, sprawling epic that feels more like a fever dream than a traditional shootout flick.

Honestly, if you haven’t seen it lately, you're missing out on one of the most chaotic productions of the late sixties. We are talking about a movie filmed in Mexico, directed by a Frenchman (Henri Verneuil), starring a Mexican-American icon, and scored by an Italian legend. It’s a mess on paper. On screen? It’s kind of brilliant.

The plot kicks off with Alastray, played by Quinn, who is a rebel on the run from the Spanish army. He ends up in the village of San Sebastian, disguised as a priest. The locals, who have been absolutely terrorized by Yaqui rebels, think he’s their savior. Not the spiritual kind—the kind that knows how to lead a militia. It’s a classic "mistaken identity" trope turned into a gritty survival story.

The Reality of Guns for San Sebastian and the 1960s Western Boom

Back in '68, the Western was undergoing a massive identity crisis. The squeaky-clean John Wayne era was dying out. Sam Peckinpah was busy making everything bloodier. Over in Italy, Sergio Leone was making everyone look cool in ponchos. Guns for San Sebastian sits in this strange middle ground. It has the grand scale of a Hollywood production but the cynical, dusty soul of a Spaghetti Western.

People often forget how big of a deal this was for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). They poured money into it. They got Ennio Morricone to do the score. If you know anything about cinema, you know that a Morricone score is basically a cheat code for "iconic status." His work here is haunting. It’s not the playful whistling of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. It’s choral. It’s heavy. It feels like the weight of God is pressing down on the characters.

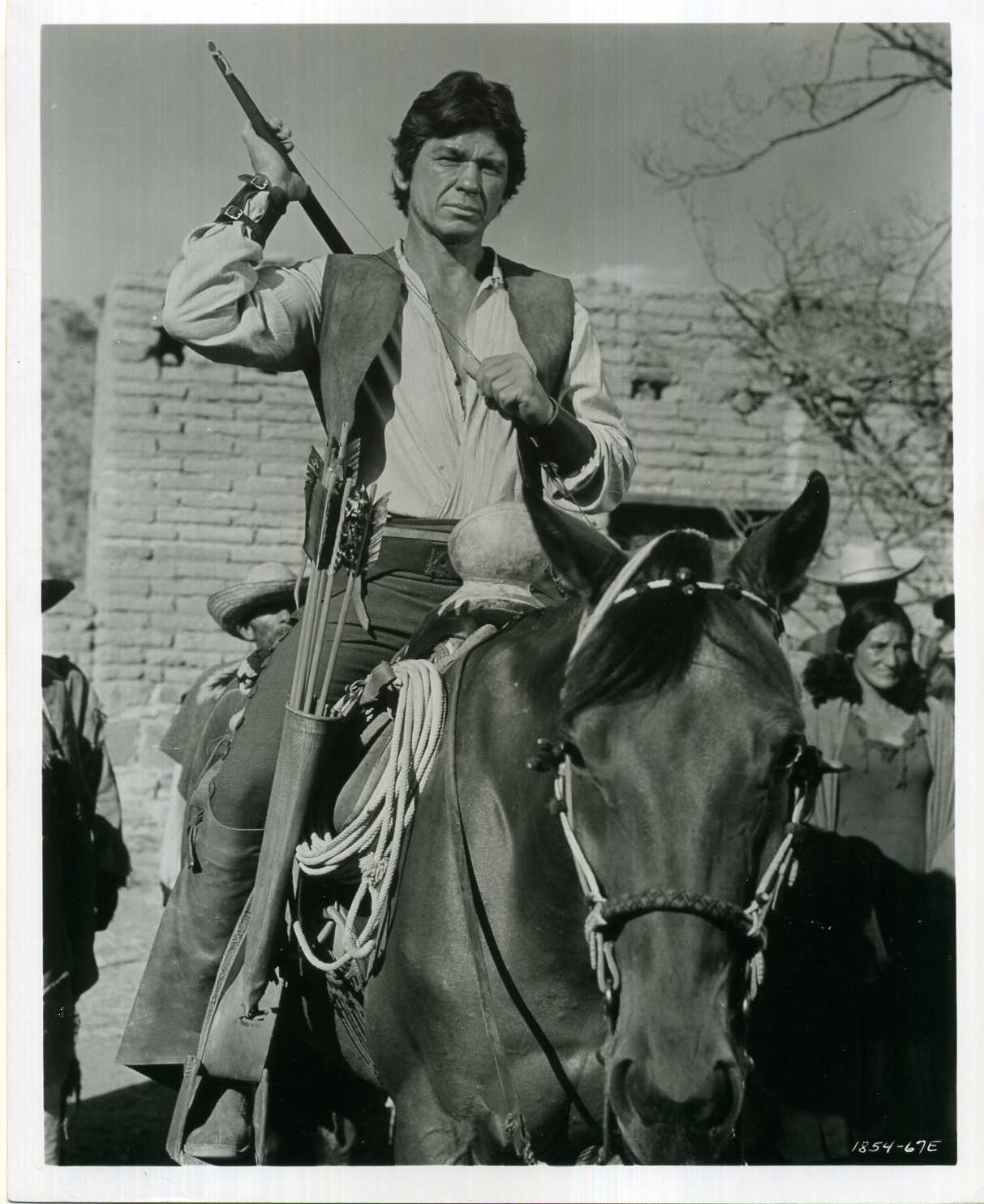

Shooting in Mexico wasn't just a cost-saving measure; it was essential for the vibe. The harsh sunlight makes the actors look permanently exhausted. Charles Bronson shows up as Teclo, the half-breed antagonist who wants the villagers to stay scared so he can keep his power. Bronson is, well, Bronson. He doesn't need to say much. He just stares at the camera with those squinty eyes and you know someone is about to get hurt.

Why the "Priest with a Gun" Trope Worked

There’s something inherently cool about a character who shouldn't be fighting but has to. Alastray isn't a holy man. He’s a sinner. A fugitive. Yet, the villagers’ faith in him forces him to become the man they think he is. It’s a fascinating psychological pivot.

Most Westerns focus on the "how" of the gunfight. This one focuses on the "why."

💡 You might also like: Why Bullet with Butterfly Wings Lyrics Still Define 90s Angst

The villagers are pacifists or just broken people. Alastray has to teach them to build a dam, to farm, and eventually, to kill. It’s a dark transition. There is a specific scene where the villagers realize their "priest" is a fraud, yet they don’t care. They need a general more than a preacher. That’s a heavy concept for a movie made over fifty years ago.

Technical Brilliance and the Morricone Factor

You can't talk about this movie without talking about the sound. Seriously.

- The wind. It’s a character in itself.

- The lack of dialogue in key sequences.

- That soaring, religious-themed score.

Henri Verneuil wasn't a Western specialist. He was known for French crime capers like The Sicilian Clan. This gave the movie a different visual language. The camera stays wide. It captures the desolation of the Mexican plateau. It makes the village of San Sebastian feel like it’s at the very edge of the world.

And then there’s the action. The final siege is massive. It doesn't feel choreographed like a modern Marvel movie. It feels like a riot. It’s messy. People fall over things. Explosions happen too close to the actors. It has a tactile reality that CGI just can't replicate. You can almost smell the gunpowder and the horse sweat.

The Casting Dynamics: Quinn vs. Bronson

Anthony Quinn was in his prime here. He had this incredible ability to look both incredibly strong and completely vulnerable at the same time. He plays Alastray with a sort of frantic energy.

Then you have Charles Bronson. At this point, Bronson was on the verge of becoming the biggest star in the world. He had just done The Dirty Dozen and was about to do Once Upon a Time in the West. In Guns for San Sebastian, he plays a villain, but he’s a nuanced one. He’s not a cartoon. He’s a man who understands power dynamics. He knows that if the villagers gain hope, his influence vanishes. It’s a battle of ideologies as much as it is a battle of bullets.

Historical Accuracy vs. Cinematic Flair

Let's be real: Guns for San Sebastian is not a documentary. It takes place in 1746, a period not often covered by the typical "cowboy" movie. The conflict between the Spanish authorities, the church, and the indigenous tribes is simplified for the sake of drama.

The Yaqui people were real, and their resistance against Spanish and later Mexican rule is a deep, often tragic part of history. The film uses them mostly as a looming threat—a force of nature. It’s a very "1960s Hollywood" way of handling indigenous history. While the film doesn't dive deep into the complexities of Yaqui culture, it does acknowledge the brutal reality of frontier life where everyone was fighting for a piece of land that probably didn't want them there in the first place.

Common Misconceptions About the Film

A lot of people think this is a sequel or a spin-off of other Quinn movies because he played so many "tough guys in the desert." It’s a standalone story based on the novel A Wall for San Sebastian by William Barnaby Faherty.

Another mistake? Thinking it’s a Spaghetti Western. It’s not. It’s a French-Italian-Mexican co-production. While it shares some DNA with the Italian style, it’s much more operatic. It’s grander. It lacks the tongue-in-cheek humor of the Leone films. This is a dead-serious movie about survival and the loss of innocence.

The Lasting Legacy of San Sebastian

Why do we still talk about this movie? Why does it show up on Turner Classic Movies or in the collections of Quentin Tarantino fans?

Because it’s brave.

It tackles the hypocrisy of organized religion. It shows a hero who is fundamentally a liar. It ends on a note that isn't exactly "happily ever after." Alastray saves the town, but he can't stay. He’s still a man with a price on his head. The cycle of violence continues.

The film also influenced a generation of filmmakers who wanted to break away from the "White Hat vs. Black Hat" dynamic. It proved that you could have a massive budget and still tell a story that felt dirty, uncomfortable, and real.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Collectors

If you're looking to dive into the world of Guns for San Sebastian, don't just stream it on a low-res site. The cinematography by Armand Thirard is too good for that.

- Seek out the Blu-ray: The 2017 Warner Archive release is the gold standard. It cleans up the grain without losing the "film" feel. The colors of the Mexican landscape pop in a way that old DVD transfers just couldn't handle.

- Listen to the Soundtrack separately: Ennio Morricone’s score is widely considered one of his "hidden gems." It’s available on vinyl and digital. It’s great background music for when you need to feel like you’re defending a village from marauders.

- Contextualize the Era: Watch it as a double feature with The Wild Bunch. You’ll see how 1968-1969 was the turning point where the Western became "adult" once and for all.

- Look for the nuance: Pay attention to the character of Sam (Anjanette Comer). She isn't just a damsel in distress; she’s the one who actually holds the village's moral compass while the men are busy shooting at each other.

The movie isn't perfect. Some of the pacing in the middle drags. Some of the supporting performances are a bit wooden. But the highs? The highs are soaring. When the dam breaks, or when Quinn finally picks up a rifle to defend people he doesn't even know, it’s pure cinema.

If you want to understand where the modern "gritty" action movie came from, you have to look at films like this. It took the tropes of the past and dragged them through the mud. It made the hero bleed. It made the choices matter. Guns for San Sebastian remains a testament to a time when movies were allowed to be big, weird, and deeply cynical all at once.

Grab some popcorn, turn up the speakers for Morricone, and watch Anthony Quinn become a legend. Again.