You’ve likely felt it. That weird, heavy tension in a conference room where nobody wants to speak first. Or maybe you've been part of a "dream team" that, for some reason, just couldn't stop tripping over its own feet. It’s frustrating. It’s also exactly why understanding the group dynamics meaning matters more than the actual skills on a resume.

People aren't Lego bricks. You can't just snap them together and expect a sturdy house.

The Core Concept: What are we actually talking about?

At its simplest level, the term refers to the invisible forces—the "psychological weather"—that happen when two or more people interact. It's how we influence each other, how we compete for status, and how we decide who gets to lead without ever saying a word. Social psychologist Kurt Lewin coined the term back in the 1940s. He basically argued that it’s easier to change the behavior of an entire group than it is to change the behavior of a single individual in isolation. Think about that for a second. The group is its own living, breathing organism.

It isn't just "teamwork." Teamwork is the output. Group dynamics are the plumbing.

If the pipes are rusted or the pressure is too high, the whole thing bursts. We see this in everything from high-stakes surgical teams to a group of friends trying to decide where to go for dinner. There's a push and pull. There are roles—some obvious, some subtle. You have the "harmonizer" who tries to keep everyone happy, and the "blocker" who shoots down every idea because they’re afraid of change.

Why social identity theory changes the game

To really get what is the meaning of group dynamics, you have to look at how we see ourselves. Henri Tajfel’s Social Identity Theory explains that we naturally divide the world into "us" and "them."

Inside a group, this creates an "in-group" bias. It makes us feel safe, but it also makes us stupidly competitive with other departments. If the marketing team thinks the sales team is "the enemy," your company's internal dynamics are basically a civil war. This isn't just a business problem; it's a fundamental human hardwiring issue. We want to belong, but belonging often requires having an outsider to exclude.

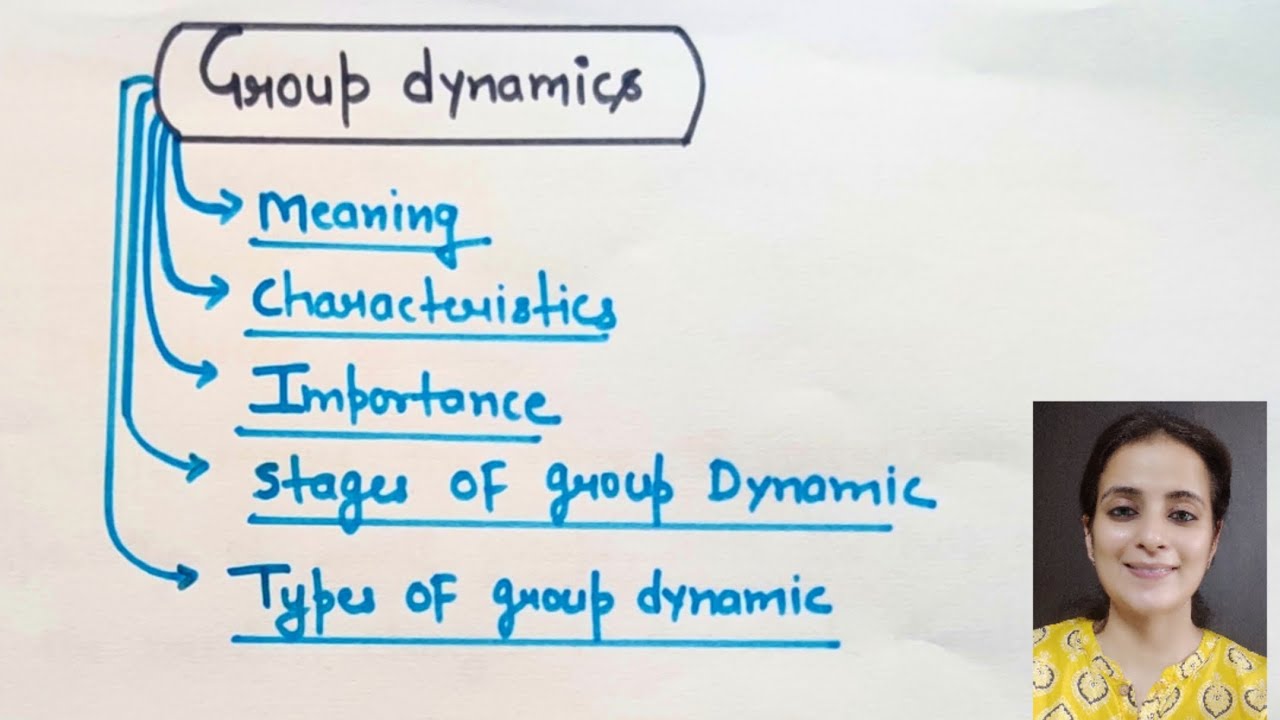

The Five Stages of Group Development (The Tuckman Model)

Bruce Tuckman laid this out in 1965, and honestly, it’s still the gold standard for a reason. Most people think groups just "start" and then "do work." They don't.

First, there’s Forming. This is the "polite" stage. Everyone is on their best behavior, sniffing each other out like dogs at a park. You’re trying to figure out what the rules are. Nobody is being honest yet.

💡 You might also like: What Is a Byproduct? Why Most People Get the Definition Wrong

Then comes Storming. This is where the wheels usually fall off.

People start pushing boundaries. They challenge the leader. They argue over how things should be done. If you’ve ever been in a meeting that felt like an episode of Survivor, you were in the storming phase. A lot of groups never actually make it past this. They just stay in a state of low-level, passive-aggressive conflict forever. It’s exhausting.

Moving into the "sweet spot"

If you survive the storming, you hit Norming. This is where people start to actually like each other—or at least respect each other. You develop a "shorthand." Rules are established. People know that Dave always brings the coffee and Sarah always plays devil’s advocate, and they’re okay with it.

Finally, you reach Performing. This is the flow state. The group is firing on all cylinders. You don't have to explain everything because everyone is in sync. It’s rare. It’s beautiful. It’s also temporary.

Eventually, there’s Adjourning. The project ends. People move on. There’s a sense of loss here that managers often ignore. If you don't acknowledge the end of a group, the people in it might struggle to fully engage with their next team.

The Dark Side: Groupthink and Deindividuation

Group dynamics aren't always positive. Sometimes, they're terrifying.

Have you heard of Groupthink? Irving Janis came up with this after looking at huge political blunders like the Bay of Pigs. It happens when the desire for harmony is so strong that nobody speaks up against a bad idea. Everyone assumes everyone else agrees, so they stay silent. It’s a collective hallucination of competence.

Then there’s Deindividuation. This is when you lose your sense of self within a group. You do things as part of a crowd that you would never, ever do alone. It’s the psychology behind riots, but also behind toxic office cultures where "this is just how we do things here" becomes an excuse for bullying or unethical behavior.

🔗 Read more: GM Factory Zero Shift Shutdown: Why the Hummer EV Line is Going Quiet

- The Bystander Effect: The more people there are, the less likely anyone is to help.

- Social Loafing: People tend to put in less effort when they're in a group because they think they can hide.

- The Ringelmann Effect: Max Ringelmann found that in a tug-of-war, the more people on the rope, the less hard each individual pulled.

Factors That Actually Influence the Dynamic

Size matters. A group of three is fundamentally different from a group of twelve. In a group of three, there's nowhere to hide. In a group of twelve, you start to see "sub-groups" or cliques forming. These cliques can be poisonous. They create an "inner circle" that makes everyone else feel like an outsider.

Diversity is another big one. Not just the kind you see on a corporate brochure, but cognitive diversity. If everyone thinks the same way, the group is fast but brittle. You’ll make decisions quickly, but you’ll miss the giant iceberg right in front of you. If the group is diverse, it’ll be slower and more frustrating, but the end result is usually much more robust.

The role of psychological safety

Amy Edmondson at Harvard basically changed the way we look at teams with this one. Psychological safety is the belief that you won't be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes.

In a group with high psychological safety, the dynamics are fluid. People take risks. In a group with low safety, everyone is just protecting their own neck. It doesn't matter how smart the individuals are; if the dynamic is fear-based, the output will be mediocre.

How to Read the Room: Real-World Examples

Look at the seats. In a meeting, who sits next to the boss? Who sits by the door? These aren't accidents. They are physical manifestations of the group dynamics meaning.

I once saw a tech startup where the CEO sat at a circular table in the middle of the room. He thought he was being "flat" and "approachable." But because he was still the one with the power to fire people, his presence in the middle actually stifled conversation. People were literally afraid to turn their backs on him to talk to each other. The "dynamic" was one of constant surveillance, even though he meant well.

Contrast that with a high-performing jazz band. There is a clear leader, but the dynamic allows for "solo" moments where the leader steps back and follows. It’s a constant, wordless negotiation of power and support.

Practical Steps to Improve Your Group's Health

You can't just "fix" a dynamic overnight. It's a garden, not a machine. You have to tend to it.

Establish a Shared Purpose

If people don't know why they're in the room, they will start creating their own reasons. Usually, those reasons involve protecting their own ego or territory. Be annoyingly clear about the "Why."

Encourage the "Quiet Ones"

In almost every group, 20% of the people do 80% of the talking. This is a dynamic failure. Use techniques like "brainwriting"—where everyone writes down ideas privately before sharing—to break the dominance of the loudest voices.

Call Out the "Elephant"

If there’s tension, talk about it. "Hey, I feel like we're all being a bit careful with our words today. Why is that?" It’s awkward for ten seconds, but it saves ten weeks of passive-aggression.

Rotate Roles

Don't let the same person always take notes or always lead the brainstorming. Shifting roles forces people to see the group from a different perspective. It breaks the "calcification" of roles that happens over time.

Monitor the "Energy Drainers"

Sometimes, a bad dynamic is the result of one "toxic" individual. Research by Will Felps showed that a single "bad apple"—someone who is cynical, lazy, or interpersonal aggressive—can reduce a group's performance by 30% to 40%. You have to address the behavior, or the dynamic will warp to accommodate the toxicity.

📖 Related: Maui Land & Pineapple Company Inc: What’s Actually Left After the Fruit Is Gone

The Bottom Line on Group Dynamics

Understanding the meaning of group dynamics isn't about memorizing textbooks. It's about being an observer of human nature. It's about realizing that when a team fails, it’s rarely because they weren't smart enough. It’s usually because they couldn't figure out how to be a "we" instead of a bunch of "me's."

Stop looking at the tasks. Start looking at the ties between the people doing the tasks. That is where the real work happens.

Immediate Action Items:

- Audit your next meeting: Watch who speaks, who gets interrupted, and who looks at their phone when a specific person talks.

- Define the 'Unspoken Rules': Ask your team to name one "rule" everyone follows that isn't in any handbook.

- Check for Safety: Ask yourself: "When was the last time someone in this group admitted to a mistake?" If you can't remember, your dynamic is in trouble.