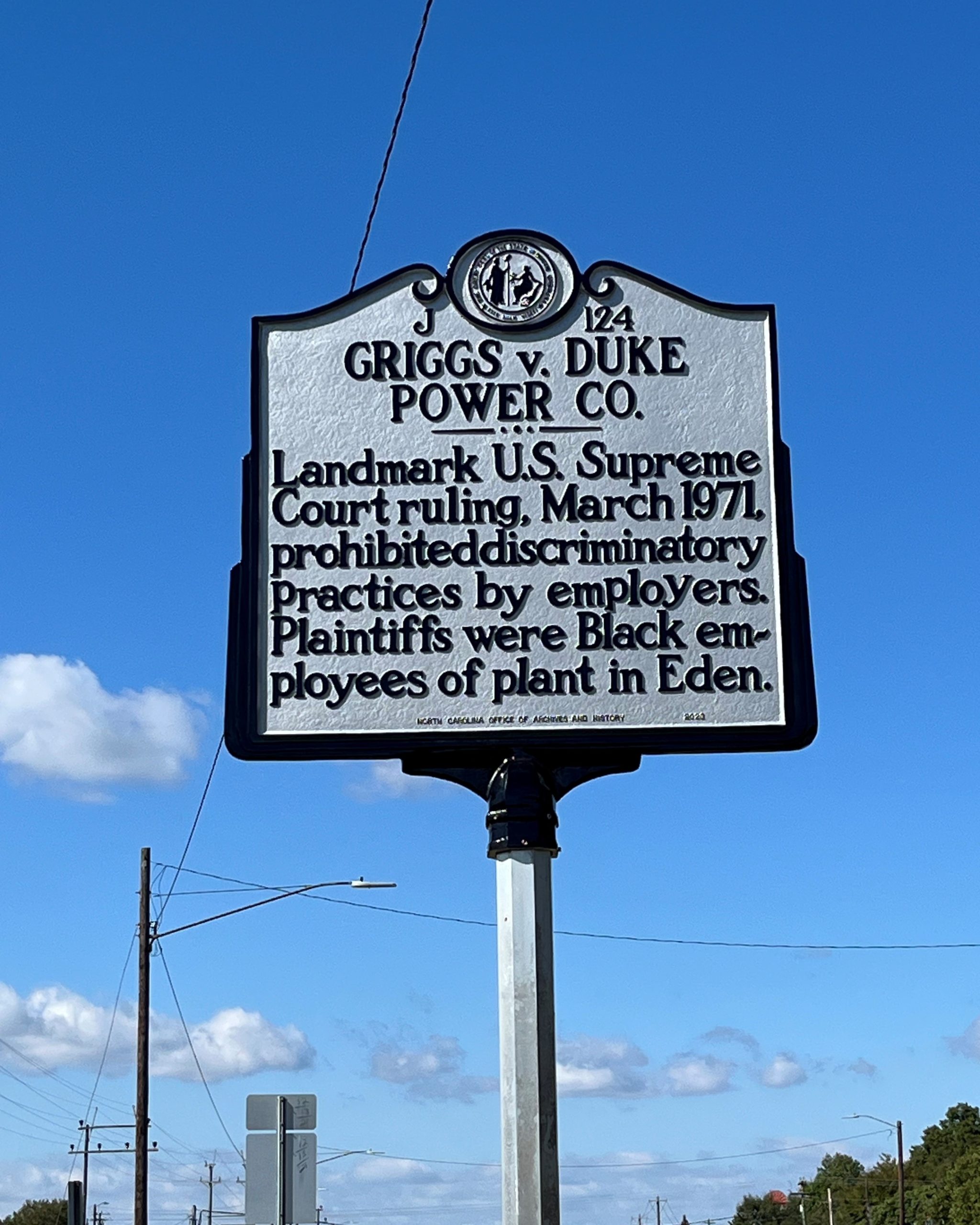

You’ve probably applied for a job and wondered why on earth they’re asking you to take a math test or why they need a high school diploma for a warehouse gig. Honestly, if it weren't for a group of thirteen Black laborers in North Carolina back in the late 60s, your job hunt would look a lot different—and probably a lot more unfair. We’re talking about Griggs v Duke Power Co, a 1971 Supreme Court powerhouse that basically invented the rulebook for modern workplace equality.

Before this case, companies could pretty much block whoever they wanted. They didn’t have to say "we don't hire Black people" anymore—the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had already made that illegal. Instead, they just used "neutral" hurdles. They’d say, "Sure, you can have the job, but only if you have a high school diploma and pass two IQ tests." It sounded fair on paper, right? Same rules for everyone. But in 1960s North Carolina, those rules were a trap.

What actually happened at the Dan River Steam Station?

The Dan River Steam Station was a power plant in Draper, North Carolina, owned by the Duke Power Company. For years, the company had a blatant policy of segregation. Black employees were only allowed to work in the Labor department, which was the lowest-paying sector. Everything else—Operations, Maintenance, Laboratory—was strictly for white workers.

Then came July 2, 1965. That was the day the Civil Rights Act officially kicked in.

Duke Power couldn't keep its "white only" signs up anymore. So, they got creative. They instituted a new policy: to get into any department except Labor, you needed a high school diploma. If you were already working there and wanted to transfer out of Labor, you had to pass two aptitude tests: the Wonderlic Personnel Test and the Bennett Mechanical Comprehension Test.

Here is the kicker: Willie Griggs and his colleagues realized that these tests had nothing to do with shoveling coal or fixing pipes. White employees who had been hired before the diploma requirement were doing just fine in those high-paying jobs without a degree. Meanwhile, because of the crappy, segregated school systems in North Carolina at the time, Black applicants were far less likely to have that diploma or pass tests designed for a different demographic.

✨ Don't miss: Getting a Mortgage on a 300k Home Without Overpaying

The math was brutal

In 1960, only 12% of Black males in North Carolina had a high school education compared to 34% of white males. When it came to the tests, 58% of whites passed, but only 6% of Black applicants did. It wasn't that the Black workers weren't capable; it was that the game was rigged.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund took up the case. They argued that even if Duke Power didn't intend to discriminate, the result was the same. It was a barrier that served no business purpose.

Why the Supreme Court's decision was a total bombshell

When the case finally hit the Supreme Court, Chief Justice Warren Burger—who, interestingly, was appointed by Richard Nixon—wrote the unanimous 8-0 opinion. It was a rare moment of total agreement.

The Court basically told Duke Power: "Intent doesn't matter if the outcome is broken."

This birthed the "disparate impact" theory. It shifted the focus from the employer's heart to the employer's results. Burger used a famous analogy: the law doesn't just prohibit the "open door" from being locked; it prohibits the "built-in" headwinds that make it impossible for certain groups to walk through.

🔗 Read more: Class A Berkshire Hathaway Stock Price: Why $740,000 Is Only Half the Story

The "Business Necessity" Rule

This is the part that still affects your career today. The Court ruled that if a hiring practice (like a test or a degree requirement) disproportionately excludes a protected group, the employer must prove that the requirement is "job-related and consistent with business necessity."

Basically:

- If you require a PhD to flip burgers, and that PhD requirement keeps certain races out, you're going to lose in court.

- If you require a heavy-lifting test for a construction job, and it happens to exclude more women than men, you might be okay if you can prove that the job actually requires lifting 100 pounds all day.

Griggs v Duke Power Co made it so the "diploma" wasn't a magic shield for companies to hide behind. If the test doesn't measure the ability to do the job, the test is illegal.

Myths about Griggs that just won't die

Some people think this case meant companies can't use tests at all. That’s just wrong. Companies use tests all the time—just look at coding interviews or physicals for firefighters. The difference is "validation." After Griggs v Duke Power Co, HR departments had to start hiring industrial-organizational psychologists to actually prove their tests worked.

Another misconception is that this was about "quotas." It wasn't. Justice Burger specifically said the law doesn't require "that any person be hired simply because he was formerly the subject of discrimination." It just requires that the "track" be level. If two people are running the same race, you can't put hurdles in front of only one of them and call it a fair contest.

💡 You might also like: Getting a music business degree online: What most people get wrong about the industry

How this case still shapes your 2026 job hunt

Even now, fifty-five years later, we see the echoes of Griggs. Think about the current debate over "degree inflation." Many tech companies are dropping the "Bachelor’s Degree Required" line from their job postings. Why? Because they realized those degrees weren't actually predicting who would be a good programmer.

In a way, they are doing exactly what the Supreme Court suggested in 1971: looking at actual skills rather than credentials that might unfairly lock people out of the middle class.

But there’s a new frontier: Algorithms. AI-driven hiring tools are the new "aptitude tests." If an AI screens out resumes based on zip codes or names, and those zip codes correlate with race, that is a direct violation of the principles laid out in Griggs. The law hasn't changed; the technology has. Lawyers are currently using the Griggs precedent to sue companies whose "black box" algorithms show disparate impact.

Real-world ripple effects

- The Firefighter Exams: In the 2000s, New York City had to throw out its entrance exam for firefighters because it didn't actually predict who would be a good firefighter and it disproportionately failed Black and Hispanic applicants.

- Credit Checks: Some states have banned using credit scores for employment because of the disparate impact on people from marginalized communities who have historically had less access to traditional banking.

- Criminal Background Checks: The EEOC (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission) uses the Griggs logic to tell employers they can't have a "blanket ban" on anyone with a record, as that can be a form of indirect discrimination.

What you should do with this information

If you're a business owner or a hiring manager, you can't just wing it. You need to look at your "requirements" and ask: "Is this a real need or a habit?"

If you are a job seeker who feels like a "neutral" requirement is unfairly blocking you, knowing the history of Griggs v Duke Power Co gives you the language to understand your rights. You aren't just complaining; you're pointing out a legal standard that has been the law of the land for decades.

Practical Steps for Employers

- Audit your job descriptions. If you have "Master's Degree Required" for a role that has been successfully filled by people with Associate degrees in the past, change it. You're opening yourself up to legal risk.

- Validate your tests. If you use a personality or cognitive test, ask the vendor for a "validation study." If they can't show that it's job-related and non-discriminatory, stop using it.

- Focus on "Essential Functions." When writing a job post, stick to what the person actually does every day.

Practical Steps for Employees

- Request feedback. If you’re rejected based on a specific test, it doesn’t hurt to ask how that test relates to the daily tasks of the role.

- Document everything. If you see a pattern where only people of a certain background are passing "neutral" hurdles in your company, keep a record. Disparate impact is proven through statistics and data.

- Look for "Skills-First" companies. Many modern employers are moving toward performance-based hiring (like giving you a small project to do) rather than relying on old-school credentials. These companies are usually more in line with the spirit of the Griggs ruling.

The Dan River Steam Station workers weren't looking to overthrow the system. They just wanted to move out of the Labor department and earn a better living for their families. They won. And because they won, the burden shifted from the worker to the employer to prove that the "hurdles" are actually necessary. It's a subtle change, but it's the reason why "because I said so" is no longer a valid legal defense for a job requirement.