It’s one of those moments that feels frozen in time. If you’re old enough to remember the 1988 Seoul Olympics, you probably remember the sound first. A "clank." A hollow, metallic thud that didn't belong at a pool.

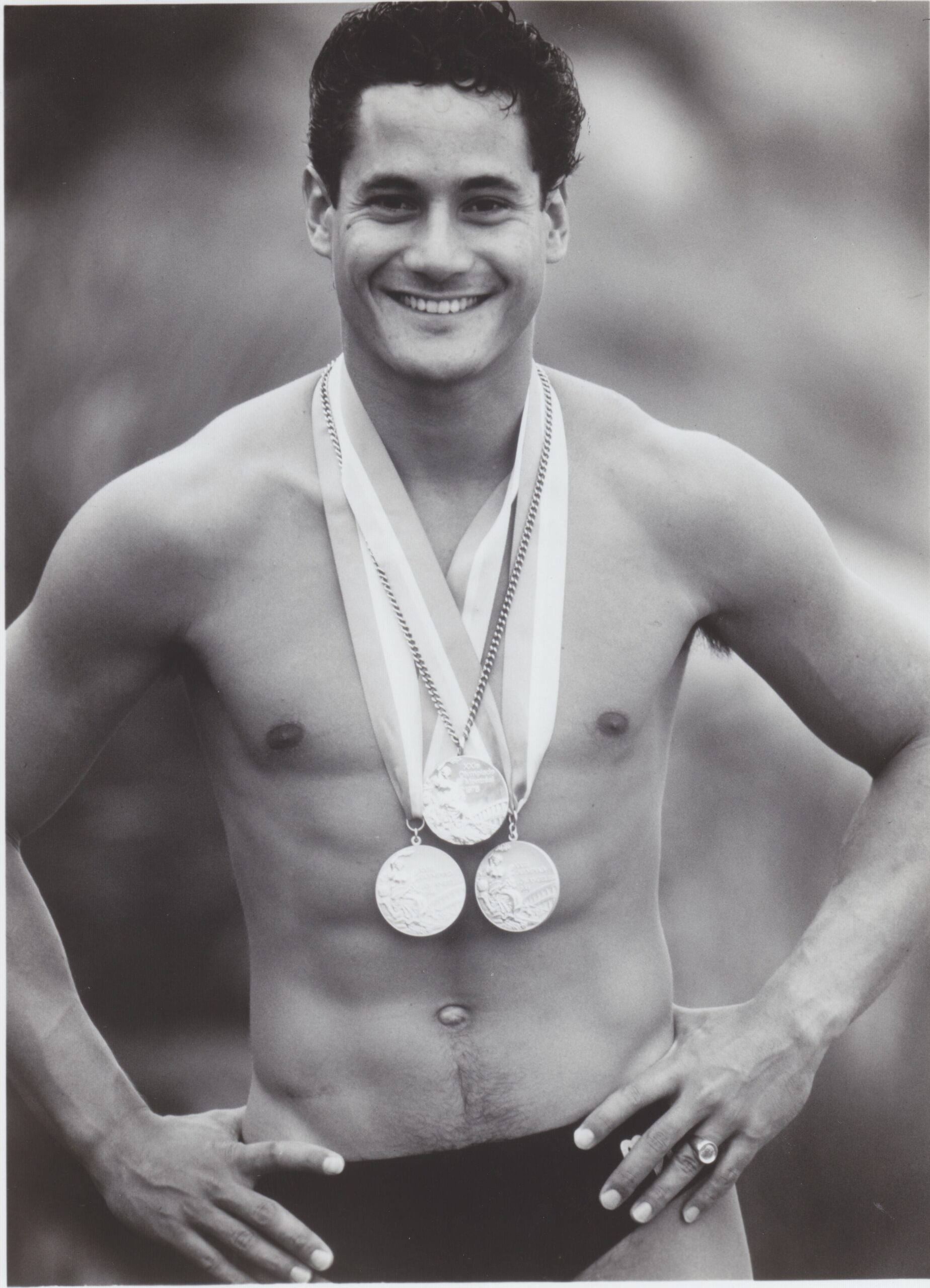

Greg Louganis was the greatest diver on the planet. He was the defending double-gold medalist from 1984. He was perfection in a Speedo. But during the preliminary rounds of the 3-meter springboard, something went horribly wrong.

The Sound That Chilled the Arena

He was performing his ninth dive—a reverse 2.5-somersault pike. It’s a dive he’d done thousands of times. But this time, he was too close. As he came out of the tuck, the back of his head slammed against the end of the yellow springboard.

He plummeted into the water with a sickening splash. For a few seconds, the crowd was dead silent. People held their breath, waiting for him to surface. When he finally did, he was clutching his head.

A red cloud started blooming in the water.

The Secret Fear Nobody Knew About

Most of the world saw a champion with a concussion and a bloody scalp. They saw "the comeback kid." But inside Louganis's head, there was a terror far worse than a head injury.

💡 You might also like: Tonya Johnson: The Real Story Behind Saquon Barkley's Mom and His NFL Journey

Six months before the Games, Greg Louganis had tested positive for HIV.

Back then, in 1988, HIV was basically a death sentence. The stigma was crushing. He hadn't told the Olympic Committee. He hadn't told his teammates. Only a tiny circle—his coach Ron O'Brien and a few others—knew.

As he walked out of the pool with blood trickling down his neck, he was "paralyzed with fear." That’s how he described it later in his book, Breaking the Surface. He wasn't just worried about the gold medal; he was terrified he had just put every other diver in the pool at risk. He was terrified for the doctor, James Puffer, who was about to stitch him up.

The Stitches and the Return

Dr. Puffer didn't wear gloves.

In the late 80s, the "universal precautions" we take for granted now weren't standard yet. The doctor quickly put four temporary stitches in Louganis’s head right there at the venue. Greg sat there, vibrating with anxiety, wondering if he should say something. "Do I tell him? If I tell him, will they kick me out? Will the world know?"

📖 Related: Tom Brady Throwing Motion: What Most People Get Wrong

He stayed silent.

Amazingly, just 35 minutes after hitting the board, Louganis climbed back up those steps. His next dive? The exact same type of dive that had just cracked his skull open. He nailed it.

He didn't just qualify; he went on to win the gold medal the next day. A week later, he won another gold on the 10-meter platform, becoming the first man to win both events in consecutive Olympics.

The Backlash and the Science

When Greg finally came out as HIV-positive in 1995, the reaction wasn't all supportive. A lot of people were angry. They felt he had been reckless by bleeding into a public pool and letting a doctor treat him without warning.

But here’s the reality: the risk was essentially zero.

👉 See also: The Philadelphia Phillies Boston Red Sox Rivalry: Why This Interleague Matchup Always Feels Personal

The CDC and experts like Dr. Anthony Fauci eventually spoke up to clear the air. Why? Because chlorine kills HIV. Even if the chlorine hadn't done the job, the sheer volume of water in an Olympic-sized pool would have diluted the virus to a point where transmission was virtually impossible.

As for Dr. Puffer, he tested negative. The skin is a remarkably good barrier, and without an open wound on the doctor's hands, the virus had nowhere to go.

Why the Accident Matters Now

Looking back, the moment Greg Louganis hits head isn't just a sports highlight. It’s a snapshot of a very specific, scary time in medical history. It changed how we handle blood in sports. After this incident, the "blood rule" became a thing—if an athlete is bleeding, they leave the field immediately, and officials wear gloves.

It also humanized a diagnosis that, at the time, was treated with nothing but horror.

What We Can Learn From the Seoul Accident

If you're an athlete or just someone interested in the history of the Games, there are a few real takeaways from this saga:

- Resilience is a Choice: Louganis didn't win because he wasn't hurt; he won because he decided the injury didn't define the rest of his day.

- Stigma Kills Honesty: The reason Greg stayed silent wasn't malice. It was the fear of being ostracized. When we create environments where people can be honest about their health, everyone is safer.

- Science Over Panic: The 1995 backlash was fueled by fear, not facts. Always look for the data—like the fact that chlorinated water is a highly hostile environment for viruses.

Today, Greg Louganis is in his 60s, healthy, and still an advocate for both the LGBTQ+ community and HIV awareness. The scar on the back of his head is still there, a tiny reminder of the day he hit the board and the much bigger battle he was fighting under the surface.

To dive deeper into the history of the 1988 Games, you can research the official Olympic archives or look for the documentary Back on Board: Greg Louganis, which gives a much more intimate look at his life during those years.