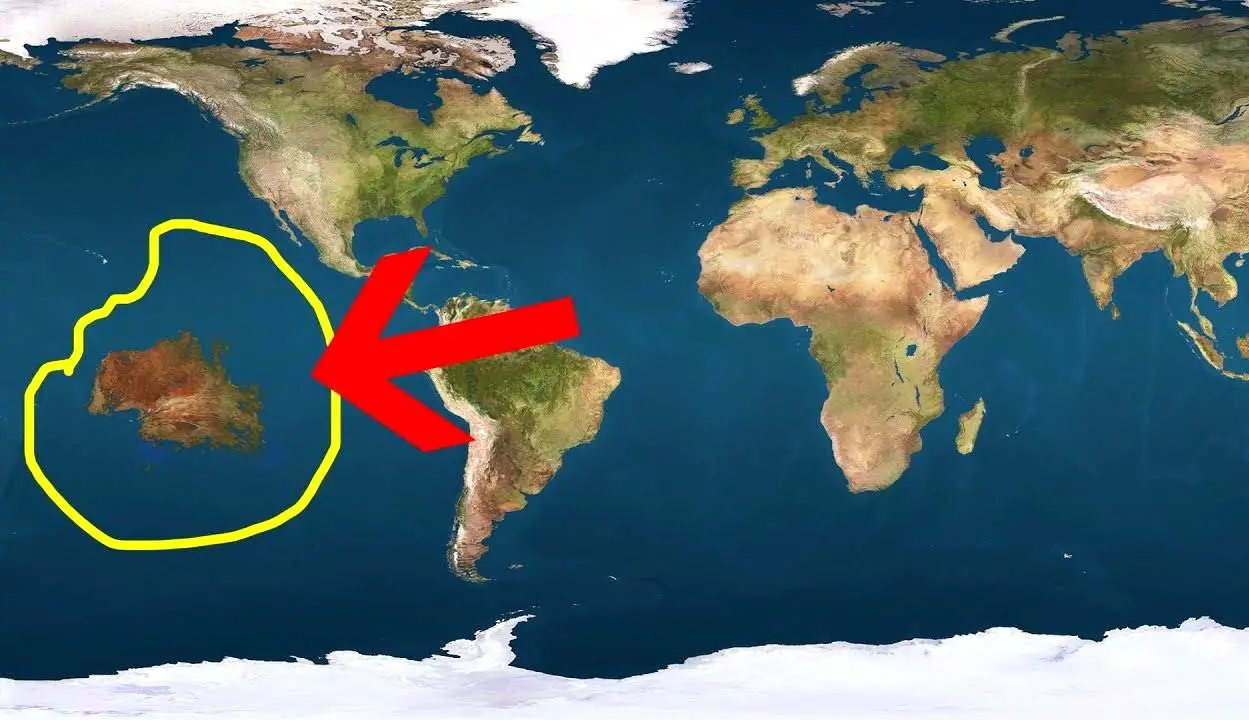

You’ve probably seen the viral memes. There is this terrifying idea floating around that if you pull up Google Earth and zoom into the North Pacific, you’ll see a literal island of trash—a solid, crusty landmass of plastic bottles and old fishing nets that you could practically walk on. Honestly, it makes for a great horror story. But if you actually try to find a great pacific garbage patch satellite image, you’re going to be disappointed. You’ll see nothing but vast, deep blue water.

This isn't a conspiracy. It’s science.

The reality of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) is arguably much scarier than a giant floating island because it is invisible to the naked eye from space. We’re talking about a "soup," not a "dump." It’s a massive concentration of microplastics, most of which are smaller than a grain of rice. When people go looking for that definitive satellite shot, they are looking for something that doesn't exist in the way we've been taught to imagine it.

The Optical Illusion of the "Trash Island"

Why can't we just snap a photo of it? Most of the plastic out there has been pulverized by the sun and the waves. Photodegradation breaks a sturdy laundry detergent bottle into millions of tiny shards. These shards don't sit on the surface like a carpet; they hover in the upper water column.

Satellites use optical sensors. They see what we see. If the plastic is translucent or bobbing just six inches below the surface, the light reflecting off the ocean drowns it out. Capturing a great pacific garbage patch satellite image that actually shows the "patch" requires specialized technology that goes way beyond standard photography.

It's about the sensors, not the camera

To actually "see" the patch from orbit, researchers like those at the University of Michigan have started using something called CYGNSS (Cyclone Global Navigation Satellite System). It’s not taking a picture in the traditional sense. Instead, it measures ocean roughness. Water that is full of microplastics behaves differently; it’s smoother because the plastic dampens the waves. When you look at a map generated by this data, you finally see the "blob" people are looking for. It's a heatmap of debris density, not a photo of a floating tire.

What Real Data Tells Us (And What It Doesn't)

The GPGP sits between Hawaii and California. It’s huge. We're talking about an area twice the size of Texas, or three times the size of France, depending on which study you're reading. According to The Ocean Cleanup—an organization founded by Boyan Slat that is actually out there dragging nets through the water—the patch contains roughly 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic.

📖 Related: Why the Icon On Off Switch Still Confuses Everyone

Think about that number. 1.8 trillion.

Most of that weight, surprisingly, comes from "ghost gear." These are abandoned fishing nets that can be dozens of meters long. While a great pacific garbage patch satellite image might miss a single net, these nets are the primary killers of marine life in the vortex. They entangle whales, turtles, and sharks in a process that continues for decades because the plastic simply won't go away.

The role of the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre

The patch exists because of a gyre. This is basically a massive, slow-moving whirlpool created by four ocean currents: the North Pacific, the California, the North Equatorial, and the Kuroshio. These currents pull debris into the center and trap it. It’s a dead zone for movement but a magnet for everything we throw away.

Charles Moore, the oceanographer who "discovered" the patch in 1997, famously described it as a plastic soup. He was sailing back from a race and found himself surrounded by debris day after day. He didn't find an island. He found an endless, thin layer of trash. If he couldn't see a solid mass from the deck of a boat, a satellite definitely won't see it from 400 miles up.

Technology is Catching Up to the Trash

We are getting better at tracking it, though. Scientists are now using Sentinel-2 satellites, which belong to the European Space Agency. These satellites use multispectral imaging. By looking at specific wavelengths of light that plastic reflects differently than water, they can spot "aggregations" of debris.

It’s a bit like using a blacklight to find a stain on a carpet. To the naked eye, the carpet looks fine. Under the right light, the mess is obvious.

- Spaceborne Radar: Used to detect the "smoothing" effect of plastic on waves.

- AI Analysis: Algorithms now scan thousands of satellite images to find "spectral signatures" of floating objects.

- Drifter Buoys: These aren't satellites, but they provide the "ground truth" that helps calibrate satellite data.

NASA has also played a role. By using their ECCO (Estimating the Circulation and Climate of the Ocean) model, they can predict where the trash will go next. This is vital because the patch isn't static. It breathes. It expands and contracts based on seasonal shifts and El Niño events.

✨ Don't miss: Why a Wheelchair That Climbs Stairs Is Finally Becoming Reality

Why the "Invisible" Nature is a Problem

The fact that we don't have a shocking, clear great pacific garbage patch satellite image is actually a major hurdle for environmental policy. Humans are visual creatures. If we see a giant pile of burning tires, we want to put it out. If we see a clear blue ocean that happens to have the chemical equivalent of a poison pill dissolved in it, we tend to ignore it.

Microplastics are the real villain here. They absorb Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) like PCBs and DDT. Then, a small fish eats the plastic. A bigger fish eats the small fish. Eventually, that plastic—and the toxins it carried—ends up on a dinner plate.

It’s a biological magnification nightmare.

The Misconception of "Cleaning It Up"

People often ask, "Why don't we just go out there with a big vacuum?"

Because you'd be vacuuming the ocean.

The density of the plastic is actually quite low in terms of grams per cubic meter. You would have to filter massive amounts of water just to get a handful of plastic, and in the process, you would kill a staggering amount of neuston—the tiny organisms that live on the surface of the water and form the base of the food chain.

The Ocean Cleanup is trying a different approach by using long, floating barriers that act like an artificial coastline. They use the ocean's own currents to concentrate the plastic into a "retention zone" which is then emptied by a ship. It's working, but it's a drop in the bucket. They've collected thousands of tons, but millions of tons are still out there.

Actionable Insights: What Can Actually Be Done?

If we can't see the problem easily from space, we have to tackle it at the source. The GPGP is a symptom; the river systems are the disease. Research suggests that about 80% of ocean plastic comes from just 1,000 rivers globally.

👉 See also: The 2026 Data Breach Today: Why Your Passkeys Might Be at Risk

How to contribute to the solution

Stopping the flow is more effective than cleaning the center of the ocean. Supporting initiatives that install "trash fences" or "interceptors" in high-pollution river mouths in places like Indonesia, the Philippines, and Central America has a much higher ROI than any deep-sea mission.

- Avoid Microbeads: Check your skincare labels. Polyethylene is a common culprit.

- Support Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) Laws: These laws hold companies accountable for the entire lifecycle of their packaging.

- Ghost Gear Initiatives: Support organizations like Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI) that work specifically with fishing fleets to track and recover lost nets.

The hunt for the perfect great pacific garbage patch satellite image usually ends in a lesson about physics and optics. We want a simple picture of a simple problem. Instead, we have a complex, invisible disaster that requires high-tech sensors and global policy shifts to solve.

The lack of a visible "island" doesn't mean the ocean is clean; it means the pollution has become part of the water itself. Identifying the patch through data visualization and spectral analysis is our best shot at monitoring the health of the North Pacific. The more we rely on actual data rather than viral myths, the closer we get to actual solutions.

Focus on the rivers. Support the interceptors. Stop looking for an island and start looking at the chemistry of the water. That is where the real battle for the Pacific is being fought.