If you search for a great pacific garbage patch picture, you're probably expecting to see a literal island of trash. You might be picturing a solid landmass made of plastic bottles, old tires, and discarded fishing nets, perhaps something so dense you could actually walk across it with a pair of sturdy boots.

It’s a common mental image. It’s also wrong.

The reality of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) is actually much more unsettling than a giant floating junkyard. Honestly, if it were a solid island, we might have an easier time cleaning it up. Instead, scientists like those at The Ocean Cleanup or researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) describe it more like a "plastic soup." It’s a massive, swirling vortex of microplastics that are often invisible to the naked eye from a satellite or even from the deck of a boat.

That’s why finding a definitive, wide-angle great pacific garbage patch picture that captures the whole scale of the mess is basically impossible. You’re looking for a photo of a ghost.

The Viral Photos That Are Actually Fake News

Let’s talk about those photos that go viral on social media every few months. You've seen them. There's one of a massive wave choked with trash, or a dense carpet of plastic in a narrow harbor. Usually, these aren't the Great Pacific Garbage Patch at all. Most of those images are taken in polluted harbors in Manila or river mouths in Central America after a heavy rain.

✨ Don't miss: Hicks Funeral Home Obituaries Elkton MD: What Most People Get Wrong

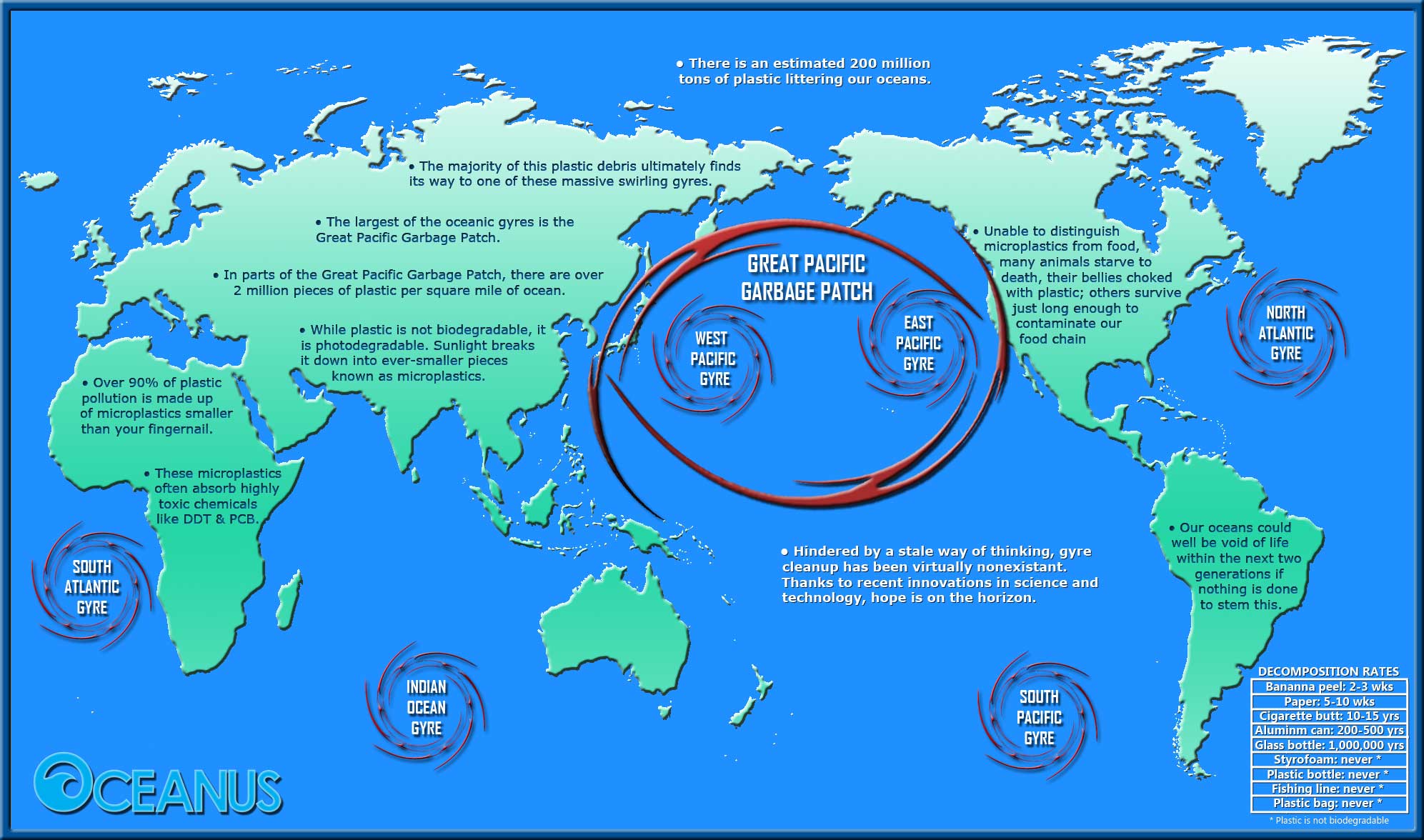

The GPGP is located in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, a remote area between Hawaii and California. It's thousands of miles from the nearest coastline.

Because the patch is created by rotating ocean currents, it draws debris in and traps it. But the sun is a brutal force out there. Photodegradation—a fancy word for the sun breaking things down—turns large plastic jugs and crates into tiny, confetti-sized bits. These microplastics (defined as pieces smaller than 5 millimeters) don't show up well in a standard great pacific garbage patch picture. They float just beneath the surface, suspended in the water column like fish food.

Why the Camera Can't Capture the Scale

Captain Charles Moore, who is widely credited with "discovering" the patch in 1997 while sailing home from a yacht race, didn't look out and see a mountain of trash. He looked out and noticed a constant "plastic haze" in what should have been pristine blue water.

Imagine a bottle of Italian dressing.

The herbs are the plastic.

The oil is the ocean.

Even if you take a photo of the bottle, you might only see a few flakes here and there, but you know the whole mixture is saturated.

The GPGP covers an estimated surface area of 1.6 million square kilometers. To put that in perspective, that’s about three times the size of France. If you flew over it in a plane, you wouldn't see a giant brown mass. You’d see a lot of blue water. Occasionally, you might spot a "ghost net"—a tangled mess of abandoned fishing gear—or a stray crate. But the true bulk of the weight is in trillions of tiny pieces that a camera sensor just can't pick up from a distance.

What a Real Great Pacific Garbage Patch Picture Shows

If you want to see what the patch actually looks like, you have to look at photos taken by organizations like The Ocean Cleanup during their extraction missions. These aren't panoramic shots of the horizon; they are close-ups of "tows."

When they pull their massive retention systems through the water, they bring up a horrifying slurry. This is where you see the real great pacific garbage patch picture:

- Baskets full of "nurdles" (pre-production plastic pellets).

- Toothbrushes with the bristles still intact but the handles bleached white.

- Sea turtles entangled in nylon ropes.

- Crates from the 1970s that look like they were tossed overboard yesterday.

One of the most famous and heartbreaking images associated with the patch isn't even of the water. It’s the work of photographer Chris Jordan on Midway Atoll. He took photos of albatross carcasses where the flesh had decayed, leaving behind a pile of colorful plastic rings, lighters, and bottle caps where the bird's stomach used to be. That is the biological reality of the garbage patch. It’s not a floating island; it’s a death trap for marine life that mistakes the debris for food.

The Science of the "Soup"

According to a study published in Scientific Reports by Laurent Lebreton and his team, there are over 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic in the patch.

Weight-wise, fishing nets actually make up about 46% of the mass. These "ghost nets" are the most dangerous part of the great pacific garbage patch picture that we don't talk about enough. They float around, continuing to "fish" for centuries, drowning seals and crushing coral reefs when they eventually drift into shallower waters.

The remaining mass is mostly hard plastics—polyethylene and polypropylene. Think of the things you use once and throw away. To-go containers. Lids. Straws.

It's a common misconception that this plastic all comes from people tossing trash off cruise ships. While some of it does, a huge portion is land-based waste that makes its way through rivers and into the sea. Once it hits the gyre, it’s stuck. It’s a graveyard with no exit strategy.

Why We Can't Just "Scoop It Up"

People often ask why we don't just send a fleet of boats with nets to clean it all up.

It's not that simple.

First, the area is too big. If you tried to use conventional nets, you'd kill a massive amount of marine life—plankton, jellyfish, and small fish—along with the plastic. It would be like trying to clean a forest of trash by using a bulldozer that knocks down every tree in the process.

Secondly, it's expensive. Most of the patch is in international waters. No single country wants to foot the bill for a mess that everyone contributed to.

Boyan Slat and his team at The Ocean Cleanup have been working on passive systems that use the ocean’s own currents to concentrate the plastic. They’ve had some success with their "System 03," which is a massive floating barrier. When you see a great pacific garbage patch picture from their missions, you see hope, but you also see the sheer, exhausting volume of the work left to do. Every time they empty a bag, there's a billion more pieces waiting in the current.

Acknowledging the Limitations of Imagery

We live in a visual culture. If we can't see a "garbage island" on Google Earth, we tend to think the problem is exaggerated.

But the "invisibility" of the GPGP is exactly why it’s so dangerous. Microplastics act like sponges for toxic chemicals like PCBs and DDT. Small fish eat the plastic, the toxins build up in their fat, and eventually, those toxins move up the food chain to the fish you buy at the grocery store.

You aren't just looking at a great pacific garbage patch picture; you might be looking at the future of your dinner plate.

The "island" narrative was a well-intentioned metaphor used by activists in the early 2000s to get people to care. It worked. It got headlines. But now, it’s almost backfired because skeptics point to the lack of "land" as evidence that the patch doesn't exist. It exists. It’s just more of a smog than a landfill.

How to Look at the Problem Differently

If you really want to understand the impact of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, stop looking for a photo of a floating trash mountain and start looking at your own trash bin.

The plastic in the North Pacific is a snapshot of global consumption habits over the last 60 years.

There are pieces in that patch that are older than you are. Because plastic doesn't "go away," it just gets smaller. Every piece of plastic ever made still exists in some form, unless it’s been incinerated.

Actionable Steps for the Real World

Cleaning the ocean is the "end-of-pipe" solution. It’s necessary, but it’s like trying to mop up a bathroom while the tub is still overflowing. You have to turn off the tap.

- Support Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) Laws: These are laws that hold companies accountable for the entire lifecycle of their packaging. If a company makes a plastic bottle, they should be responsible for making sure it gets recycled, not the taxpayer or the ocean.

- Audit Your Own Plastic Footprint: You don't have to be perfect. Just look at the "big four": bags, bottles, straws, and coffee cups. Swapping these out makes a dent over a lifetime.

- Look for "Microplastic-Free" Labels: Many personal care products, like face scrubs, used to contain plastic microbeads. While many countries have banned these, they still exist in some formulations globally.

- Contribute to Research, Not Just Cleanup: Support organizations like the 5 Gyres Institute or the Algalita Marine Research Foundation. They do the hard work of sampling the water to understand how the plastic is changing.

- Question the Visuals: Next time you see a great pacific garbage patch picture on social media, check the source. Is it actually the Pacific, or is it a beach in Bali? Understanding the true nature of the "soup" is the first step in actually fixing it.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is a symptom of a systemic design flaw. We created a material designed to last forever and used it for products designed to be used for five minutes. No single photo can capture that level of irony, but the data—and the dead wildlife—tells the story clearly enough.

Focus on reducing the flow of new plastic into the system. Support technologies that target river-borne plastic before it ever reaches the open ocean. Intercepting trash in the 1,000 most polluting rivers could prevent 80% of ocean plastic pollution. That is a measurable, achievable goal that doesn't rely on scouring millions of miles of open sea for "invisible" particles.