You’ve probably seen the viral ones. There’s a photo of a diver swimming through a literal wall of plastic bags, or maybe that shot of a sea turtle tangled in a neon green fishing net. We see great pacific garbage patch photos and our brains immediately jump to a specific image: a solid, floating island of trash you could practically walk across.

It makes sense. We like visual metaphors. But honestly? That "island" doesn't exist. Not in the way you think.

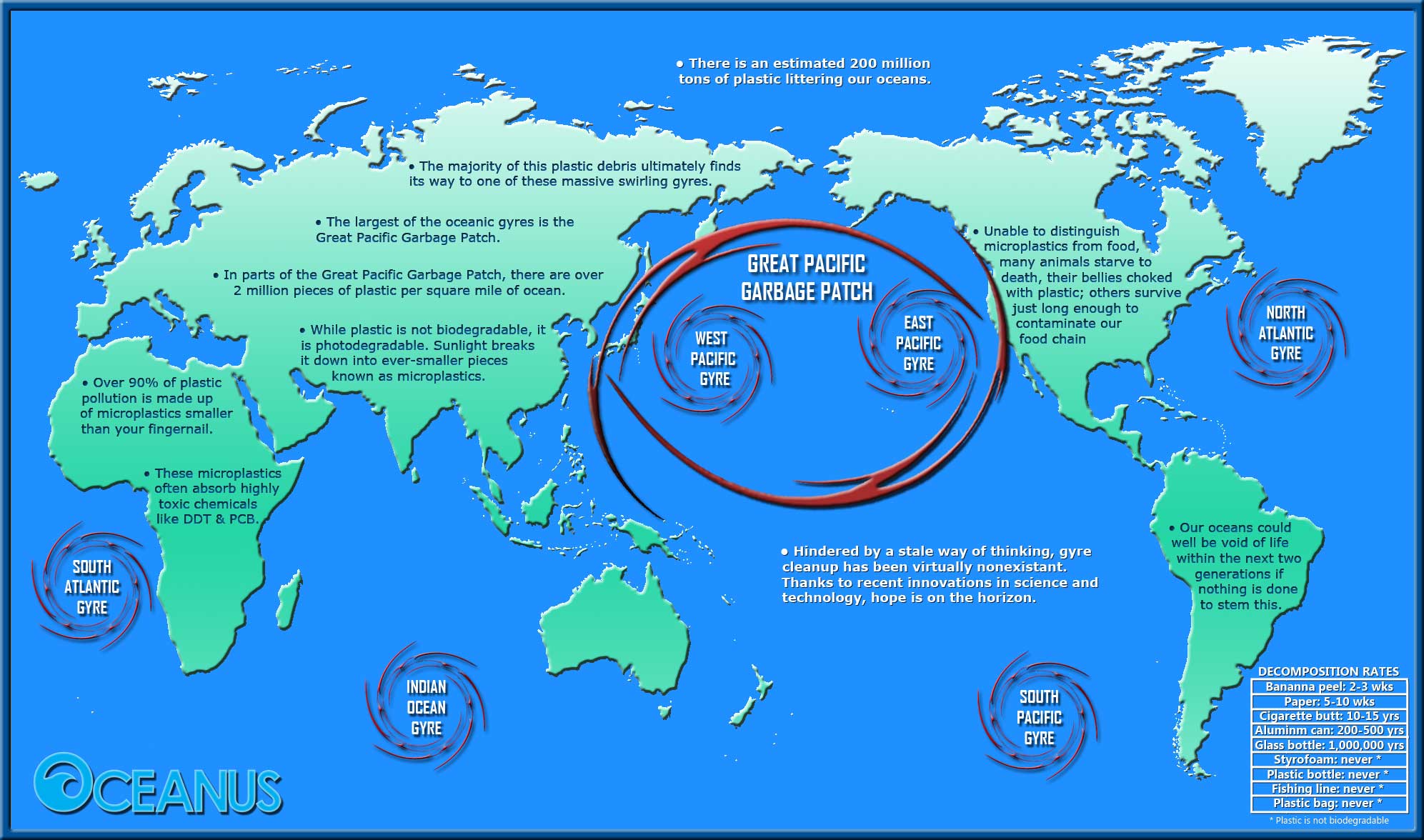

If you flew a plane over the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre right now, you wouldn't see a giant landmass of junk. You'd see blue water. This is the big paradox of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP). It is simultaneously a massive ecological disaster and almost entirely invisible to the naked eye from a distance. Capturing it on camera is actually a nightmare for photojournalists because the "patch" is more like a thin soup than a landfill.

The Trouble With Seeing the Invisible

Most people get frustrated when they realize those dramatic "island of trash" photos are often taken in polluted harbors in Manila or the Caribbean, not the middle of the Pacific. It feels like a bait-and-switch. But the reality shown in authentic great pacific garbage patch photos is actually much scarier than a floating island.

The GPGP is located between Hawaii and California. It’s huge. We're talking about 1.6 million square kilometers, which is roughly twice the size of Texas. But because the sun and the waves break plastic down into tiny bits through photodegradation, most of the debris is microplastic. These pieces are smaller than a grain of rice.

How do you photograph a trillion grains of rice scattered across half an ocean? You don't. At least, not easily.

When researchers like those from The Ocean Cleanup or the Algalita Marine Research Foundation document the area, they use fine-mesh nets called manta trawls. They pull these through the water, and when they lift them up, that’s where the horror shows up. The photos show a thick, colorful sludge of pellets, shards, and fibers. It’s a plastic confetti graveyard.

Why the "Garbage Island" Myth Persists

Charles Moore, the sailor who "discovered" the patch in 1997, didn't find a mountain of trash. He found himself sailing through a sea that just felt... off. He described it as a plastic soup.

Media outlets, however, needed a visual hook. "Soup" isn't a great headline. "Island" is. Over time, the internet started tagging any photo of a polluted river or a coastal disaster as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. This has led to a lot of skepticism. People go looking for the island on Google Earth, don't see it, and assume the whole thing is a hoax. It’s not. It’s just a different kind of mess.

What Real Great Pacific Garbage Patch Photos Actually Document

If you look at verified imagery from organizations like NOAA or the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, the visuals fall into three distinct categories.

- Ghost Gear: These are the big items. Discarded fishing nets—often called "ghost nets"—make up about 46% of the total mass of the GPGP. These are the most photogenic and heartbreaking parts of the patch. You’ll see photos of these massive, tangled webs of polypropylene rope weighing several tons, often with dead sharks or turtles trapped inside.

- Hard Plastics: Think crates, buckets, and buoys. Curiously, a lot of the larger recognizable items in the patch have dates on them from the 70s, 80s, and 90s. Plastic doesn't go away. It just waits.

- The Microplastic Slurry: These photos are usually taken on the decks of research vessels. They show glass jars filled with seawater and thousands of tiny blue, white, and red flecks. This is the stuff that gets into the food chain.

The Ocean Cleanup, founded by Boyan Slat, has released some of the most high-definition great pacific garbage patch photos in recent years. Their aerial surveys using LiDAR and multi-spectral cameras can "see" the concentrations of plastic that a human eye would miss. They’ve even captured images of "megaplastics"—anything over 50cm—bobbing just below the surface.

The Ghost in the Machine: Ghost Nets and Entanglement

Let's talk about the nets. Honestly, they’re the real villains here. While straws and bags get all the PR, it's the industrial fishing gear that does the heavy lifting in the GPGP.

📖 Related: Leo Schofield and Bone Valley: What Really Happened to Michelle

When you see a photo of a massive clump of nets, you’re looking at a "ghost." These nets continue to fish long after they’ve been lost or cut loose by vessels. They trap heat, they block sunlight for plankton, and they act as "rafts" for invasive species. Photos of these nets often show them encrusted with barnacles and small crabs that have traveled thousands of miles from their native habitats.

It’s a weird, mobile ecosystem. A plastic one.

The Scale is Hard to Grasp

It’s helpful to look at the numbers if the photos feel underwhelming. Research published in Scientific Reports estimates there are about 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic in the patch. If you tried to count every piece of plastic shown in a single wide-angle shot of the GPGP, you couldn't. Most of it is suspended in the water column, not just sitting on top.

If you dive down, the "photo" changes. It’s not just a surface film. It’s a volumetric problem.

Can We Actually Clean It Up?

This is where the debate gets heated. Some scientists, like those quoted in Nature, argue that we should focus on the coasts. Their logic? Once plastic hits the open ocean and breaks into microplastics, it's basically impossible to recover without killing the neuston—the tiny organisms like blue sea slugs and violet snails that live on the surface.

Others, like the team at The Ocean Cleanup, believe we have to do both. They’ve deployed massive floating barriers—essentially giant U-shaped "artificial coastlines"—to corral the plastic. Their great pacific garbage patch photos showing "System 002" (nicknamed Jenny) hauling in 9,000 kilograms of trash in a single sweep were a proof-of-concept moment.

🔗 Read more: Construction of Border Wall: What Actually Happened and Where It Stands Now

But even they admit it's a monumental task. To clean the whole thing, you’d need dozens of these systems running for decades. And that’s only if we stop more plastic from flowing in.

A Note on Misinformation

You’ve probably seen a photo of a "bridge" of trash with a person walking on it. That’s usually a photo of the Citarum River in Indonesia or a flood-hit area in South Asia.

It’s important to be skeptical. Authentic great pacific garbage patch photos are rarely that "perfect." Real photos of the GPGP are often grainy, taken from high-altitude drones or from the deck of a boat looking down into the deep blue. The horror is in the persistence of the debris, not necessarily its density in one spot.

If the photo looks like a solid landfill where you can't see the water at all, it's almost certainly not the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. It's a river or a coastal inlet. The GPGP is a deep-ocean phenomenon.

The Human Element

We often forget that there are people out there right now, weeks away from the nearest coastline, documenting this. It’s lonely work. Photos of the crews on ships like the Maersk Tender show the physical toll of pulling this stuff out of the water. It’s slimy, it smells like rotting organic matter, and it’s heavy.

One of the most striking images isn't of the trash itself, but of a laundry basket pulled from the gyre. It looked brand new, except for the bite marks from a shark. That’s the reality of the GPGP: our domestic life colliding with the wildest parts of the planet.

✨ Don't miss: What Really Happened With the Shocking Public Suicide in West Dallas - Texas

How to Help Without Going to the Middle of the Ocean

Looking at great pacific garbage patch photos usually leaves people feeling pretty helpless. It's a big ocean. You’re just one person.

But the solution isn't actually in the middle of the Pacific. It's on land.

- Support Interceptors: Research shows that 1,000 rivers are responsible for roughly 80% of ocean plastic. Projects that put "trash fences" or "interceptors" at river mouths are statistically more effective than trying to catch plastic once it’s already reached the gyre.

- Audit Your Own Plastic: It’s boring advice, but it works. Look at the "hard plastics" in your life. The crates and buckets mentioned earlier? Those are the items that survive the decades-long journey to the GPGP.

- Pressure the Industry: Since nearly half the mass of the patch is fishing gear, supporting sustainable seafood certifications that track "gear loss" is huge.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is a monument to the "away" in "throwing things away." We thought the ocean was big enough to swallow our mistakes. The photos prove we were wrong. It didn't swallow them; it just collected them.

The next time you see a photo of the patch, look for the water. If you can see the blue through the plastic, you’re looking at the real thing. And that’s the version we should be most worried about.

Actionable Insights for the Conscious Viewer

- Verify the Source: Before sharing a "garbage island" photo, check if it’s from a reputable oceanographic institution like NOAA or a known research group like The Ocean Cleanup. If the water looks shallow or there are buildings in the background, it’s not the GPGP.

- Focus on "Ghost Gear": Educate others that the patch isn't just straws; it's a massive industrial fishing problem. Support brands that use reclaimed ocean plastic for high-durability goods, which helps fund the expensive recovery of these nets.

- Reduce Macro-Plastics: Since large items eventually become trillions of microplastics, preventing one plastic crate from entering a waterway is more effective than trying to filter a billion microplastic beads later.

- Stay Updated on Policy: Follow the progress of the UN Global Plastics Treaty. This is the legislative "hammer" needed to stop the flow of plastic at the source, making clean-up efforts actually sustainable in the long run.