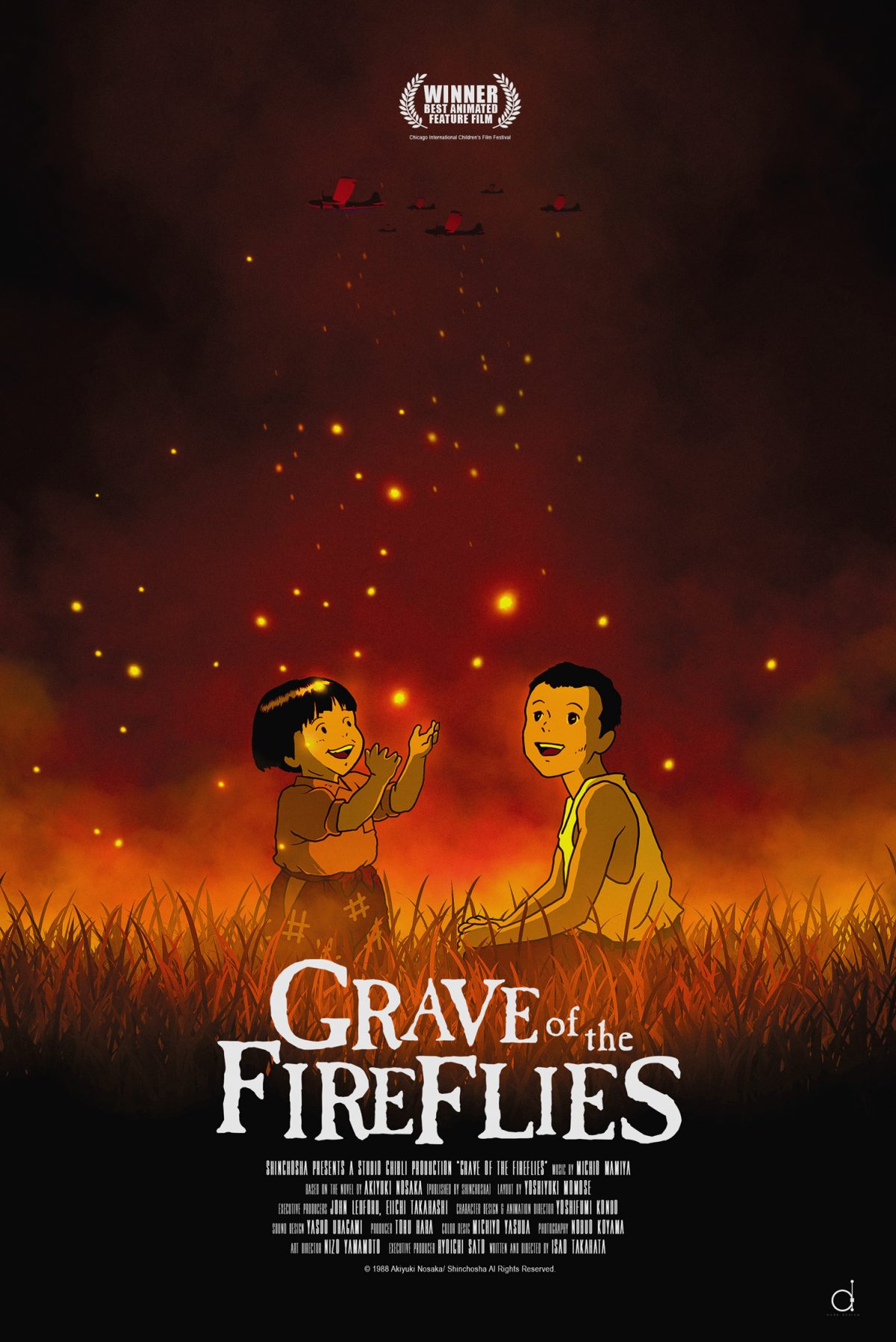

If you’ve seen it once, you probably haven’t seen it twice. Most people can't handle a second viewing. Graveyard of the Fireflies isn't just a "sad movie." It’s an endurance test of the human spirit that leaves a permanent mark on your psyche.

Produced by Studio Ghibli in 1988, it often gets lumped in with whimsical classics like My Neighbor Totoro. That’s a mistake. A massive, devastating mistake. While Totoro celebrates the magic of childhood, this film documents the systematic destruction of it. It’s a brutal, honest, and deeply uncomfortable look at the final months of World War II through the eyes of two siblings, Seita and Setsuko.

Honestly, it’s one of the few films that feels more like an artifact than a piece of entertainment. It’s a ghost story. You know how it ends from the very first scene—Seita dying alone in a train station—and yet, you spend the next 89 minutes desperately hoping for a different outcome.

The True Story Behind Graveyard of the Fireflies

A lot of viewers assume this is just a fictional tear-jerker. It’s not. The movie is based on the 1967 semi-autobiographical short story by Akiyuki Nosaka.

Nosaka lived through the 1945 firebombing of Kobe. He lost his father. He lost his sisters to malnutrition. Most importantly, he lived with a crushing sense of survivor's guilt for the rest of his life. In real life, Nosaka’s sister died of starvation, and he often blamed himself for her death, admitting that he sometimes ate food that should have gone to her. Writing the story was his way of apologizing to her.

Director Isao Takahata took that raw, bleeding guilt and put it on screen. Takahata himself was a survivor of the air raids; he once recalled running through the streets in his pajamas with his sister during an attack. This isn't "history" to the creators. It was memory.

Why the "Anti-War" Label Doesn't Quite Fit

You’ll hear people call this the greatest anti-war movie ever made. Interestingly, Takahata himself actually disagreed with that.

He didn't set out to make a political statement about the ethics of the firebombing of Kobe or the morality of the Pacific War. Instead, he wanted to show the isolation of youth. He was fascinated (and disturbed) by how Seita, the teenage protagonist, chooses to retreat from society rather than endure the humiliations of living with his aunt.

📖 Related: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Seita is proud. Too proud. When his aunt becomes resentful of feeding two extra mouths during a famine, Seita decides they can make it on their own in an abandoned bomb shelter.

It’s a fatal error.

Takahata’s point was that when a society breaks down, the youngest among us—those who should be the most protected—are the first to fall through the cracks because of their lack of experience and the pride of youth. It’s a critique of social isolation as much as it is a critique of war.

The Animation of Empty Space

There’s a concept in Japanese filmmaking called ma. It basically translates to "emptiness" or "the space between."

Studio Ghibli is famous for this. In Graveyard of the Fireflies, ma is used to devastating effect. The movie lingers on shots of a rusted tin of fruit drops, the still water of a lake, or the way the light filters through the trees. These moments of stillness make the violence of the firebombing feel even more jarring.

The firebombing sequence itself is terrifying because it isn't "action." It’s chaos. The B-29 Superfortresses aren't shown as villains; they are shown as impersonal machines dropping canisters of napalm that turn a neighborhood into an oven in seconds.

There’s a specific detail many miss: the color of the fire. In most anime of that era, fire was painted with bright reds and oranges. Takahata insisted on using a more realistic, brownish-red hue to mimic the look of actual incendiary chemicals burning. It’s that level of commitment to reality that makes the movie feel so heavy.

👉 See also: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

The Symbolism of the Fruit Drops

If you’ve seen the film, you can’t look at a tin of Sakuma drops without feeling a knot in your stomach.

The tin starts as a symbol of comfort. It represents the "normal" world that Seita is trying to maintain for his four-year-old sister, Setsuko. When the candy runs out, he fills the tin with water to get the last bit of sugar. Eventually, the tin becomes a funerary urn.

It’s a masterclass in visual storytelling. The transition from a treat to a vessel for ashes mirrors the total collapse of their lives.

Why the Aunt Isn't the True Villain

It’s easy to hate the aunt. She’s cold, she’s selfish, and she’s mean to a couple of orphans. But if you look closer, she’s a product of a desperate environment.

Japan in 1945 was starving. People were trading precious silk kimonos for a few cups of rice. The aunt is trying to keep her own family alive. From her perspective, Seita is a lazy teenager who doesn't help with the war effort but expects to be fed.

The tragedy isn't that she’s "evil." The tragedy is that the war turned survival into a zero-sum game. For one person to eat, another had to starve.

The Cultural Impact and Modern Relevance

When the movie was first released in Japan, it was actually a double feature. Can you imagine? It played alongside My Neighbor Totoro.

✨ Don't miss: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

Audiences would watch the whimsical forest spirits and then be hit with the slow-motion death of two children. Or worse, they’d watch the tragedy first and try to recover with the giant cat-bus. It was a box office struggle because, understandably, parents weren't sure what to make of it.

Over time, however, its reputation grew. It’s now cited by critics like Roger Ebert as one of the most powerful films ever made. Ebert once wrote, "It belongs on any list of the greatest war movies."

In 2026, the film’s themes of displaced refugees and the civilian cost of conflict feel uncomfortably modern. We see these same images on the news daily. The movie reminds us that "collateral damage" has a face, and usually, it’s a small one.

Misconceptions You Should Stop Believing

There are a few "theories" floating around the internet that just don't hold water when you look at the facts.

- The movie is a critique of the U.S. military. Not really. While the bombs come from American planes, the film focuses almost entirely on the Japanese domestic experience and the failure of their own local systems to support their citizens.

- It was meant for children. No. While it’s animated, Ghibli and Takahata were targeting an adult audience capable of processing the historical context and the grim reality of the ending.

- The fireflies are just for aesthetics. The fireflies are a metaphor for the kamikaze pilots—short-lived, beautiful, and doomed—as well as the incendiary bombs themselves. They represent the fragility of life.

How to Approach a First-Time Viewing

If you haven't seen it yet, don't go in expecting a standard "sad movie" experience. You need to be in the right headspace.

- Watch the original Japanese audio with subtitles. The voice acting for Setsuko was done by a five-year-old girl (Ayano Shiraishi), and the raw, unpolished nature of her performance is what makes the character so heartbreakingly real.

- Pay attention to the color palette. Notice how the "ghost" versions of Seita and Setsuko are bathed in a harsh, unnatural red light, contrasting with the muted, dusty browns of the living world.

- Keep tissues nearby. This isn't a suggestion; it’s a requirement.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Historians

If the film moved you, the best way to process it is to look into the actual history of the Kobe firebombings. Understanding the scale of the destruction—over 8,000 people killed in a single day—contextualizes Seita's desperation.

You can also read Akiyuki Nosaka’s original story. It provides even more insight into the guilt that fueled the narrative. Seeing how the author processed his trauma through fiction adds a layer of depth to every scene in the film.

Finally, explore Isao Takahata’s other works, like The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. He was a director who refused to simplify human emotions. He believed that animation could handle the heaviest truths of our existence, and Graveyard of the Fireflies is the ultimate proof of that.

The movie doesn't offer a happy ending because the survivors didn't get one. It offers something better: the truth. It forces us to look at the cost of pride and the reality of war without blinking. That’s why it’s essential viewing, even if you only ever watch it once.