You've probably seen it a million times in algebra class. That sharp, pointy "V" sitting right on the origin. It looks simple. It looks predictable. But honestly, the graph of absolute value is where a lot of people start losing their grip on functions because they treat it like a static picture rather than a dynamic transformation.

Math isn't just about drawing lines. It’s about logic.

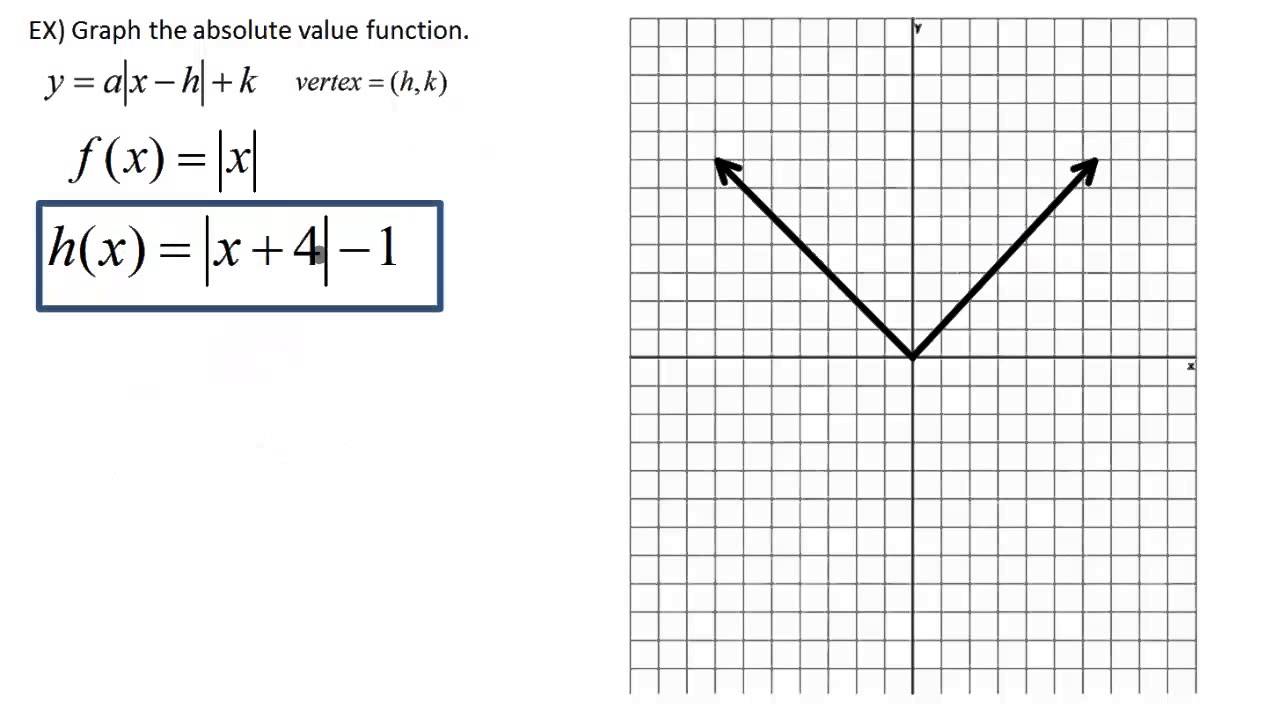

The absolute value function, usually written as $f(x) = |x|$, is basically a "positivity machine." It takes whatever you give it and strips away the negative sign. If you feed it a 5, you get a 5. If you feed it a -5, you still get a 5. This creates a geometric reflection that forces the graph to bounce off the x-axis.

Think about it.

👉 See also: Fixing The Mac Recovery Server Could Not Be Contacted Error Once And For All

The "V" Shape Isn't Just for Show

Why a V? Why not a curve or a circle? It comes down to the piecewise nature of the function. An absolute value graph is actually two linear equations masquerading as one. On the right side of the y-axis, where $x$ is positive, you’re just graphing $y = x$. On the left side, where $x$ is negative, you’re graphing $y = -x$.

The point where these two lines meet is called the vertex.

In the parent function $y = |x|$, that vertex is at $(0,0)$. But things get weird—and way more interesting—when you start messing with the numbers inside and outside those vertical bars. You’ve probably heard teachers talk about "h" and "k" values. They’re usually referring to the vertex form: $y = a|x - h| + k$.

Most people mess up the "h" value. They see $|x - 3|$ and think the graph should move to the left because, hey, three is negative, right? Nope. It moves to the right. It’s counterintuitive. It’s annoying. But it’s how the logic of horizontal shifts works in almost every function in mathematics, from parabolas to sinusoids.

How Transformations Actually Work (And Why They Break)

When you add a number outside the bars, the graph moves up or down. That’s easy. Everyone gets that. If you have $y = |x| + 4$, the whole V just slides up four units. Easy money.

But let's talk about the "a" value—the number multiplying the absolute value. This is the "stretch" or "compression." If $a$ is 2, the V gets narrower, like it’s being squeezed. If $a$ is 0.5, it gets wider.

And if $a$ is negative?

The whole thing flips upside down. Now you have a mountain instead of a valley.

I remember a student once asking me why we couldn't just have a horizontal V. Well, you can, but then it’s no longer a function. It wouldn't pass the vertical line test. For every $x$, you'd have two $y$ values, and in the world of standard functions, that's a big no-no.

The Real-World Connection: It’s Not Just Homework

You might think the graph of absolute value only exists to torture high schoolers, but it's actually foundational in data science and engineering. Ever heard of "Mean Absolute Error" (MAE)?

If you're training an AI model—kinda like the ones we use every day—you need to measure how far off your predictions are. You can't just average the errors, because the positive and negative errors would cancel each other out. You'd end up thinking your model is perfect when it’s actually a disaster.

So, you take the absolute value of the errors.

The graph of those errors looks like a series of absolute value functions. It creates a "penalty" that grows linearly. In finance, traders use these graphs to calculate "drawdowns" or the distance from a peak to a trough in a stock’s price. It’s all about distance, and distance is never negative.

The Most Common Mistakes You’re Probably Making

The Negative Sign Trap: People see $y = -|x + 2|$ and try to distribute the negative sign into the bars. You can’t do that. Absolute value bars are like a fortress. The negative sign stays outside, reflecting the entire graph over the x-axis after the absolute value has been calculated.

💡 You might also like: ipad 6th generation case: The Truth About What Actually Fits

The Slope Confusion: The slope of the right side of $y = a|x - h| + k$ is just $a$. The slope of the left side is $-a$. If you know that, you don't even need to plot points. You just find the vertex and use the slope like a staircase.

Domain and Range: The domain of an absolute value function is almost always "all real numbers." You can plug in anything. But the range? That’s limited. If the V opens up, the range starts at the y-value of the vertex and goes to infinity. If it opens down, it goes from negative infinity up to the vertex.

Advanced Tweaks: What Happens Inside the Bars?

Most textbooks gloss over what happens when you put a coefficient inside the bars, like $y = |2x|$.

Technically, this is a horizontal compression. But because of the properties of absolute value, $|2x|$ is exactly the same as $2|x|$. The horizontal compression looks identical to a vertical stretch. This is one of those rare moments in math where two different transformations yield the exact same visual result.

However, if you have $y = |-x|$, something cool happens. The graph doesn't change at all. Why? Because reflecting a V-shape across the y-axis just lands it right back on itself. It’s a symmetric function.

Step-by-Step: How to Graph Any Absolute Value Equation

Don't overthink it. Seriously.

First, find the vertex. If your equation is $y = |x - 5| + 2$, your vertex is at $(5, 2)$. Just remember that the number inside the bars $(h)$ has its sign flipped, while the number outside $(k)$ stays the same.

Second, look at the leading coefficient. If there's no number there, it's an invisible 1.

Third, plot your vertex. From there, use your "slope" to go up 1 and over 1 to the right, and then up 1 and over 1 to the left. Boom. You have your V.

If you’re dealing with a more complex version, like $y = \frac{1}{2}|x + 1| - 3$, you start at $(-1, -3)$. Then you go up 1 and right 2, and up 1 and left 2.

It's basically just graphing two rays.

The Intersection of Absolute Value and Linear Inequalities

Sometimes you aren't just graphing a line; you're graphing a region.

If you see $y > |x|$, you aren't just drawing the V. You're shading everything inside the V. It’s like a spotlight shining up into the night sky. If it’s $y < |x|$, you’re shading everything underneath it.

📖 Related: Does Apple Music Have a Student Discount? The 2026 Reality Check

This gets used in manufacturing tolerances. If a part needs to be $10cm$ long with a tolerance of $0.1cm$, the equation is $|x - 10| \leq 0.1$. The graph of this on a number line is a segment, but in a 2D coordinate plane, it defines a specific "safe zone" for production.

Why This Matters for Your Next Exam (or Job)

Understanding the graph of absolute value is a litmus test for whether you understand how functions move. If you can master the shifts and stretches here, you’ll find that quadratic functions, square root functions, and even complex trigonometric graphs follow the exact same rules.

It’s all the same logic.

Once you see the pattern, you stop memorizing and start seeing.

Actionable Next Steps to Master Absolute Value Graphs

- Practice the "Inside-Out" Rule: Whenever you see a horizontal shift inside the bars, physically point in the opposite direction of the sign. It sounds silly, but it builds the muscle memory needed to avoid the most common error in coordinate geometry.

- Test the Vertex: Before you finish any graph, plug the x-coordinate of your vertex back into the original equation. If the result doesn't match your y-coordinate, you've made a sign error.

- Use Desmos for Instant Feedback: Open a graphing calculator and type in $y = a|x - h| + k$. Add "sliders" for $a, h,$ and $k$. Move them around. Watch how the V dances across the screen. Seeing the graph move in real-time is worth more than reading a hundred textbooks.

- Identify the Range First: Before drawing, look at the "k" value and the sign of "a". This tells you immediately where your graph lives on the y-axis, preventing you from drawing a V that goes off the edge of your paper.