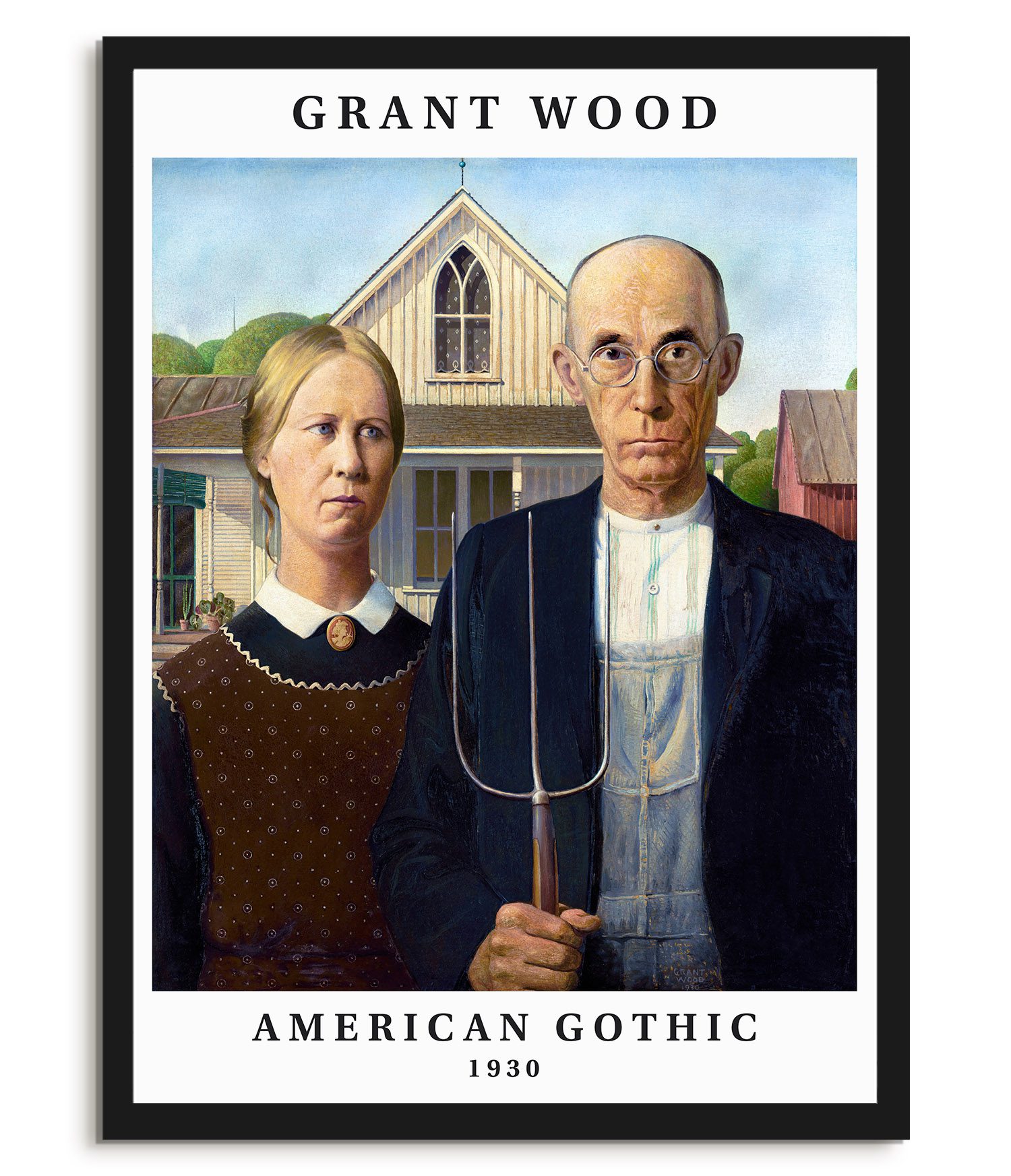

You know the painting. Everyone does. That stern couple—the pitchfork-wielding farmer and his daughter (or is it his wife?) standing in front of a white house with a weirdly pointy window. It’s been parodied by everything from The Muppets to The Simpsons. But Grant Wood, the American painter who created it, wasn't just some country bumpkin with a brush. Honestly, he was a bit of a rebel in overalls.

He spent his life in Iowa, yet he studied in Europe. He lived in a hayloft, but he was obsessed with the precision of 15th-century Flemish masters. People often pigeonhole him as a simple "Regionalist," someone who just painted the "good old days" of the Midwest. That’s basically a massive oversimplification. If you look closer at his work, there’s a strange, almost eerie stillness. It’s not just "pastoral." It’s unsettling. It’s deliberate. It’s Grant Wood.

The Secret Life of a Cedar Rapids Bohemian

Wood was born on a farm near Anamosa, Iowa, in 1891. That’s the "origin story" everyone loves, but his path to becoming a world-famous artist wasn't a straight line from the cornfield to the gallery. After his father died, the family moved to Cedar Rapids. He was a skinny kid who loved making things. He wasn't just "born to paint." He worked at a metal shop. He made jewelry. He even did some interior design.

The thing is, he went to Europe four times. Let that sink in. In the 1920s, a guy from Iowa was trekking to Paris and Munich to see what the "moderns" were doing. He tried the Impressionist style—lots of blurry light and soft edges. You can actually find his early sketches, and they look nothing like the crisp, sharp Grant Wood we know today. He was searching. He was trying to find a voice that didn't sound like a cheap imitation of a Frenchman.

Then, he went to Munich in 1928. He saw the work of Jan van Eyck and Hans Memling. These guys painted every single wrinkle, every blade of grass, and every thread in a cloak with terrifying detail. It clicked. He realized he didn't need to paint like a Parisian to be a great artist. He needed to paint Iowa with the same obsessive clarity the Old Masters used for saints and kings.

Why American Gothic Isn't What You Think

Okay, let's talk about the elephant in the room: American Gothic. When this thing debuted at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1930, Iowans were actually pretty pissed off. They thought Wood was making fun of them. They saw "pinched-faced" fanatics. One farmwife supposedly threatened to bite his ear off.

🔗 Read more: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

But look at the models. The man is Wood’s dentist, Dr. Byron McKeeby. The woman is Wood’s sister, Nan. They aren't even a couple; Wood intended them to be father and daughter. He had them pose separately. He found the house first—the Dibble House in Eldon, Iowa—and thought the "Carpenter Gothic" window was hilarious and out of place on such a tiny home.

The painting isn't a snapshot. It's a construction. Wood was interested in the idea of "survivability." He painted it during the Great Depression. While the rest of the world was falling apart, he wanted to depict a type of person he thought could weather any storm. Hard. Rigid. Unyielding. Whether that’s a compliment or a critique is still something art historians argue about over coffee.

The Regionalist Rebellion

Grant Wood, along with Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry, formed the "Regionalist" trio. They were the "anti-New York" squad. They hated the way the art world was pivoting toward total abstraction—blobs and lines that didn't "mean" anything to the average person. Wood wanted art that people in Des Moines could understand and appreciate.

He once said, "All the good ideas I’ve ever had came to me while I was milking a cow."

Now, was that true? Probably not entirely. Wood was a master of self-branding. He often wore denim overalls to public events, even though he was a sophisticated, well-traveled man. He knew that the "honest Midwesterner" persona sold paintings. He was playing a character as much as he was painting one.

💡 You might also like: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

The Weird, Dreamlike Quality of the Iowa Landscape

If you look at his landscapes, like Young Corn or Fall Plowing, they don't look like real photos. The trees look like green marshmallows. The hills are perfectly round, like loaves of bread rising in an oven. There’s no dirt. There’s no chaos.

This is where Wood gets interesting. He wasn't painting the Iowa he saw out his window in 1935. He was painting a memory. A myth. It’s a "dream Iowa." Some critics call it "Magic Realism" before that was even a popular term. Everything is too clean. Too orderly. It feels like if you stepped into the painting, the grass would feel like velvet and the air would smell like fresh laundry.

There’s a tension there. It’s peaceful, sure, but it’s also a little claustrophobic. You’ve got these rolling hills that seem to go on forever, but they’re fenced in. Everything is managed. Everything is under control. It reflects Wood’s own life—a man who lived with his mother for most of his adult life and kept his private world very, very private.

The Complicated Legacy of a Public Icon

Grant Wood died young, just before his 51st birthday, of pancreatic cancer. In his final years, he was actually under a lot of pressure. He was a professor at the University of Iowa, and things got ugly. There were rumors and accusations about his personal life—specifically his sexuality—which was a dangerous topic in the 1940s. Some colleagues tried to push him out. The "simple farmer" image was cracking.

Because of this, some modern scholars look at his work through a different lens. When you see those rigid figures and those hidden meanings, you start to wonder what he was hiding. Is American Gothic a satire? A tribute? A self-portrait of repression?

📖 Related: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

It’s probably all of them.

Real Examples of Wood’s Range

- The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere (1931): This one looks like a toy set. It’s quirky and almost funny. It shows Wood didn't take history too seriously.

- Daughters of Revolution (1932): This is Wood being snarky. He painted three elderly women looking very smug in front of a painting of George Washington crossing the Delaware. It was his way of poking fun at people who were obsessed with their "pedigree" but lacked actual substance.

- Parson Weems' Fable (1939): He shows the story of George Washington and the cherry tree, but he puts a grown man’s head on the child’s body. It’s surreal and bizarre.

How to Appreciate Wood Today

If you want to actually "get" Grant Wood, you can't just look at a JPEG on your phone. You have to see the brushwork. He used a technique called glazing, where he’d lay down thin, transparent layers of oil paint. That’s why his paintings seem to glow from the inside.

A lot of people think he's "dated." They think his work belongs in a dusty hallway. But in an era of AI-generated art and digital perfection, Wood’s hand-painted, obsessive precision feels more human than ever. He was trying to find something permanent in a world that was changing way too fast. We’re kind of doing the same thing now, aren't we?

Step-by-Step Guide to Exploring Grant Wood’s Work

- Visit the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art. They have the largest collection of his work, including his "5 Turner Alley" studio where he lived and worked. You can literally see the bathtub he hid under a trapdoor.

- Look for the "Easter Eggs." In his landscapes, look for the patterns in the crops. He often painted them to look like stitching or fabric patterns, a nod to his mother's sewing.

- Read "Grant Wood: A Life" by R. Tripp Evans. If you want the "unfiltered" version of his life, this is the book. It dives into the controversies and the psychological depth behind the paintings.

- Compare him to the "New Objectivity" movement. Look up German painters from the 1920s like Otto Dix or Christian Schad. You’ll see exactly where Wood got his "hard-edge" inspiration from, and it’ll change how you see his "simple" American scenes.

- Check out the Dibble House in Eldon, Iowa. It’s a real place. Standing where Wood stood gives you a weird perspective on how he distorted reality to fit his vision. It’s smaller than it looks in the painting. Way smaller.