When Good Times first hit CBS in 1974, it wasn't supposed to be a cartoon. It was heavy. You had Florida and James Evans trying to raise three kids in a Chicago housing project while the world basically tried to crush them. It was the first time we really saw a Black nuclear family on a sitcom, dealing with real-world grit—rent parties, gang recruitment, and the kind of poverty that doesn't just go away in thirty minutes.

Then came J.J. Evans.

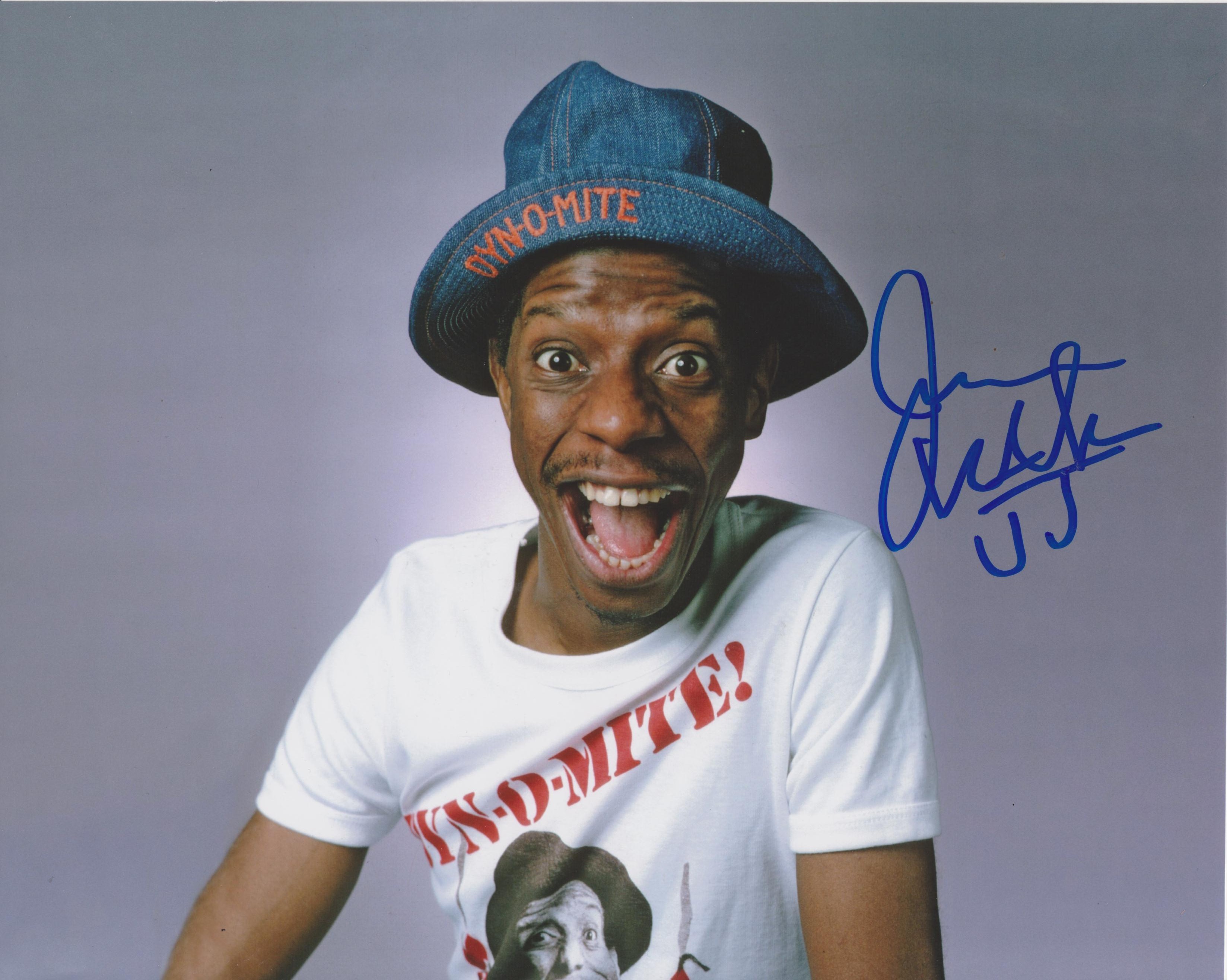

Pretty soon, the social commentary started taking a backseat to a skinny kid in a floppy hat yelling "Dyn-o-mite!" It’s one of the most famous pivots in TV history. Honestly, it's also one of the most controversial. While the ratings went through the roof, the show's soul started to fracture.

How J.J. Evans Changed the Script (Literally)

Jimmie Walker wasn't even the lead when the show started. He was the goofy older brother to the "socially conscious" Michael and the bright, ambitious Thelma. But you can't fight the audience. By the end of the first season, J.J. was a certified phenomenon.

He was everywhere.

Lunchboxes, posters, comedy albums—Jimmie Walker became the face of 1970s television. But behind the scenes? Things were getting ugly. John Amos (James) and Esther Rolle (Florida) were purists. They wanted a show that reflected Black excellence and struggle. Instead, they felt like they were watching their "son" turn into a 20th-century version of a minstrel act.

The "Dyn-o-mite" Origin Story

Funny enough, Jimmie Walker wasn't even the one who wanted the catchphrase. It was director John Rich who pushed for it. He basically forced Walker to say it at the end of an episode called "Black Jesus" in Season 1.

🔗 Read more: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

Walker hated it. Norman Lear, the legendary producer, hated it.

But it worked.

The crowd went nuts. Eventually, Rich insisted Walker say it at least once every single episode. It became the show's "Bazinga" or "Whatchu talkin' 'bout, Willis?" but with a much sharper edge for the people actually making the show.

The Feud That Killed James Evans

If you’ve ever wondered why the show suddenly killed off the dad in Season 4, look no further than the "J.J. Problem." John Amos didn't hold back. He openly criticized the writers—none of whom were Black at the time—for making J.J. less of a talented artist and more of a "buffoon."

Amos argued that having an illiterate, girl-crazy, unemployed 18-year-old as the hero of the show sent a terrible message. He felt the show was betraying the Black community.

The producers got tired of the complaining.

💡 You might also like: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Instead of fixing the character, they fired the father. The moment Florida finds out James died in a car accident in Mississippi remains one of the most gut-wrenching scenes in TV history, but it was born out of a nasty contract dispute and creative ego.

Why Esther Rolle Left

Esther Rolle was even more vocal. She famously told Ebony magazine in 1975 that J.J. was "more stupid" every week. She hated that he wore a hat in the house and acted like a "giant bird" with his arms outstretched.

She eventually walked away after Season 4 because she couldn't stand the direction of the scripts. Think about that: the star of the show quit her own hit series because she thought the "Dyn-o-mite" kid was ruining the culture. She only came back for the final season after they promised to make J.J. a bit more responsible.

Jimmie Walker’s Side of the Story

It’s easy to make Jimmie Walker the villain here, but he was just a young comic doing his job. He’s admitted in interviews with the Television Academy that he didn't really have a relationship with Amos or Rolle. He said they "never talked" and "were never friends."

He was a stand-up at heart. He saw the show as a gig.

While his co-stars were worried about the sociological impact of the Evans family, Walker was focused on the comedy. He once noted that the show probably could have lasted ten years if the cast had actually liked each other. Instead, it was a "bunker mentality" where nobody spoke between takes.

📖 Related: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

The Lasting Legacy of J.J. Evans

Despite all the drama, J.J. Evans changed the way networks looked at "breakout" stars. He was the prototype for characters like Steve Urkel. He proved that a secondary character could hijack a show if they had enough charisma and a catchy enough phrase.

Was J.J. a stereotype? Many people still say yes. But he was also a talented painter. That's a detail people often forget. The paintings J.J. "created" on the show were actually the work of real-life artist Ernie Barnes (the most famous being The Sugar Shack).

There was a depth there that sometimes got buried under the "Dyn-o-mite" shouting.

Key Takeaways for Fans and TV Buffs

If you're revisiting the show or just curious about why it still matters, here's what you should keep in mind:

- Watch the early seasons: If you want to see the show the way Rolle and Amos intended, Season 1 and 2 are where the social realism is strongest.

- The "Urkel" Effect: Look at how the show shifts focus. It’s a masterclass in how network TV chases ratings at the expense of its original premise.

- The Art is Real: Pay attention to J.J.'s paintings. They are legit pieces of art history that provided a window into Black life, even when the dialogue didn't.

- Politics Matter: The tension between the "actor" (Walker) and the "activists" (Rolle/Amos) is a recurring theme in Black Hollywood history. It didn't start or end with Good Times.

Next time you see a clip of J.J. Evans strutting across the screen, remember that those laughs came with a massive price tag for the people on set. It wasn't always "Good Times" behind the camera.

You can actually track the shift yourself by watching the Season 1 episode "Black Jesus" and comparing it to anything from Season 5. The difference in tone isn't just a shift in writing—it's a completely different philosophy of what Black television was allowed to be.