Let's be honest. Most "strategy" meetings are just expensive therapy sessions where people shout buzzwords at a whiteboard. You've been there. I've been there. We talk about "innovation," "synergy," and "becoming the industry leader," and then we wonder why nothing actually changes on Monday morning. Richard Rumelt noticed this too. He’s a professor at UCLA Anderson and a consultant who has seen the inside of more boardrooms than most of us have seen coffee shops. In his seminal work, the Good Strategy Bad Strategy book, Rumelt basically calls out the entire corporate world for being addicted to fluff.

He’s not being mean. He’s being precise.

The central problem is that we’ve confused strategy with ambition. If you ask a CEO what their strategy is and they say, "We want to grow revenue by 20%," they haven't given you a strategy. They’ve given you a goal. That’s like a football coach saying his strategy for the Super Bowl is "to score more points." No kidding, Coach. But how? Strategy is the how. It’s the specific, often painful set of choices you make to overcome a specific obstacle. If there’s no obstacle, you don’t need a strategy; you just need to keep doing what you’re doing.

The Four Horsemen of Bad Strategy

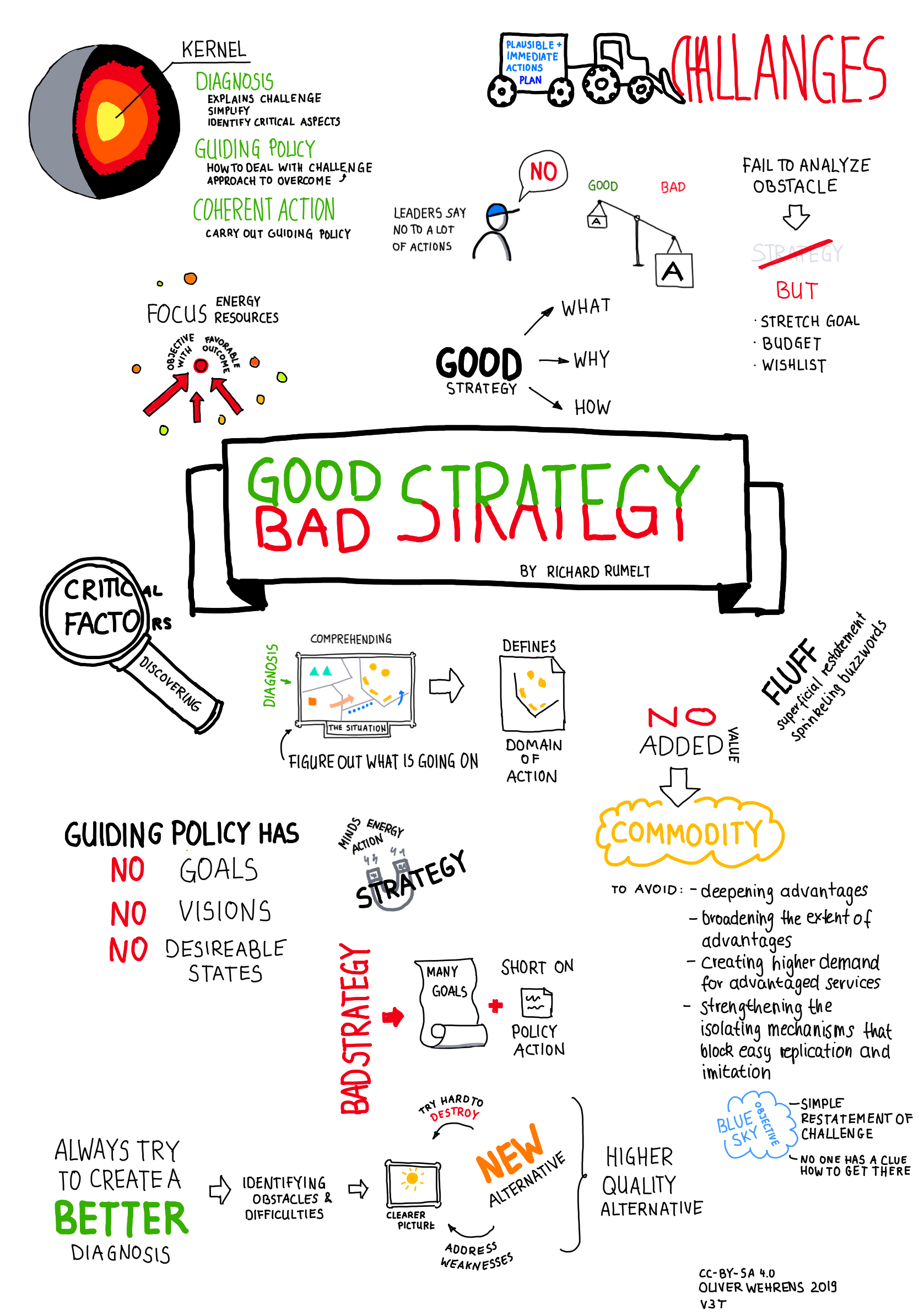

Rumelt doesn't just complain; he categorizes. He identifies four hallmarks of what he calls "Bad Strategy." It’s a bit of a reality check.

First, there’s Fluff. This is the high-level gibberish that sounds important but means absolutely nothing. It’s using words like "integrated ecosystem" or "customer-centric paradigm shift" to hide the fact that you have no idea what to do next. It’s a linguistic mask for a lack of thought.

Then comes the Failure to Face the Challenge. You can’t have a strategy if you haven't defined the problem. Rumelt uses the example of International Harvester in the late 70s. They had a "strategy" that was just a bunch of financial targets. What they didn't address was their horrific labor relations and an inefficient manufacturing process that was eating them alive. Because they didn't define the problem, the strategy was just a wish list.

Mistaking Goals for Strategy is the third one. This is the big one. We see it everywhere. High-level goals are just "stretch targets." They don't tell you how to get there. They just tell you where you’d like to be if magic were real.

Finally, there’s Bad Strategic Objectives. This happens when a leader tries to do everything at once. They have 20 "priority" initiatives. If you have 20 priorities, you have zero priorities. A good objective is a bridge between the challenge and the action. If it’s just a list of chores, it’s not strategic.

💡 You might also like: Big Lots in Potsdam NY: What Really Happened to Our Store

What Actually Makes a Strategy "Good"?

The Good Strategy Bad Strategy book introduces a concept Rumelt calls "The Kernel." It’s remarkably simple, which is why it’s so hard for people to actually do. The Kernel has three parts:

- A Diagnosis: An explanation of the nature of the challenge. A great diagnosis simplifies the world by identifying certain aspects of the situation as critical.

- A Guiding Policy: An overall approach chosen to cope with or overcome the obstacles identified in the diagnosis.

- Coherent Actions: Steps that are coordinated with one another to support the guiding policy.

Think about a doctor. You go in with a pain in your side. The doctor doesn't say, "My strategy is for you to feel 100% better by Tuesday." That’s a goal. Instead, the doctor does a diagnosis (you have appendicitis). They set a guiding policy (we need to remove the appendix immediately). Then they take coherent actions (prep the OR, administer anesthesia, perform the surgery).

Every step follows the one before it. If the doctor just gave you a pep talk about wellness, you'd die. Yet, in business, we give pep talks and call them "strategic plans" all the time.

Leveraging Power (The David and Goliath Factor)

Strategy is about leverage. Rumelt talks a lot about finding "pivots." This isn't the Silicon Valley "pivot" where you change your app from a dog-walking service to a crypto exchange. This is about finding a point where a small amount of effort creates a massive result.

Take the classic example of David and Goliath. Goliath was a beast. In a straight-up wrestling match, David is a smear on the ground. That’s the "challenge." David’s diagnosis was that Goliath’s size made him slow and that his armor left his forehead exposed. His guiding policy was to avoid close-range combat and use distance. His coherent action was using a sling—a weapon he was actually an expert with—to hit the one spot Goliath hadn't protected.

David didn't try to be a better giant than the giant. He changed the game.

In the Good Strategy Bad Strategy book, Rumelt highlights how Apple did this in the late 90s. When Steve Jobs returned in 1997, Apple was weeks away from bankruptcy. Most people thought they needed to release ten new products. Jobs did the opposite. He cut 70% of the product line. He focused on just four computers. That was a "coherent action" that moved the needle because it solved the immediate problem: bleeding cash on garbage products nobody wanted.

📖 Related: Why 425 Market Street San Francisco California 94105 Stays Relevant in a Remote World

The Problem with Charismatic Leadership

We have this weird obsession with "visionary" leaders. We think if someone is charismatic enough, they can just manifest success through sheer will. Rumelt argues that this is dangerous. "Strategic momentum" is often just a fancy word for "we’re doing well because the market is up."

True strategy is cold and analytical. It requires looking at the world as it is, not as you wish it were. It requires saying "no" to a hundred good ideas so you can say "yes" to the one great one. Honestly, most people hate doing this. It’s socially awkward to tell a department head that their pet project is being cut because it doesn't fit the guiding policy. But that's the job.

Why "Bad Strategy" Is So Popular

You might wonder why, if this is so obvious, bad strategy is everywhere. Why do we keep buying into the fluff?

It’s because good strategy is hard. It requires a level of focus that is physically and emotionally draining. Bad strategy, on the other hand, is easy. It feels good. It’s inclusive. You can give everyone a "strategic objective" so nobody feels left out. You can write a mission statement that sounds like a Hallmark card and everyone can nod and go back to their desks.

Bad strategy avoids the pain of choice. If you choose a specific path, you might be wrong. If you stay vague, you can never be proven wrong. You can just blame "the market" or "unforeseen circumstances" when things go south.

Real-World Nuance: The Case of Nvidia

Look at Nvidia. Long before they were the darlings of the AI boom, they made a strategic choice. Their diagnosis in the mid-2000s was that the world would eventually need massive amounts of parallel processing, not just for games, but for general computing. Their guiding policy was to invest heavily in CUDA, a programming platform that allowed their GPUs to do more than just render pixels.

For years, investors hated this. It was expensive. It didn't have an immediate payoff. But it was a coherent action. When the AI wave finally hit, Nvidia was the only company with the hardware and the software stack ready to go. They didn't just get lucky; they had a strategy that anticipated a specific challenge and focused resources on it for a decade.

👉 See also: Is Today a Holiday for the Stock Market? What You Need to Know Before the Opening Bell

That's the "Good Strategy" Rumelt is talking about. It’s a long-term play based on a fundamental truth about the world.

Practical Steps: How to Fix Your Own Strategy

If you're sitting there realizing your current plan is just a list of hopes and dreams, don't panic. You can fix it. It just takes some intellectual honesty.

First, identify the "Crux." This is Rumelt’s term for the most important part of the challenge that you actually have a chance of winning. Don't try to solve every problem. Find the one that, if solved, makes everything else easier. Ask yourself: "What is the one thing holding us back that we actually have the power to change?"

Second, audit your actions. Look at your calendar and your budget. If you say your strategy is "Quality First," but you're cutting the QA budget to save pennies, you don't have a strategy. You have a lie. Your actions must be coherent. They must support each other.

Third, kill the fluff. Go through your strategy documents. Delete every instance of "best-in-class," "leveraging," and "synergy." If the sentence still makes sense without those words, it might have a sliver of strategy in it. If the sentence disappears, it was fluff.

Fourth, define what you are NOT doing. A good strategy is as much about what you leave out as what you put in. If you can't list three things you’ve decided not to do this year in order to focus on your main goal, you haven't made a choice. And strategy is, at its core, the art of making choices.

Next Steps for You

Start by writing down your "Diagnosis" in one sentence. Not a paragraph. One sentence. If you can’t define the problem that simply, you don’t understand it well enough yet. Once you have that, write one "Guiding Policy"—a broad rule of thumb for how you will deal with that problem. Only then should you start making a to-do list.

Strategy isn't a document you produce once a year for the board. It’s a living, breathing way of looking at the world. It’s about being the person in the room who is brave enough to say, "That’s not a plan, that’s just a wish." Read the Good Strategy Bad Strategy book if you want the full, unvarnished truth, but in the meantime, stop dreaming and start diagnosing.

The most successful people aren't the ones with the biggest visions. They’re the ones who understand their obstacles the best.