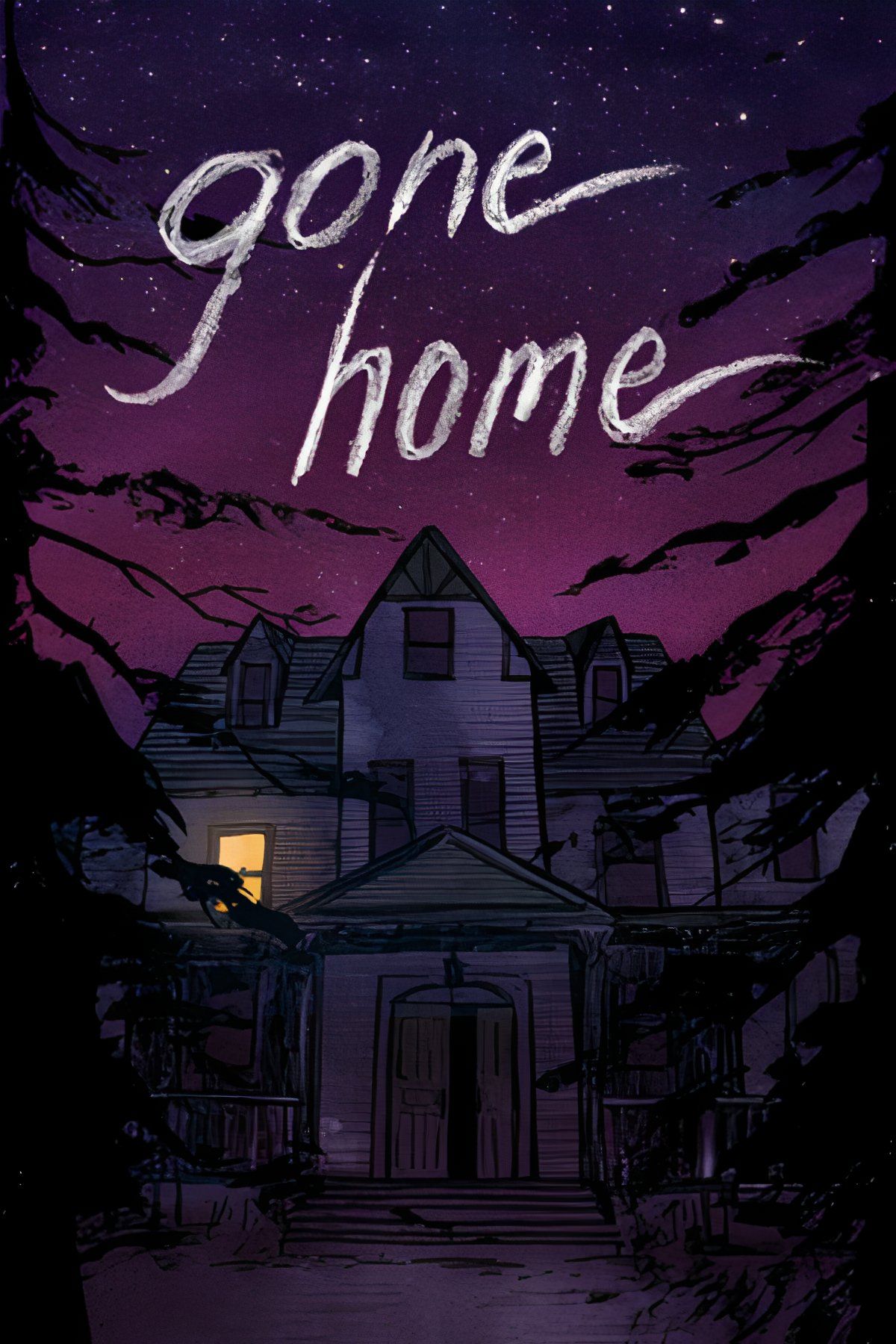

It is June 7, 1995. You are Katie Greenbriar. You’ve just spent a year backpacking through Europe, and you’ve finally arrived at 1 Arbor Hill in the middle of a thunderstorm. The porch light is flickering. A note from your sister, Sam, is taped to the front door, practically begging you not to look for her. Inside, the house is cavernous and empty. This is the setup for Gone Home, a game that, when it released in 2013, fundamentally broke the way we talk about video games. Honestly, it’s still breaking it.

If you weren’t there for the launch, it’s hard to describe the sheer level of vitriol this game inspired. One side of the internet called it a masterpiece of environmental storytelling; the other side screamed that it wasn't even a game because you don't shoot anything. Basically, it became the poster child for the "walking simulator" genre. People felt cheated by the marketing. They expected a horror game—the creaky floorboards and flickering lights certainly suggest a ghost story—but what they got instead was a deeply intimate family drama about growing up, coming out, and the quiet tragedies of suburban life. It was a bait-and-switch. But for many, it was the best bait-and-switch in history.

The Haunting of Arbor Hill is All in Your Head

Most horror games use the "spooky house" trope to hide monsters in the closets. The Fullbright Company, the small team behind Gone Home, used it to hide a diary. As you wander through the house, you aren't looking for ammunition. You're looking for crumpled-up napkins, cassette tapes, and report cards. Steve Gaynor, one of the founders of Fullbright, previously worked on BioShock 2: Minerva's Den, and you can see that DNA everywhere. It’s that same "investigative" feeling, but stripped of the combat.

The brilliance of the game lies in its atmosphere. It weaponizes your expectations. Because it’s dark and there's a storm outside, you spend the first twenty minutes hunched over, expecting a jump scare. You see a red stain on the floor—is it blood? No, it’s hair dye. You find a Ouija board in the basement and think, Okay, here come the demons. But the only demons in this house are the ones the Greenbriar family is dealing with: a father whose writing career is failing, a mother struggling with a mid-life temptation, and a younger sister falling in love for the first time in a world that wasn't ready for her.

🔗 Read more: Why the GTA Vice City Hotel Room Still Feels Like Home Twenty Years Later

The game is short. You can finish it in about 90 minutes if you linger. If you run, you can do it in ten. This brevity is exactly why some players felt the $20 launch price was a scam. But value in gaming is a weird, subjective thing. Is a ten-hour game you forget immediately worth more than a two-hour experience that stays with you for a decade? For a lot of us, the answer was a resounding yes.

Why the "Walking Simulator" Label Stuck

Before Gone Home, we didn't really have a name for games that prioritized exploration over mechanics. Sure, Dear Esther existed, but it was more of a poem than a game. This was different. You could interact with almost everything. You could pick up a box of pens, rotate it, and put it back. You could turn on every faucet in the house. This tactile nature made the house feel lived-in. It felt like a real place, not a level designed for a player.

The term "walking simulator" was originally a pejorative. It was a way for "hardcore" gamers to dismiss anything that didn't have a win state or a skill ceiling. But the industry changed. Now, developers use the term with pride. Without this game, we probably wouldn't have Firewatch, What Remains of Edith Finch, or The Last of Us Part II’s quieter, more exploratory moments. It proved that "gameplay" doesn't always mean "mechanics." Sometimes, gameplay is just the act of being present in a space.

💡 You might also like: Tony Todd Half-Life: Why the Legend of the Vortigaunt Still Matters

The narrative delivery is handled through Sam’s voice diaries, voiced by Sarah Grayson. They are raw. They sound like a teenager actually talking, not a writer trying to sound like a teenager. As you find specific items, a diary entry triggers. You learn about Sam’s relationship with Lonnie, a girl from her school. You hear about their shared love for "Riot Grrrl" music, their Zines, and their secret world. It’s a very specific slice of the 1990s. If you grew up in that era, the sight of a VHS tape with "X-Files" handwritten on the spine hits like a physical weight.

The Narrative Layering You Might Have Missed

While Sam’s story is the "main" plot, the house tells three other stories simultaneously. This is where the expert writing shines.

- Terry Greenbriar’s Failure: If you look at the letters in the father’s office, you realize he’s a struggling historical fiction writer. He had one big hit, and then... nothing. You find rejection letters. You find a subplot about his own father that hints at a history of trauma. It explains why he’s so distant and why he’s so obsessed with his new book project.

- Janice Greenbriar’s Restlessness: In the laundry room and the bedroom, you find hints that the mother is considering an affair with a colleague. It’s subtle. It’s a postcard here, a schedule there.

- The Ghost of Oscar: There is a "ghost" story, but it’s a human one. The house was inherited from an estranged uncle, Oscar. Through hidden panels and old documents, you piece together that Oscar was likely a victim of the same societal prejudices Sam is facing.

These threads don't resolve in a big boss fight. They just... exist. You finish the game and realize you know this family better than you know some of your real-life neighbors. It’s an exercise in empathy.

📖 Related: Your Network Setting are Blocking Party Chat: How to Actually Fix It

Is It Still Worth Playing in 2026?

Honestly, yeah. Even more so now. In an era of 100-hour open-world games filled with repetitive "busy work," a tight, focused narrative is a relief. It’s a palate cleanser. The graphics, while slightly dated, still hold up because the art direction is so specific. The lighting is still some of the best in the genre.

There’s a section of the gaming community that will never like this game. They’ll always see it as a "non-game." And that’s fine. Not everything is for everyone. But if you care about how stories are told, if you want to see how a physical space can be used as a character, you have to play it. It’s a piece of history.

How to Get the Most Out of Your First Playthrough

Don't use a guide. Just don't. The whole point is the discovery. If you know where Sam is or what happened to her before you start, you’ve robbed yourself of the experience.

- Turn off the lights. This isn't a joke. The game relies heavily on its 1995-midnight-storm aesthetic. Play it in the dark with headphones.

- Read everything. The "game" isn't the walking; the game is the reading. If you skip the notes, you’re just walking through an empty house, and yeah, that is boring.

- Check the settings. There are some great commentary modes available now that feature the developers and the voice actors. Save those for a second run.

- Look for the "hidden" items. There are some very well-hidden safes and panels that flesh out the father’s backstory significantly.

- Pay attention to the music. The "Heavens to Betsy" and "Bratmobile" tracks aren't just background noise. They are the soul of the game’s 90s setting.

The impact of Gone Home isn't in its ending—which is surprisingly hopeful—but in the way it makes you feel like an intruder in your own home. It forces you to confront the fact that we never truly know the people we live with. Everyone has a "hidden" room. Everyone has a diary entry they hope no one finds. That realization is scarier than any ghost Fullbright could have programmed into the basement.

If you find yourself stuck or wondering if you've missed a major plot point, go back to the basement. Most people miss the correspondence between Terry and his publisher that explains the true reason they moved into the house in the first place. It changes the context of the entire family dynamic. Once you've finished the main story, take a moment to look at the "Lights Out" achievement/challenge—it’s a great way to see how well you actually know the layout of the house without the help of the lights.