He’s huge. Honestly, Godzilla shouldn’t even be able to stand up, let alone swim at speeds that outpace a nuclear submarine. Yet, when we talk about Godzilla in the ocean, we aren’t just talking about a big lizard taking a bath. We’re talking about a highly specialized biological anomaly that has defined the character for seventy years.

People think of the city-smashing first. The crumbling skyscrapers. The screaming crowds in Tokyo or San Francisco. But Godzilla is, at his core, a marine animal. If you look at the 1954 original directed by Ishirō Honda, the monster doesn't just appear from nowhere; he’s a relic of the Jurassic period disturbed by underwater hydrogen bomb testing. He’s an aquatic hunter that we forced onto land.

The Biology of an Underwater Apex Predator

How does a creature that weighs 90,000 tons—give or take a few thousand depending on which era of film you’re watching—move so fluidly in the water? It’s not just movie magic. Scientists and creature designers have actually spent decades trying to justify the physics of Godzilla in the ocean.

In the Legendary Pictures "Monsterverse," Godzilla is depicted with gills. Look closely during the 2014 film or King of the Monsters (2019) and you’ll see them fluttering on his neck. This is a massive shift from the Toho versions, which generally implied he just held his breath for a really long time or absorbed oxygen through his skin. The "Legendary" Godzilla uses a massive, crocodilian tail to provide propulsion. It’s powerful. It’s efficient. It’s basically a biological motor that allows him to traverse the Pacific in days.

Then there’s the buoyancy issue.

A creature that dense should sink like a stone. Some theorists suggest his bones are honeycombed like a bird’s, but filled with a lighter-than-water biological gas, or perhaps his nuclear heart generates enough thermal energy to create a localized "Leidenfrost effect" in the water, though that’s getting pretty deep into the weeds of fan theory. Realistically, Godzilla in the ocean works because he functions like a marine iguana scaled up to impossible proportions. He’s sleek when he needs to be.

The Mariana Trench and the Hollow Earth

Where does he go when he’s not knocking over the Golden Gate Bridge? Usually, he’s heading for the deeps. In the 2019 film, we see Godzilla’s "lair," a sunken city that looks suspiciously like Atlantis, located near a massive underwater radioactive vent. This is a key part of the lore: the ocean isn't just a highway for him; it's a gas station. He feeds on the planet's natural radiation found in the Earth's mantle, accessed through deep-sea trenches.

💡 You might also like: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

This brings up a weird point about the "Hollow Earth" theory introduced in recent films. The idea is that there are massive tunnels under the ocean floor that allow Godzilla to travel between continents in hours. It explains how he can be in the Atlantic one day and the South China Sea the next without being spotted by every satellite on the planet.

Why the Navy Can't Stop Godzilla in the Ocean

The ocean is big. Really big. You might think the US Navy or the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force would have an easy time tracking a 300-foot-tall lizard, but the ocean is a nightmare for sonar.

Godzilla’s skin is often described as having the same texture as charcoal or jagged rock. In sonar terms, this makes him a "stealth" monster. The sound waves don't bounce back in a clean "ping"; they scatter. In Shin Godzilla (2016), the Japanese government is basically helpless because the creature keeps evolving and changing its buoyancy and heat signature.

- Thermoclines: These are layers of water where the temperature changes rapidly. Godzilla hides under these layers to reflect sonar signals away from him.

- Acoustic Shadowing: He’s smart. In many movies, he uses the noise of submarine engines or underwater volcanic activity to mask his own movement.

- Pressure Resistance: Godzilla has been shown at depths of over 10,000 meters. No human submarine can survive down there for long, but for him, it’s just a quiet nap spot.

The Environmental Symbolism of the Sea

We can't talk about Godzilla in the ocean without talking about what the ocean represented to post-war Japan. In 1954, the sea was a source of life, but it was also the place where the "black rain" of radioactive fallout came from. The ocean was a victim. When Godzilla rises from the waves, he isn't just an animal; he is the ocean’s resentment.

Later films, like those in the 1970s "Hedorah" era, shifted the focus to pollution. Godzilla fought monsters made of sludge and smog. The ocean became a battlefield for the planet's health. It’s a recurring theme: when humans mess with the water, Godzilla shows up to balance the scales.

Sometimes he’s a protector. Sometimes he’s a literal god. But he is always the sea’s ultimate enforcer.

📖 Related: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

Combat in the Deep: A Different Ballgame

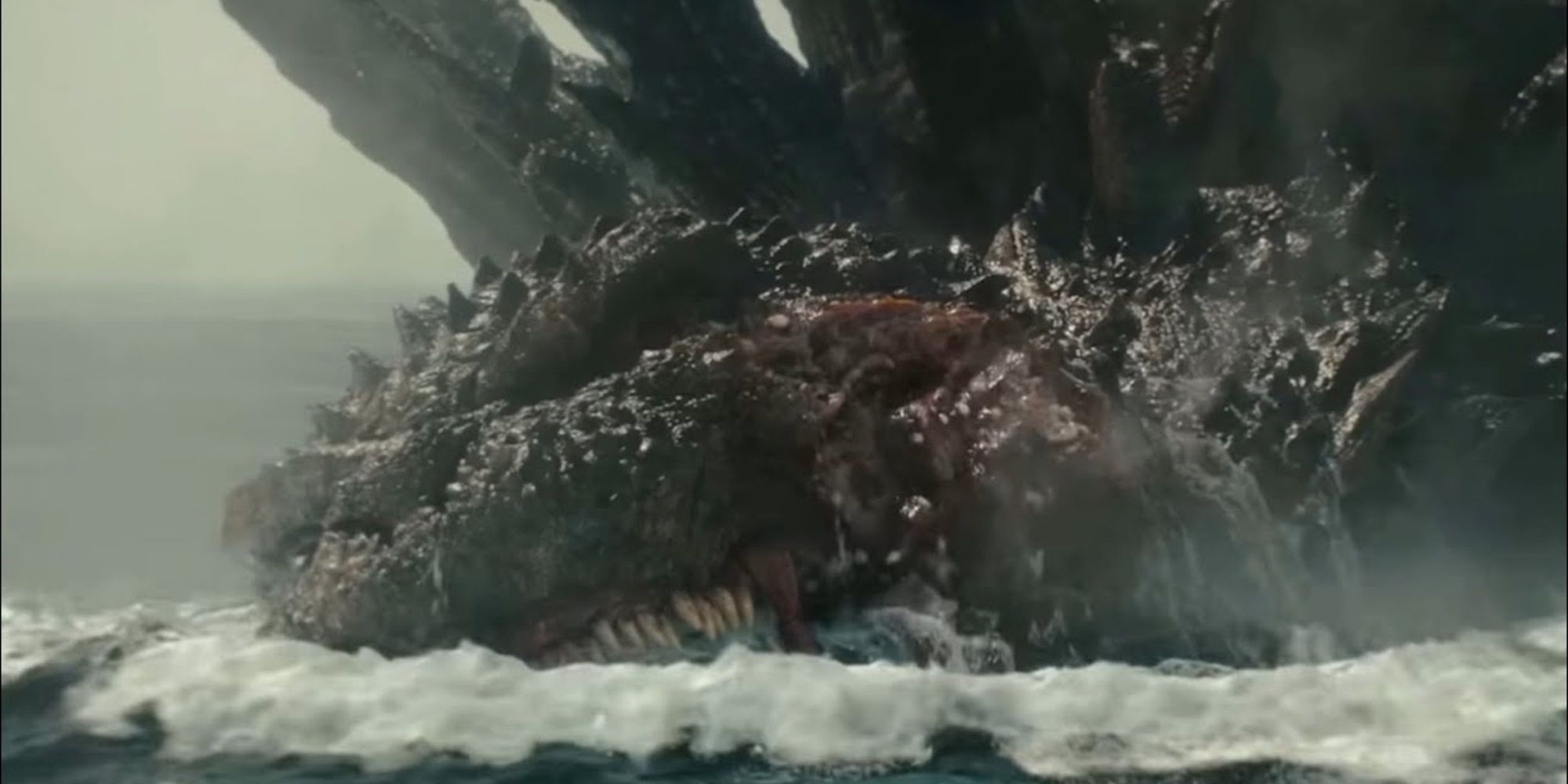

Fighting Godzilla on land is a bad idea. Fighting Godzilla in the ocean is a death sentence. In Godzilla vs. Kong (2021), we see this play out perfectly. On an aircraft carrier, Kong has a fighting chance. He’s fast. He’s got reach. But once they hit the water? It’s over.

Godzilla is a grappler in the water. He uses his weight to drown opponents. He’s got the "home field advantage." Most of his rivals—Ghidorah, Rodan, Kong—are flyers or land-dwellers. They don't have the lung capacity or the hydrodynamic shape to keep up. Godzilla’s atomic breath also behaves differently underwater. Instead of a focused beam of fire, it often becomes a massive thermal shockwave that boils the water around his target.

It’s terrifying.

Think about the sheer amount of energy required to boil a cubic kilometer of seawater in seconds. That’s what’s happening when Godzilla lets loose in the deep.

What People Get Wrong About the "Sea Monster" Label

Is he a sea monster? Sorta. But he’s technically an "amphibious kairyu."

The distinction matters because a true sea monster, like the Kraken or a Mosasaur, can't survive on land. Godzilla’s unique biology allows him to transition between high-pressure aquatic environments and the low-pressure atmosphere of a city without his internal organs exploding. This is a feat of biological engineering that would baffle any real-world evolutionary biologist.

👉 See also: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

His heart has to be massive. His blood pressure must be high enough to keep his brain oxygenated while standing upright, yet flexible enough to not cause a stroke when he’s 5,000 feet down.

Mapping Godzilla’s Most Famous Ocean Encounters

- The Odo Island Incident (1954): The first time we see him, he’s just a silhouette behind a mountain, but the destruction of fishing boats previously set the stage.

- The Battle of the Antarctic (2004): In Godzilla: Final Wars, he’s frozen in the ice, showing his incredible resistance to extreme temperatures.

- The Tasman Sea Brawl (2021): The definitive proof that Kong is out of his depth in the water. Godzilla nearly drowns the ape before the humans intervene with depth charges.

The Future of the King Under the Waves

As our real-world oceans change, so does the depiction of Godzilla. With rising sea levels and ocean acidification becoming major global talking points, future films will likely lean even harder into Godzilla as a "Nature’s Reset Button."

We’re seeing more focus on his role in the ecosystem. He’s no longer just a "destroyer of cities." He’s the apex predator that keeps other "Titans" in check so they don't destroy the planet's biosphere. He’s a gardener, and the ocean is his backyard.

If you’re looking to track Godzilla in the ocean—at least in the movies—keep an eye on the "Monarch" maps. The producers usually base his travel routes on real tectonic plate boundaries and geothermal hotspots. It’s a nice touch of realism in a franchise about a radioactive dinosaur.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Creators

If you are writing about or researching Godzilla's aquatic nature, keep these specific points in mind to stay accurate to the lore:

- Check the Era: A Toho Godzilla (1954-2004) has different aquatic abilities than the Legendary Monsterverse Godzilla. Toho’s version is more magical/mystical; Legendary’s is more biological/evolutionary.

- Watch the Tail: In animation and modern CGI, the tail is the primary source of movement. If you see him "walking" on the bottom of the ocean, it's usually a sign of a shallower continental shelf, not the open deep.

- Radiation is Key: Godzilla doesn't eat fish. He "eats" radiation. His movements in the ocean are always dictated by where the highest concentrations of nuclear energy are located.

- The Gills Debate: Only specific versions of Godzilla have visible gills. If you're discussing the 1990s "Heisei" era, he’s strictly a lung-breather who happens to be a world-class swimmer.

The ocean remains the only place where Godzilla is truly at peace. It’s the only place big enough to hold him. While we see him as a threat to our concrete jungles, in the vast, dark stretches of the Pacific, he’s just an animal returning home.

To dive deeper into the science of kaiju biology, look into the works of paleontologists like Darren Naish, who has occasionally blogged about the "speculative biology" of Godzilla. Understanding the real-world physics of deep-sea gigantism can give you a whole new appreciation for why Godzilla in the ocean is the most terrifying—and fascinating—version of the character.