You’re standing in a stadium. Maybe it’s Wembley or Twickenham. The crowd swells, the brass section kicks in, and suddenly thousands of people are beltng out a tune that everyone knows, yet surprisingly few people actually know all of. We’re talking about the lyrics for england national anthem, "God Save the King."

It’s a weird one. Honestly, it’s less of a song and more of a cultural reflex. But here’s the kicker: it’s not technically the "English" anthem in a legal sense, and it’s certainly not just about a catchy melody. Since the passing of Queen Elizabeth II in 2022, the song underwent its first major linguistic shift in over seventy years. Just changing "Queen" to "King" and "her" to "him" sounds simple on paper, but for a nation that had only known one version for decades, it was a massive psychological pivot.

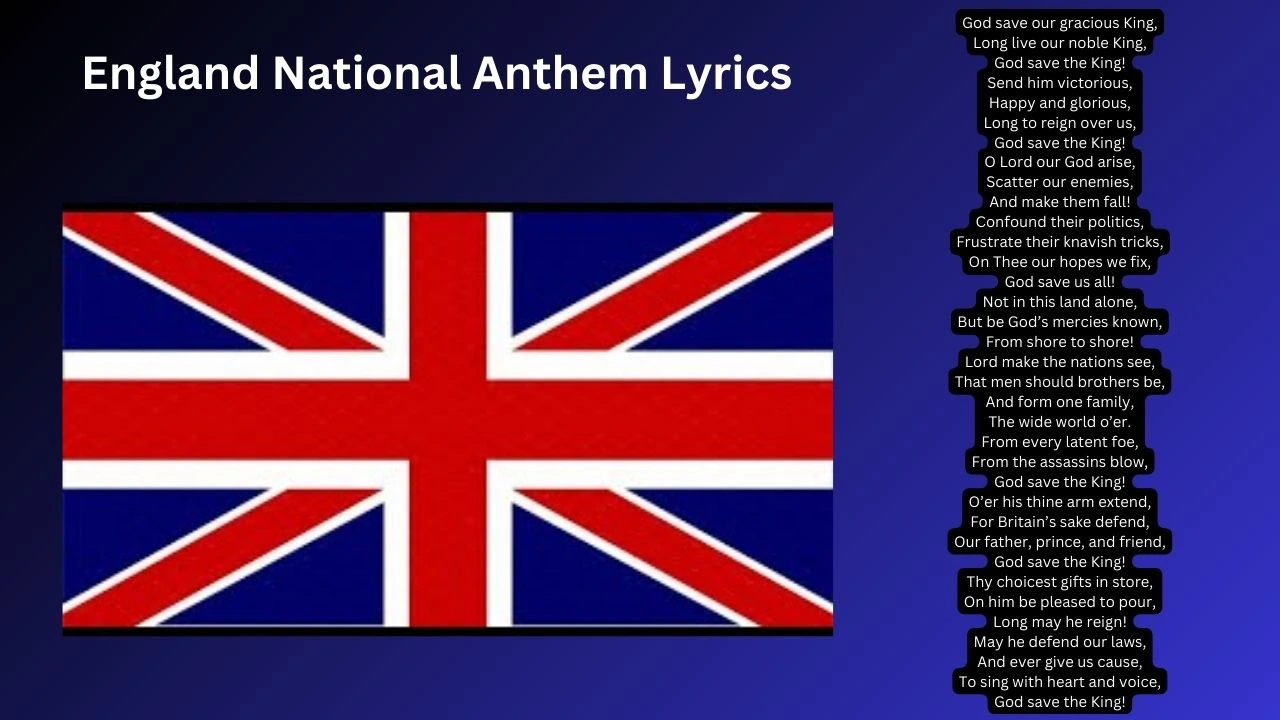

The Words Everyone Mumbles After the First Verse

Most people can nail the first verse. It’s burned into the collective consciousness.

God save our gracious King!

Long live our noble King!

God save the King!

Send him victorious,

Happy and glorious,

Long to reign over us:

God save the King.

But what happens after that? If you’ve ever watched a major sporting event, you’ve probably noticed the music usually fades out after those first seven lines. There’s a reason for that. The second and third verses are... well, they’re a bit intense. They reflect a time when Britain was constantly at war and the monarchy was a literal shield against foreign "knavery."

The second verse goes like this:

O Lord, our God, arise, / Scatter his enemies, / And make them fall. / Confound their politics, / Frustrate their knavish tricks, / On Thee our hopes we fix, / God save us all.

"Knavish tricks" is a fantastic phrase, but it’s definitely a product of the 1740s. It’s aggressive. It’s defensive. It’s very much about survival in a hostile 18th-century Europe. When you hear the lyrics for england national anthem today, these lines are almost always skipped to keep the vibe more celebratory and less "we hope our enemies fail miserably."

👉 See also: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

Who Actually Wrote This Thing?

Nobody knows. Seriously.

There is no single credited composer or author. It’s one of the great mysteries of music history. Some people point to Thomas Arne, who famously arranged the version performed at Drury Lane in 1745. Others swear it has roots in plainchant or even an old Carol. The tune has been attributed to everyone from John Bull to Henry Carey, but the truth is it likely evolved through the "folk process"—people just kept singing it and changing it until it stuck.

By the time the Jacobite rising of 1745 rolled around, the song became a massive hit in London theaters. It was a political statement. To sing it was to say, "I support the Hanoverian King George II, not the Stuart 'Pretender' coming down from Scotland."

Is it England's Anthem or Britain's?

This is where things get genuinely confusing for people outside the UK (and many inside it). England does not have its own official, legal national anthem. "God Save the King" is the national anthem of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Because England is the largest part of the UK, it just sort of "borrowed" the British anthem for its own sporting events.

Compare this to the other home nations. Scotland has "Flower of Scotland." Wales has "Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau" (Land of My Fathers), which is, frankly, a musical masterpiece that usually outshines "God Save the King" in terms of raw emotion at rugby matches. England, meanwhile, sticks with the UK-wide anthem, though there have been decades of debate about whether they should switch to something uniquely English.

✨ Don't miss: Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus Explained (Simply)

The Contenders for a New English Anthem

If England ever decided to get its own song, there are three main candidates that usually top the polls:

- Jerusalem: Based on William Blake's poem. It’s arguably more popular than the actual anthem. It’s sung at the Commonwealth Games and is deeply tied to the English identity.

- Land of Hope and Glory: It’s grand, it’s loud, and it’s the staple of the Last Night of the Proms.

- There'll Always Be an England: Very nostalgic, very World War II era.

For now, though, the lyrics for england national anthem remain tied to the monarch. It’s a hymn of loyalty.

The Forgotten (and Controversial) Verses

There is a "rebellious Scots" verse that often gets brought up in heated Twitter debates. It was a temporary addition during the 1745 rebellion:

Lord, grant that Marshal Wade, / May by thy mighty aid, / Victory bring; / May he sedition hush, / and like a torrent rush, / Rebellious Scots to crush, / God save the King.

To be clear: this verse is not part of the official anthem. It hasn't been sung in any formal capacity for over 250 years. It was a product of a very specific, very violent civil conflict. Most historians view it as a historical footnote rather than a part of the song's actual DNA. Bringing it up today is usually just a way to stir the pot before a Calcutta Cup rugby match.

There’s also a third verse that is much more peaceful, focusing on the "choicest gifts in store" being poured upon the King. It’s rarely used because, let’s be honest, people just want to get to the kickoff or the trophy presentation.

Why the Lyrics Still Matter in 2026

Symbols matter. When the lyrics changed from "Queen" to "King," it wasn't just a grammatical fix. It marked the end of the second Elizabethan age. For the first time in most people's lives, they had to consciously think about the words they were singing.

🔗 Read more: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

The anthem serves as a bridge. It connects the modern, digital England of 2026 with a Georgian era of powdered wigs and wooden ships. Whether you’re a staunch monarchist or someone who just likes football, the song is a ritual. It’s about the "we," not just the "him" in the lyrics.

When England plays in the World Cup, those lyrics for england national anthem represent a moment of rare national unity. It’s the one time you’ll see 80,000 people agreeing on the same set of words—even if they’re mostly just humming through the second half of the verse.

Practical Steps for the Curious

If you’re heading to a match or a formal event, don't be the person caught opening and closing your mouth like a goldfish when the music starts.

- Learn the pronouns. It’s "King," "him," and "his." If you say "her," you’ll stand out for the wrong reasons.

- Keep it to the first verse. Unless specifically told otherwise, 99% of performances stop after "God save the King."

- Stand up. It’s standard etiquette. Even if you aren't a fan of the monarchy, standing is generally seen as a mark of respect for the event and the country.

- Listen to the tempo. Different conductors play it at different speeds. Don't be the person who finishes three seconds before the band.

The anthem isn't going anywhere. It’s survived revolutions, world wars, and the rise of the internet. It’s a stubborn piece of music that refuses to be updated, largely because its power lies in its age. It’s a piece of living history that you get to shout at the top of your lungs.

Next time you hear those opening notes, remember you're singing a song that was essentially the world's first viral hit, long before the internet made that a thing. It’s a weird, slightly aggressive, deeply traditional, and utterly English paradox.

To truly understand the song, one should look at the 1953 coronation recordings versus the 2023 coronation. The lyrics are essentially the same, but the weight of the words shifts with the person on the throne. It’s a reminder that while the King might change, the song—and the complex national identity it represents—remains the constant.