Glenn Gould was the kind of guy who would wear a heavy overcoat, gloves, and a wool hat in the middle of a sweltering July. He was obsessed with germs, hated being touched, and famously abandoned the concert stage at the age of 31 because he thought live performance was a "blood sport" that degraded the music. You’d think a man like that would hide in a basement. Instead, he became one of the most televised and filmed classical musicians in history.

Honestly, it's a bit of a paradox. Gould didn't just appear in films; he treated the camera like a long-distance confessional. If you look into Glenn Gould movies and tv shows, you aren't just looking at concert footage. You’re looking at a man who believed the electronic medium was the only way to achieve "the state of wonder and serenity." He didn't want to play to you; he wanted to play for a lens that would then broadcast his genius to you in the safety of your living room, where he couldn't see you and you couldn't cough on him.

The Big One: Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould

If you only watch one thing about him, make it the 1993 film Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould. It isn't a normal biopic. There’s no "and then he went to school" narrative. It’s a series of vignettes—thirty-two of them, mirroring the structure of Bach’s Goldberg Variations.

Directed by François Girard, the film stars Colm Feore, who basically becomes Gould. He nails the posture: that low-slung, hunched-over-the-keys look that made Gould's spine look like a question mark. One scene is just Gould in a truck stop diner, listening to the overlapping conversations of the patrons as if it were a complex fugue. It’s brilliant because it shows how Gould didn't just hear music—he heard the world as a contrapuntal structure.

The film also tackles the weird stuff. Like the "CD318" segment, which focuses on his beloved, battered Steinway piano. Or the pills. Gould had a pharmacy’s worth of Valium and Librax in his bathroom. The movie doesn't judge; it just observes. It’s as cold and precise as one of his recordings, yet oddly moving.

✨ Don't miss: Austin & Ally Maddie Ziegler Episode: What Really Happened in Homework & Hidden Talents

The CBC Years and the "Art of the Fugue"

Before the big documentaries, there were the raw, black-and-white television broadcasts. Between 1954 and 1977, Gould was a fixture on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). These weren't just "sit and play" shows. He was a producer, a writer, and a bit of a comedian.

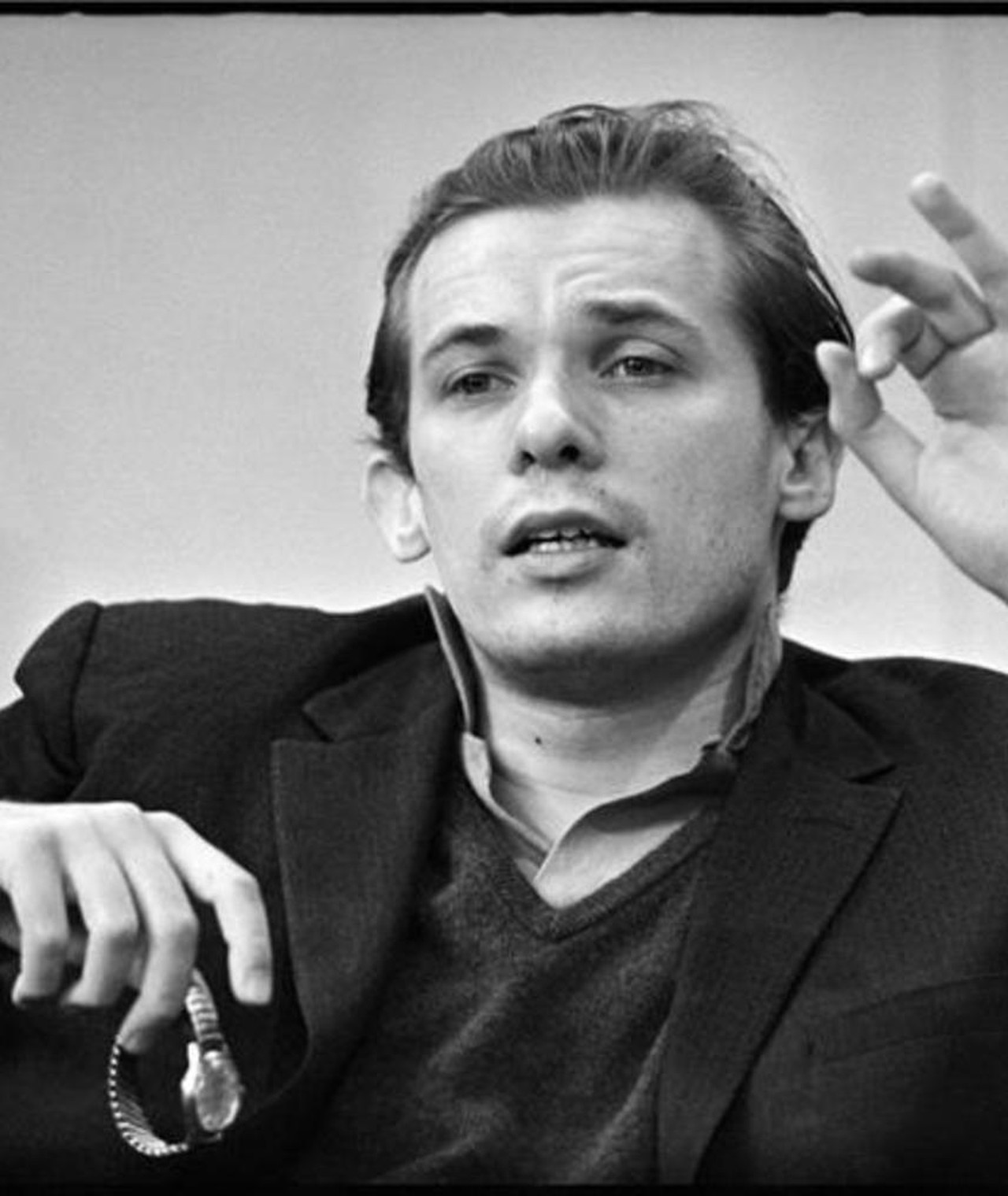

He created programs like The Anatomy of the Fugue (1963) and The Well-Tempered Listener. In these, you see Gould the educator. He’d sit at the piano, talk directly to the camera with an intense, caffeinated energy, and explain Schoenberg or Bach like he was let in on a secret the rest of us were too slow to grasp.

You should check out Glenn Gould on Television: The Complete CBC Broadcasts. It’s a massive 10-DVD set that came out a while back. It’s roughly 19 hours of him doing everything from playing with Yehudi Menuhin to conducting interviews with himself in various accents. He loved masks. He loved characters. Television allowed him to be everyone and no one at the same time.

Bruno Monsaingeon and the Final Masterpieces

If François Girard gave us the poetic Gould, the French filmmaker Bruno Monsaingeon gave us the technical one. Monsaingeon was a friend and collaborator who filmed Gould during his final years.

🔗 Read more: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

The most famous of these is the 1981 film of the Goldberg Variations. It’s a stark contrast to his 1955 debut recording. Here, he’s older, slower, more meditative. The camera stays tight on his face and hands. You can hear him humming—that famous, scratchy, off-key vocalizing that drove sound engineers crazy but became his trademark.

Monsaingeon also directed Glenn Gould: Hereafter (2006). This documentary is a great entry point because it uses Gould's own words, narrated (in some versions) by actor Mathieu Amalric, to weave together his philosophy. It feels less like a tribute and more like a posthumous conversation.

The Documentary Deep Dives

For those who want the "real" story—or as close as you can get to a guy who lived on the phone and rarely let people in his apartment—there are two major documentaries to hunt down:

- Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould (2009): This one caused a bit of a stir because it broke the "lonely monk" myth. It delved into his long-term affair with Cornelia Foss, the wife of composer Lukas Foss. It shows a more human, albeit still very complicated, side of Gould.

- Glenn Gould: Off the Record / On the Record (1959): These are two short films produced by the National Film Board of Canada. They are "fly on the wall" style. You see him at his cottage, walking by the lake, and then in the studio in New York. It’s probably the most "natural" footage of him that exists.

Why He Still Trends on Your Screen

Why do we keep making Glenn Gould movies and tv shows? Why isn't he just another dead pianist?

💡 You might also like: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

Basically, Gould was the first "digital" artist in an analog world. He predicted the internet. He predicted that the "listener" would eventually be able to edit and mix their own music at home. His life was a performance of solitude that resonates in our current era of remote work and screen-mediated lives.

He didn't just use TV to show off; he used it to build a world where he could be safe. When you watch The Idea of North, his "contrapuntal radio documentary" that was later adapted for TV, you see his obsession with the Canadian Arctic. It was a metaphor for his own life: isolated, cold, but incredibly pure.

How to Watch Gould Today

If you’re looking to dive into the filmography, don't just start with a random YouTube clip.

- Start with Thirty Two Short Films: It sets the mood and gives you the "vibe" of his personality without getting bogged down in dates.

- Watch the 1981 Goldberg Variations film: It is the essential visual record of his playing style. Watch his fingers—they barely lift off the keys.

- Find the CBC archives: Many of these are now available through the Glenn Gould Estate or the NFB. Look for Glenn Gould's Toronto, where he walks you through the city he rarely left, despite his fame.

Gould once said that "the camera is a friend." For a man who didn't have many close ones in the physical world, the lens was where he finally felt understood. He wasn't just a musician; he was a media pioneer who used the screen to ensure his ideas would outlive his fragile, overmedicated body. And it worked. Every time someone clicks play on a Gould documentary, the recluse from Toronto is exactly where he wanted to be: in your head, but at a very safe distance.

To truly understand Gould's visual legacy, your next step should be seeking out the National Film Board of Canada's digital archives; they host several of his early short films for free, providing the most unvarnished look at the man before the "eccentric genius" persona became a global brand.