Ever wonder why a pile of iron rusts in the rain without you doing a single thing, yet a diamond doesn't just spontaneously turn into a lump of graphite? Or why ice melts the second it hits room temperature? It all comes down to a concept that sounds like a sci-fi power source but is actually the backbone of every chemical reaction in the universe: Gibbs Free Energy.

Honestly, the name is a bit of a mouthful. But back in the 1870s, an American scientist named Josiah Willard Gibbs—a guy Albert Einstein called "the greatest mind in American history"—cracked the code on how to predict the future. Specifically, he figured out how to tell if a chemical reaction would happen on its own or if you’d have to pump energy into it like a car that ran out of gas.

The "Free" Energy That Isn't Actually Free

When we talk about Gibbs Free Energy (usually just called $G$), we aren't talking about something you get for zero dollars. The "free" part refers to the energy that is available to do work. Think of it like your bank account balance after you've set aside money for rent and utilities. It’s the "disposable income" of a chemical system.

In a lab or a human cell, we rarely care about the total energy. We care about the change in energy, written as $\Delta G$. If $\Delta G$ is negative, the reaction is spontaneous. It wants to happen. It’s rolling downhill. If $\Delta G$ is positive, the reaction is a non-starter unless you provide an outside "push."

The Tug-of-War: Enthalpy vs. Entropy

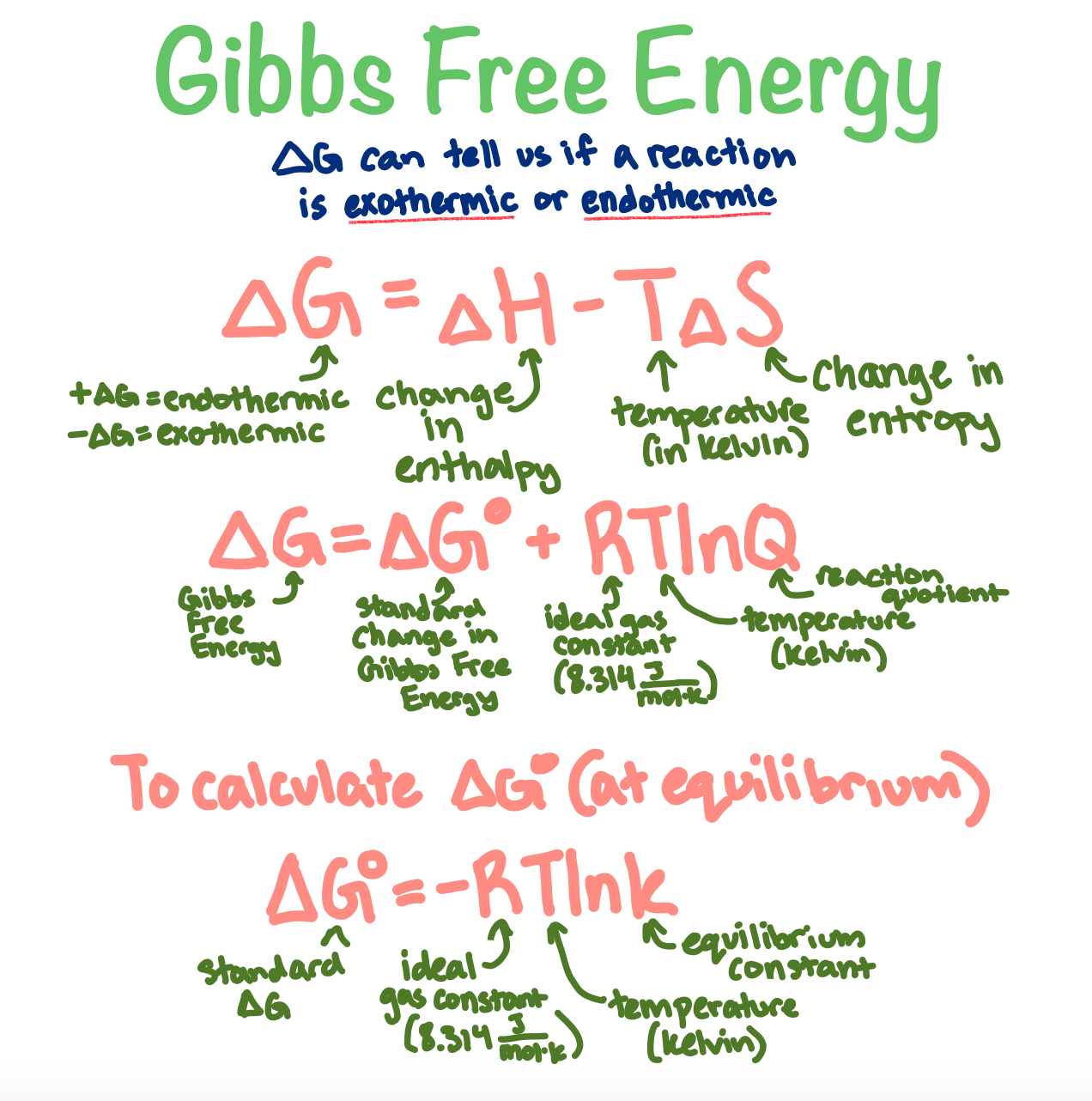

The formula for Gibbs Free Energy is a classic:

$$\Delta G = \Delta H - T \Delta S$$

It looks simple, but it represents a massive cosmic struggle between two opposing forces:

- Enthalpy ($\Delta H$): This is basically heat content. Most things in nature want to be at a lower energy state (releasing heat, or exothermic).

- Entropy ($\Delta S$): This is the "disorder" or "randomness" of a system. The universe loves a mess.

- Temperature ($T$): This is the referee. It determines which of the other two forces wins the fight.

Take melting ice. Breaking the bonds in ice requires heat (positive $\Delta H$), which usually makes a reaction "unfavorable." But liquid water is way more disordered than a solid crystal (positive $\Delta S$). At low temperatures, the heat requirement wins, and the ice stays frozen. But as you crank up the temperature, the $T \Delta S$ term gets bigger and bigger until it outweighs the heat requirement. Suddenly, $\Delta G$ flips to negative, and—poof—the ice melts.

Why Spontaneous Doesn't Mean "Right Now"

Here is where most people get tripped up. In plain English, "spontaneous" means something happens suddenly or impulsively. In thermodynamics, it just means "thermodynamically allowed."

A reaction can be spontaneous and still take a billion years to happen.

Take the diamond on your finger. Graphite is actually a more stable form of carbon at standard pressure. This means the conversion from diamond to graphite has a negative $\Delta G$. It is a spontaneous process. But you don't see jewelry turning into pencil lead because the activation energy—the "hump" the reaction has to climb over—is so high that it practically never happens.

Gibbs tells you if you can get to the destination. It doesn’t tell you if the road is blocked by a massive mountain.

📖 Related: Fire Stick Free TV: What Most People Get Wrong About Cutting the Cord

Real-World Stakes: From Your Phone to Your DNA

You’ve probably got a lithium-ion battery within arm's reach. The reason your phone works is because we’ve engineered a system where a chemical reaction has a massive negative $\Delta G$. When you use your phone, you’re letting that reaction happen, "harvesting" the free energy as electricity. When you plug it in, you’re using external energy to force a positive $\Delta G$ reaction to run backward, "recharging" the potential.

In biology, this is even more critical. Your body is a master of "reaction coupling." Many of the things your cells need to do (like building DNA) have a positive $\Delta G$. They shouldn't happen. To fix this, your body hitches these "uphill" reactions to the breakdown of ATP—a molecule with a very large negative $\Delta G$. It’s like using a heavy weight on a pulley to lift a smaller bucket.

Common Misconceptions to Watch Out For

- "Spontaneous reactions always release heat." Nope. Melting ice is spontaneous at room temperature, but it absorbs heat (endothermic). It’s the entropy increase that drives it.

- "If $\Delta G$ is zero, nothing is happening." Not quite. When $\Delta G = 0$, the system is at equilibrium. The forward and backward reactions are happening at the exact same rate. It’s a dynamic stalemate.

- "Gibbs and Helmholtz are the same." They’re cousins. Gibbs free energy is used for systems at constant pressure (like a beaker on a desk). Helmholtz free energy ($A$) is for systems at constant volume.

How to Use This Knowledge

If you’re a student or a curious engineer, don't just memorize the formula. Look at the units. $\Delta H$ is usually in kilojoules (kJ), but $\Delta S$ is often in joules (J). You have to convert them before you plug them in, or your math will be off by a factor of a thousand.

Also, remember that $T$ must be in Kelvin. You can’t have a negative temperature in Kelvin, which is why the $T \Delta S$ term behaves so predictably as things get hotter.

Practical Next Steps:

🔗 Read more: Why Cursive Font Copy Paste Is Still Everywhere and How It Actually Works

- Check the sign: Before doing any deep math, look at the signs of $\Delta H$ and $\Delta S$. If $\Delta H$ is negative and $\Delta S$ is positive, the reaction is always spontaneous. No math needed.

- Calculate the crossover: If you want to find the exact temperature where a reaction becomes spontaneous, set $\Delta G$ to zero and solve for $T = \Delta H / \Delta S$.

- Connect to $K$: Use the relationship $\Delta G^\circ = -RT \ln K$ to see how much product you’ll actually get at equilibrium. A very negative $\Delta G$ means you'll have almost all product and no reactant left.

Understanding Gibbs Free Energy is essentially learning the "permission settings" of the physical world. It tells us what is possible, even if it doesn't always tell us when.