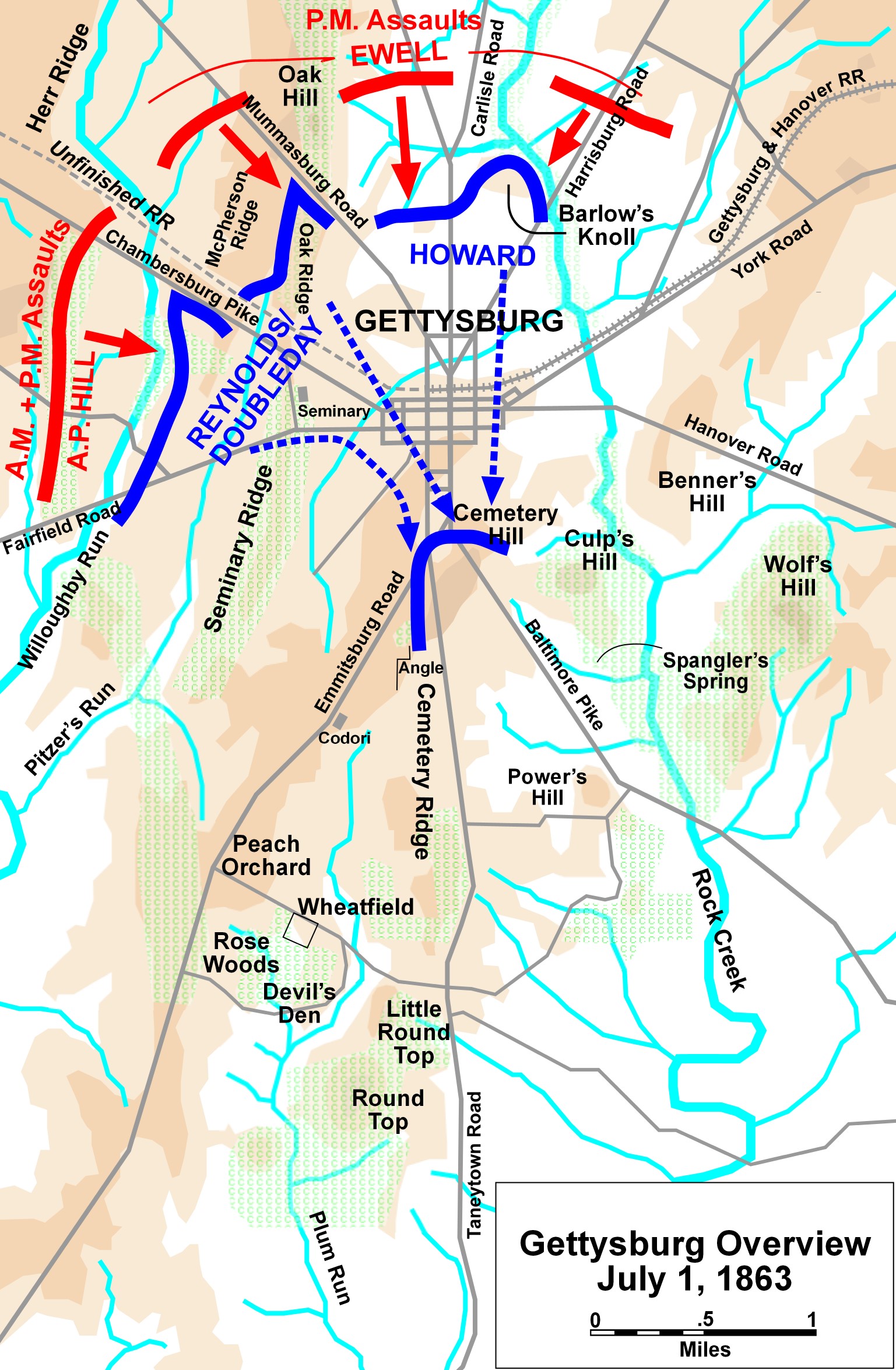

It started with shoes. Or maybe it didn't. Most historians, like the late Shelby Foote, will tell you the whole "Confederates looking for footwear" story is a bit of a myth, or at least a massive oversimplification. What actually happened on July 1, 1863, was a chaotic, unplanned collision. If you look at a Gettysburg battle map day 1, you don’t see a neat line of soldiers. You see a frantic scramble for the high ground. It was a Wednesday. By the time the sun went down, the fields north and west of a tiny crossroads town were soaked in the blood of over 15,000 men.

The geography of that first day is everything. Honestly, if you don't understand the ridges, the map is just a bunch of squiggles. You've got McPherson’s Ridge, Seminary Ridge, and the ultimate prize: Cemetery Hill.

The Morning Scuffle at McPherson’s Ridge

John Buford was a guy who understood terrain. He was a Union cavalry commander who arrived in Gettysburg on June 30 and realized immediately that if he didn't hold the hills, the Union army was toast. He looked at the Gettysburg battle map day 1 and saw a funnel. He dismounted his troopers. They were outnumbered. Henry Heth’s Confederate division was marching East on the Chambersburg Pike, expecting maybe a few local militia. Instead, they ran into professional cavalry with Spencer repeating rifles.

Speed mattered. Buford’s men were basically buying time with their lives. They were waiting for John Reynolds and the First Corps to show up. Reynolds was a local legend from Pennsylvania, the kind of guy people thought might lead the whole army one day. He arrived, spurred his horse forward to urge the Iron Brigade into the woods, and was shot dead instantly. A sharpshooter’s bullet changed the course of American history in a heartbeat.

The fighting at Herbst’s Woods was brutal. The 24th Michigan and the 26th North Carolina absolutely decimated each other. We’re talking about some of the highest casualty rates of the entire war in just a few hours. When you trace the lines on a map from this specific hour, you see this weird, jagged back-and-forth near the railroad cut. That railroad cut became a death trap. Union soldiers used it for cover, but it was too deep. They couldn't see out. Confederates swarmed the edges and fired down. It was a slaughterhouse.

The Collapse of the Eleventh Corps

By midday, things were looking okay for the North, but then the map shifted. Richard Ewell’s Confederate Second Corps started arriving from the North. This is where the Gettysburg battle map day 1 gets really ugly for the Union. They had to stretch their line into a "half-circle" to protect the town. It was too thin.

💡 You might also like: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

The Union Eleventh Corps, many of whom were German immigrants, got stuck in the flat ground north of town. They’re often blamed for the retreat, which is kinda unfair. They were flanked. Robert Rodes’s Confederates poured down from Oak Hill—the highest point on that part of the field—and just smashed the Union right wing.

If you’re standing at the Eternal Light Peace Memorial today, you’re looking at where Rodes’s artillery opened up. It’s a commanding view. From up there, the Union soldiers below looked like sitting ducks. Francis Barlow, a Union general, made a tactical error by moving his men to a small rise now called Barlow’s Knoll. He got isolated. He got shot. His men broke and ran.

Chaos in the Streets

Imagine a town of 2,400 people suddenly filled with thousands of panicked, retreating soldiers. It wasn't a clean withdrawal. It was a rout.

Confederates were chasing Federals through alleys, backyards, and even through the halls of the Lutheran Seminary. The Gettysburg battle map day 1 shows a massive bottleneck in the center of Gettysburg. Many Union soldiers were captured because they simply got lost in the side streets.

But here is the turning point. The "What If" of the century.

📖 Related: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

General Richard Ewell had orders from Robert E. Lee to take the high ground south of town—Cemetery Hill—"if practicable." Ewell looked at his tired men. He looked at the Union artillery already humming on the hill. He decided it wasn't practicable. He stopped.

Winfield Scott Hancock, sent by George Meade to take command after Reynolds died, stayed on that hill. He pointed his finger at the ground and said they would stay there. That decision, visible on any tactical Gettysburg battle map day 1, basically won the battle for the North two days before it actually ended. By securing that "fishhook" shape on the hills, the Union gave themselves the inner lines.

Why the First Day Often Gets Ignored

People love to talk about Pickett’s Charge or the 20th Maine at Little Round Top. I get it. Those are cinematic. But Day 1 was a full-scale battle on its own. It was the 23rd largest battle of the entire Civil War just by the numbers of that single Wednesday.

The Confederates won the day. No doubt about it. They drove the Union off the field and occupied the town. But they failed to finish the job. They let the Union keep the "fishhook."

When you study the Gettysburg battle map day 1, you see a series of Confederate missed opportunities. Heth shouldn't have engaged so early. Ewell should have pushed the hill. Longstreet was still miles away. It was a day of "almosts."

👉 See also: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

Realities of the Map Today

- The Railroad Cut: You can still see where the 6th Wisconsin captured the 2nd Mississippi. It’s a literal hole in the ground that changed the momentum for an hour.

- The Seminary Cupola: General John Buford watched the battle develop from the top of the Lutheran Seminary. You can visit this today. Seeing the sightlines explains why he chose to fight where he did.

- Oak Hill: This is where the Confederate tide really started to roll. The height advantage here is staggering.

Actionable Insights for Your Visit

If you're heading to the battlefield to trace the Gettysburg battle map day 1 yourself, don't just stay in the car. Most people do the auto-tour and miss the nuances of the terrain.

First, go to the McPherson Barn. Stand there and look West. You’ll see the slight dips in the ground where the Confederates disappeared and reappeared as they marched toward the Union lines. It’s eerie.

Second, check out the Eleventh Corps markers on the north side of town. It’s mostly flat. You’ll instantly see why they were in trouble. There’s no cover. It’s just open fields where they stood and took it until they couldn't take it anymore.

Finally, walk up Cemetery Hill at dusk. Look back toward the town. You’ll see exactly what Richard Ewell saw. You’ll see how formidable that hill looked and why he hesitated.

To really grasp the scale, download a high-resolution topographic map from the Library of Congress. The modern park maps are great for tourists, but the historical maps show the woodlots and fences that actually dictated how men moved and died.

The first day wasn't just a prelude. It was the moment the South’s best chance at a decisive victory on Northern soil began to slip away, one ridge at a time. Trace those lines, walk the ridges, and you'll see that the map isn't just paper—it's the reason the United States looks the way it does today.