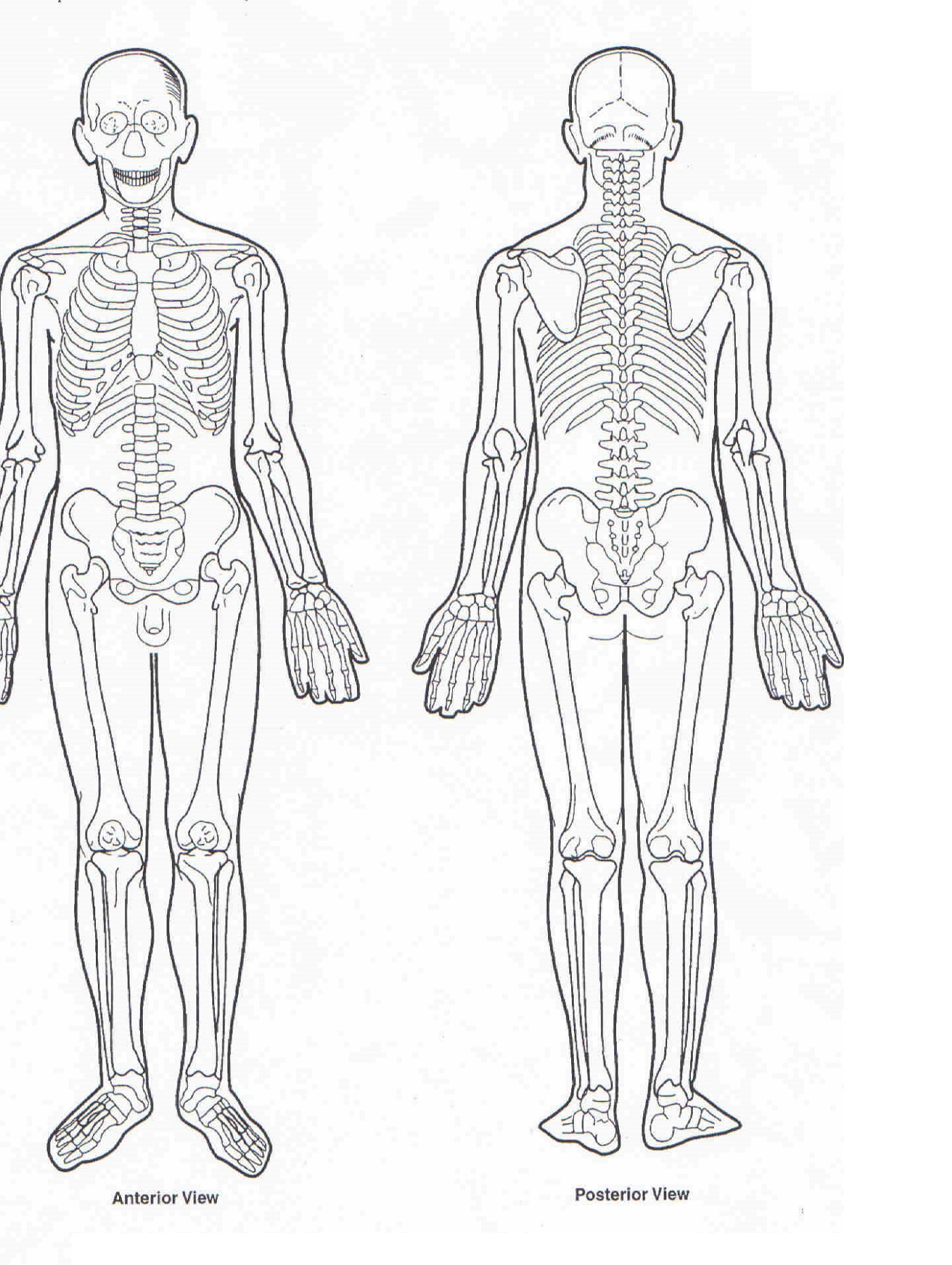

You spend most of your life looking at the front of yourself in the mirror, but the real heavy lifting happens where you can't see. Your back is a mechanical masterpiece. It’s a dense, layering mess of cables, pulleys, and bone that keeps you upright while protecting your most vital communication line—the spinal cord. When you look at a diagram of the back of the human body, it’s easy to get overwhelmed by the Latin names and the overlapping fibers.

But honestly? It’s simpler than it looks if you think of it as a suspension bridge.

The spine is the main pylon. The muscles are the cables. If one cable gets too tight or too loose, the whole bridge starts to creak. Most of us don't think about our posterior anatomy until we throw out our back picking up a grocery bag or feel that nagging burn between our shoulder blades after a long day at a desk. Understanding what’s actually happening under your skin can be the difference between chronic pain and moving well into your eighties.

The Architecture of the Spine: More Than Just Bone

The centerpiece of any diagram of the back of the human body is the vertebral column. It’s not just one long bone. It’s 33 individual vertebrae stacked like a precision-engineered tower. You’ve got seven cervical vertebrae in your neck, twelve thoracic vertebrae in your mid-back (where your ribs attach), and five lumbar vertebrae in your lower back. Below that, the sacrum and coccyx—your tailbone—anchor everything into the pelvis.

The lumbar region is usually where the drama happens. This area carries the bulk of your body weight. Because these five vertebrae are so mobile compared to the rigid thoracic spine above them, they take a beating. Between each bone sits an intervertebral disc. Think of these as jelly donuts. They absorb shock. When people talk about a "slipped" or herniated disc, they basically mean the jelly is squishing out and poking a nerve. It’s incredibly painful because that space is already crowded with the cauda equina, the bundle of nerves that looks like a horse's tail.

📖 Related: Why PMS Food Cravings Are So Intense and What You Can Actually Do About Them

The Muscles You Can See (And the Ones You Can't)

If you peel back the skin on a back diagram, the first thing you see is the Trapezius. It’s that massive diamond-shaped muscle that runs from the base of your skull down to the middle of your back and out to your shoulders. It’s the "shrug" muscle. Underneath that, you have the Latissimus Dorsi, or "lats." These are the wide, wing-like muscles that give swimmers that V-taper. They are your primary pulling muscles.

But the real heroes are the deep layers.

- The Erector Spinae group. This is a bundle of three muscles (iliocostalis, longissimus, and spinalis) that run vertically along your spine. Their entire job is to keep you from folding over like a wet noodle.

- The Multifidus. These are tiny, triangular muscle fascicles that stitch the vertebrae together. Recent research, including studies published in The Spine Journal, suggests that atrophy in the multifidus is one of the biggest predictors of chronic lower back pain. If these tiny guys stop firing, the big muscles try to do their job, they get tired, and then everything starts to hurt.

It’s a chain reaction. You can’t just look at the lower back in isolation. The Thoracolumbar Fascia is this thick, diamond-shaped patch of connective tissue in your lower back that acts as a junction point. It connects your glutes, your lats, and your core. If your glutes are weak—which is common if you sit all day—this fascia gets tugged on, and your lower back feels the strain.

Why Your Mid-Back Feels Like a Moving Target

The thoracic spine is built for rotation. Or at least, it’s supposed to be. In a standard diagram of the back of the human body, you’ll notice the ribs create a sort of cage around this area. This protects your heart and lungs, but it also makes the area naturally stiffer than your neck or lower back.

👉 See also: 100 percent power of will: Why Most People Fail to Find It

Modern life is a disaster for this section of the anatomy.

We spend hours hunched over phones or steering wheels. This leads to "Upper Crossed Syndrome," a term coined by Dr. Vladimir Janda. Your chest muscles get tight, pulling your shoulders forward, and the muscles in your back—specifically the Rhomboids and the lower Trapezius—get stretched out and weak. They’re like overstretched rubber bands. They lose their ability to pull your shoulder blades back together. This is why you get those "knots" (trigger points) near your shoulder blades. Your muscles are literally gasping for blood flow because they’re being held in a stretched position for eight hours a day.

The Nerve Highway

We can't talk about the back without mentioning the Sciatic Nerve. It’s the longest and widest nerve in the human body. It starts in your lower back, runs through your buttock, and goes all the way down to your toes. In many diagrams, you'll see it peeking out from under the Piriformis muscle in the hip.

When the lower back is misaligned or a disc is bulging, it can pinch the roots of this nerve. This results in sciatica—that lightning-bolt pain that shoots down your leg. It’s a perfect example of how a problem in the back can manifest somewhere completely different.

✨ Don't miss: Children’s Hospital London Ontario: What Every Parent Actually Needs to Know

Moving From Anatomy to Action

Understanding the diagram of the back of the human body isn't just an academic exercise. It's about knowing how to maintain the machine. You can't just "fix" a back; you have to manage it.

- Hydrate the discs. Intervertebral discs are mostly water. Throughout the day, gravity squeezes fluid out of them (you’re actually slightly shorter at night than you are in the morning). Movement and hydration help keep them plump and functional.

- Decompress the spine. Simply hanging from a pull-up bar for 30 seconds can create space between the vertebrae. It lets the discs breathe.

- Wake up the glutes. Since the glutes and the back are linked via the thoracolumbar fascia, a "lazy butt" often leads to a "painful back." Squats and lunges are back exercises, even if you don't feel them there.

- Address the "Text Neck." For every inch your head moves forward from a neutral position, it adds about 10 pounds of pressure to the cervical spine. Tuck your chin. Pull your shoulder blades down into your "back pockets."

Stop thinking of your back as a solid wall. It’s a dynamic, living system of tension and compression. When you look at a diagram now, don't just see labels. See the connections. The lats pulling on the hips, the traps supporting the skull, and the spine holding the whole story together. Take care of the cables, and the bridge will stay standing.

To put this into practice, start by incorporating "cat-cow" stretches and "bird-dogs" into your morning routine. These movements specifically target the multifidus and erector spinae muscles without putting excessive load on the spinal discs. If you work at a desk, set a timer for every 50 minutes to perform three deep "scapular retractions"—squeezing your shoulder blades together as if trying to hold a pencil between them. This counters the forward pull of gravity and keeps the thoracic muscles engaged. Consistent, small movements are far more effective for long-term back health than occasional, intense workouts.