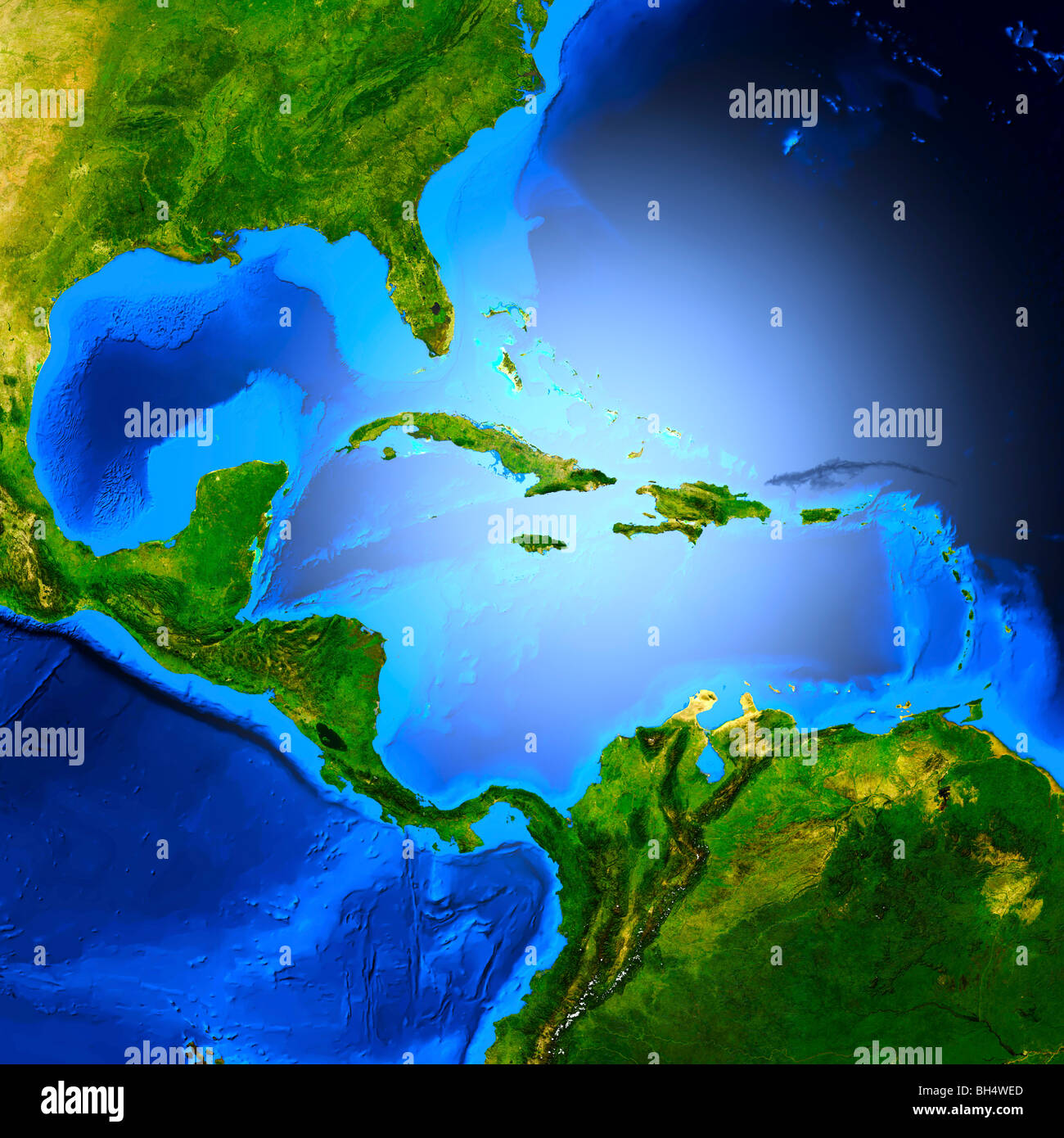

Most people look at a Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea map and see a giant, blue blob. It’s easy to do. You see Florida poking out like a thumb, the curve of Mexico, and a scattering of islands that look like breadcrumbs leading toward South America. But if you're a navigator, a marine biologist, or even just a hardcore cruiser, that map is a lie. Well, not a lie, exactly, but it's a massive oversimplification of one of the most complex aquatic systems on the planet.

The Gulf isn't just "the ocean near Texas." The Caribbean isn't just a vacation backdrop. They are two distinct, moody, and interconnected basins that dictate the weather for half the globe.

Honestly, when you start tracing the lines, you realize how much of our history is buried in these depths. We're talking about the Chicxulub crater—the literal "dinosaur killer"—sitting under the Yucatan Peninsula. We’re talking about the Loop Current, a massive "heat engine" that turns tropical storms into monsters. If you want to understand why a hurricane in the Caribbean suddenly explodes in intensity before hitting New Orleans, you have to stop looking at the map as a static image and start seeing it as a living circulatory system.

The Invisible Border: Where the Gulf Ends and the Caribbean Begins

People get this wrong all the time. They think it’s all just "the tropics." But geologically, they’re worlds apart.

The boundary is basically the Yucatan Channel. It's a 125-mile-wide squeeze play between Mexico and Cuba. Water from the Caribbean gets shoved through this narrow gap into the Gulf of Mexico. This is where things get interesting. Because the Caribbean is generally deeper—reaching over 25,000 feet in the Cayman Trench—it holds a massive amount of thermal energy. When that warm water hits the shallower, bowl-shaped Gulf, it creates a pressure cooker effect.

Look at a Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea map and trace the 200-meter isobath. That's the continental shelf. In the Gulf, that shelf is massive, especially off the coast of Florida and Louisiana. In the Caribbean, the drop-offs are vertical and terrifying. You can be in knee-deep turquoise water in the Bahamas and, a few miles away, you're hovering over a five-mile-deep abyss. That depth difference changes everything from the color of the water to the types of sharks that might be eyeing your surfboard.

The Loop Current: The Gulf’s Secret Engine

If you’ve ever wondered why the Gulf of Mexico is so much warmer than the Atlantic at the same latitude, look at the "Loop."

✨ Don't miss: Hotel Gigi San Diego: Why This New Gaslamp Spot Is Actually Different

Water enters from the Caribbean, loops around the Gulf like a runaway garden hose, and then shoots out through the Florida Straits to become the Gulf Stream. Dr. Nan Walker at LSU has done some incredible work documenting how this current sheds "eddies." These are giant spinning circles of warm water that break off and drift. If a hurricane passes over one of these warm eddies, it’s like throwing gasoline on a fire. The storm doesn't just grow; it undergoes "rapid intensification."

That's why the map is so vital for the National Hurricane Center. They aren't just looking at where the land is. They are looking at the heat map of the water underneath.

Why the Caribbean Isn't Just "South" of the Gulf

It’s easy to think of the Caribbean as just the basement of the Gulf, but it’s actually a massive tectonic playground. The Caribbean Plate is constantly grinding against the North American and South American plates. This is why the islands look the way they do on your Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea map.

You have the Greater Antilles—Cuba, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Puerto Rico. These are basically submerged mountain ranges. Then you have the Lesser Antilles, that beautiful arc of islands on the eastern edge. Those are volcanic. They are the result of one plate sliding under another and melting.

- The Cayman Trench: The deepest part of the Caribbean, reaching roughly 25,217 feet.

- The Mesoamerican Barrier Reef: Stretching from the Yucatan down to Honduras, it's the second-largest reef system in the world.

- The Mississippi Delta: The "drainage pipe" of North America, dumping 15 million tons of sediment into the Gulf every month.

These features aren't just trivia. They define the economy. The Gulf is a working sea. It’s dominated by oil rigs, shrimp boats, and massive cargo ships heading into the Port of South Louisiana. The Caribbean, meanwhile, is the world’s most tourism-dependent region. One relies on what’s under the seabed; the other relies on the clarity of the water above it.

The "Dead Zone" Nobody Likes to Put on the Map

We need to talk about the smudge on the map. Every summer, a "Dead Zone" forms in the northern Gulf of Mexico. It’s an area of hypoxia—low oxygen—where fish and shrimp basically suffocate.

🔗 Read more: Wingate by Wyndham Columbia: What Most People Get Wrong

Why? Because the Mississippi River collects all the fertilizer runoff from the Midwest and dumps it right into the Gulf. This triggers massive algae blooms. When the algae dies and sinks, it uses up all the oxygen. In some years, this zone is the size of New Jersey.

When you look at a Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea map, you don't see the Dead Zone. It’s invisible. But for the thousands of people whose livelihoods depend on those waters, it’s the most important feature on the chart. It's a stark reminder that what happens in a cornfield in Iowa directly affects the blue water of the Gulf.

Mapping the Deep: The Hidden Shipwrecks

There are over 4,000 shipwrecks in the Gulf of Mexico alone. Some are Spanish galleons laden with silver; others are German U-boats from World War II. Yes, Nazis were active in the Gulf. They were hunting oil tankers right off the coast of Louisiana.

In the Caribbean, the map is a graveyard of colonial ambition. The "Silver Bank" off the coast of the Dominican Republic is named that for a reason. In 1641, the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción hit a reef and dumped a fortune in Spanish silver into the sea. People are still finding coins there.

Modern mapping technology, like LIDAR and side-scan sonar, is finally letting us see the "basement" of these seas. We're finding coral forests in the midnight zone and brine pools—lakes at the bottom of the ocean that are so salty they are toxic to most life.

Navigating the Politics of the Map

The lines on a Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea map aren't just for show. They represent Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs). Every country with a coastline gets 200 nautical miles of "ownership" over the resources in that water.

💡 You might also like: Finding Your Way: The Sky Harbor Airport Map Terminal 3 Breakdown

This gets messy. Fast.

In the Caribbean, you have dozens of small island nations with overlapping claims. In the Gulf, it’s mostly a three-way split between the U.S., Mexico, and Cuba. There’s a spot in the middle of the Gulf known as the "Western Gap" or the "Doughnut Hole." For years, it was international water, a weird legal vacuum. Eventually, the U.S. and Mexico had to sit down and draw a line through it because there was a high chance of oil being down there. Nobody wants to leave billions of dollars in "no man's land."

Practical Steps for Travelers and Navigators

If you’re planning to use a Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea map for anything more than a wall decoration, you need to be smart about it. The water here is fickle.

- Check the Bathymetry: If you’re boating, don't just look at the blue. Look at the depths. The West Florida Shelf stays shallow for a long time, which means waves get choppy and "square" very quickly in a storm.

- Monitor the Current: If you're sailing from Cozumel to Florida, you are fighting the Yucatan Current. It can run at 4 knots. If your boat only does 6 knots, you're barely moving. Use real-time satellite data to find the "path of least resistance."

- Understand the Seasons: The "map" changes. In winter, "Northers" (cold fronts from Canada) can turn the Gulf into a washing machine. In summer, the Caribbean is a mirror—until a tropical wave rolls off the coast of Africa.

- Support Conservation: These waters are under pressure. Whether it’s sargassum seaweed blooms choking Caribbean beaches or coral bleaching in the Flower Garden Banks (the northernmost coral reefs in the U.S.), the map is showing signs of stress. Choose operators who respect the Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) marked on your charts.

The best way to respect these waters is to understand them. A map is just a starting point. The real story is in the temperature of the water, the depth of the trenches, and the way the currents link a tiny island in the Antilles to a pier in Galveston. It’s all connected.

Next time you see a Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea map, don't just look for your destination. Look at the channels. Look at the shelf. Look at the way the land bends around the water. You’ll see a much more interesting world once you realize the blue parts are the most active places on the planet.