Drawing hardware isn't like drawing a face. You can mess up a jawline by a millimeter and it’s just "character," but if you mess up the receiver on a drawing of machine gun, the whole thing looks like a melting plastic toy. It’s frustrating. I’ve seen incredibly talented character artists crumble when they have to illustrate a belt-fed weapon because they treat it like a static object instead of a machine with moving parts.

Perspective kills. Most people try to draw these things from a flat side-profile because it’s easier, but that’s how you end up with a drawing that has zero soul. If you want it to look real, you have to understand how the gas system interacts with the barrel. You have to see the weight.

The Anatomy Most People Ignore

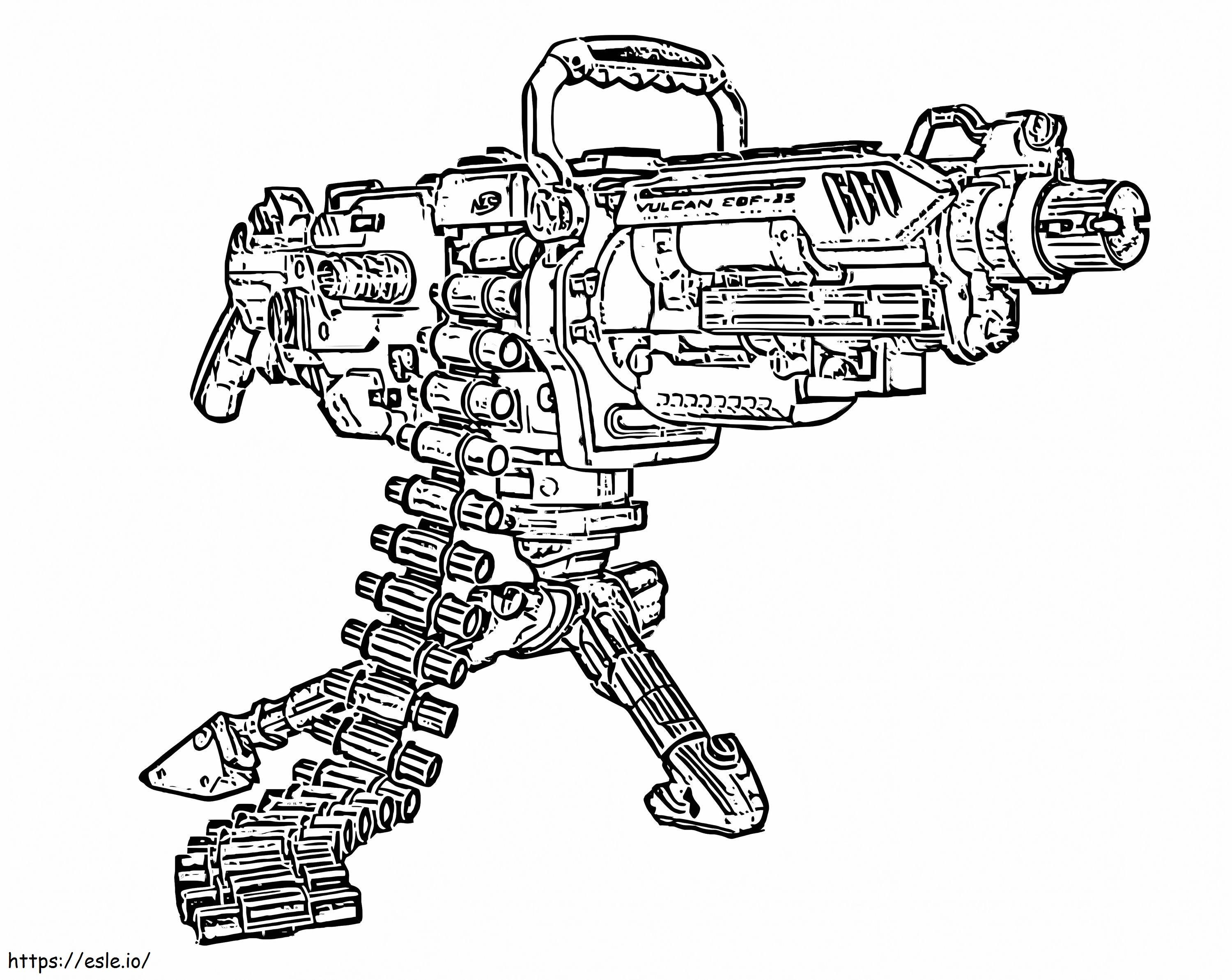

You can't just draw a long tube and a box and call it an M2 Browning. Details matter. Specifically, the relationship between the receiver and the feeding mechanism. If you’re looking at a drawing of machine gun, the first thing your eye should hit isn't the barrel—it's the breach. That’s where the "violence" of the machine happens.

Realism comes from the small stuff. Think about the cooling fins on an air-cooled barrel. Or the way a bipod actually hinges. If you draw a bipod as two sticks glued to the bottom, it looks fake. In reality, there’s a pivot point. There’s a locking lug. Reference the Lewis Gun from World War I; that massive cooling shroud around the barrel is iconic, but if you don't get the proportions of the pan magazine right, it looks like a dinner plate stuck on a pipe.

Managing Scale and Proportions

It’s big. Machine guns are usually much larger than people realize. If you’re drawing a character holding an M249 SAW, the weight should be visible in their posture. The strap should dig into the shoulder. Honestly, the most common mistake is making the weapon too small, like a toy rifle. A real light machine gun is a hunk of steel and polymer that weighs 15 to 25 pounds. It’s awkward. It’s heavy.

✨ Don't miss: Boynton Beach Boat Parade: What You Actually Need to Know Before You Go

Your lines should reflect that. Use heavier line weights for the underside of the receiver to ground the object.

Perspectives That Actually Work

Forget the side view. Seriously. If you want to grab attention on social media or in a portfolio, you need a three-quarter view. This allows you to show the depth of the feed tray. You get to see the bullets sitting in the belt.

Drawing ammunition is its own nightmare. Don’t draw every single bullet with the same level of detail. It’ll look cluttered and messy. Instead, focus on the first three bullets entering the feed tray. Make those crisp. As the belt drapes down toward the ammunition box, let the detail soften. This creates a natural focal point. It guides the viewer’s eye exactly where you want it to go: the heart of the weapon.

The Texture of Steel vs. Polymer

Weapons aren't just one material. A modern drawing of machine gun usually involves a mix of parkerized steel, anodized aluminum, and high-impact polymers.

🔗 Read more: Bootcut Pants for Men: Why the 70s Silhouette is Making a Massive Comeback

- Steel has sharp, specular highlights. It reflects light in thin, bright streaks along the edges of the stamping.

- Polymer is matte. It soaks up light. If you’re drawing an HK MG5, the stock and grip should have a softer, grainier texture compared to the cold, hard lines of the barrel.

- Heat Discoloration is a pro tip. If the gun has been fired, the barrel near the gas block will have a slight iridescent sheen or a darker, burnt matte finish. Adding that tiny detail tells a story. It says this gun isn't just a prop; it’s being used.

Common Mistakes in Action Poses

The muzzle flash is usually drawn wrong. It’s not a fireball like in a cartoon. It’s often a star-shaped burst or a horizontal spray depending on the muzzle brake. If you’re doing a drawing of machine gun in the middle of a "mad minute" of firing, show the spent casings flying out.

But wait. Where do they eject?

Most artists just have them flying out the side randomly. Look at the specific model. An M60 ejects to the side, but some weapons eject downward. Also, remember the links. Belt-fed guns don't just spit out brass; they spit out the metal links that hold the belt together. If you include the disintegrating links in your drawing, you immediately separate yourself from the amateurs. It shows you actually looked at a technical manual or watched slow-motion footage on YouTube.

Light and Shadow on Mechanical Forms

Don’t use soft airbrushing for everything. Machined parts have hard edges. Use a hard round brush for your initial shading. You want those transitions between light and dark to be snappy. When light hits a cylindrical barrel, it creates a very specific highlight—a long, straight line that follows the length of the tube. If that line wobbles, the barrel looks bent. Use a ruler tool or a steady-stroke stabilizer.

💡 You might also like: Bondage and Being Tied Up: A Realistic Look at Safety, Psychology, and Why People Do It

Shadows are your friend. The area under the top cover or behind the charging handle should be deep, dark black. This creates contrast. It makes the metallic parts "pop."

The "Used" Look

A brand new gun is boring to draw. It’s just a black silhouette. The real magic happens in the weathering.

Think about where a soldier’s hands touch the weapon. The edges of the magazine well, the charging handle, and the safety selector will have the finish worn off. This reveals the bright silver of the aluminum or steel underneath. Scratches should be purposeful. Don't just scramble lines everywhere. Put a long scratch along the side of the receiver where it might have rubbed against a belt buckle or a vehicle door. This kind of environmental storytelling makes the drawing feel lived-in.

Practical Steps for Your Next Piece

To truly master a drawing of machine gun, stop drawing from memory. Even the pros don't do that.

- Find a technical breakdown. Search for "field strip" photos of the specific model. This shows you how the parts fit together without the housing. Understanding the "skeleton" makes drawing the "skin" much easier.

- Block out the major volumes. Use simple 3D primitives. A box for the receiver, a cylinder for the barrel, and a triangle for the grip. Get the perspective right in this stage. If the boxes are wrong, the detail won't save it.

- Focus on the "Joinery." Pay attention to where the barrel meets the receiver. This is the most common point of failure in a drawing. It needs to look reinforced and sturdy.

- Vary your line weights. Use thick lines for the outer silhouette and paper-thin lines for things like screw heads, pins, and serial numbers.

- Check your belt tension. If the gun is belt-fed, the belt should have a natural "S" curve as it hangs. It shouldn't be a straight line. Gravity acts on those heavy rounds.

Avoid the temptation to over-complicate the background. If the weapon is the star of the show, keep the environment muted. A simple grit texture or some blurred debris is enough. The goal is to make the viewer feel the coldness of the metal and the mechanical complexity of the design. Stick to the references, mind your perspective, and don't forget the ejection port.