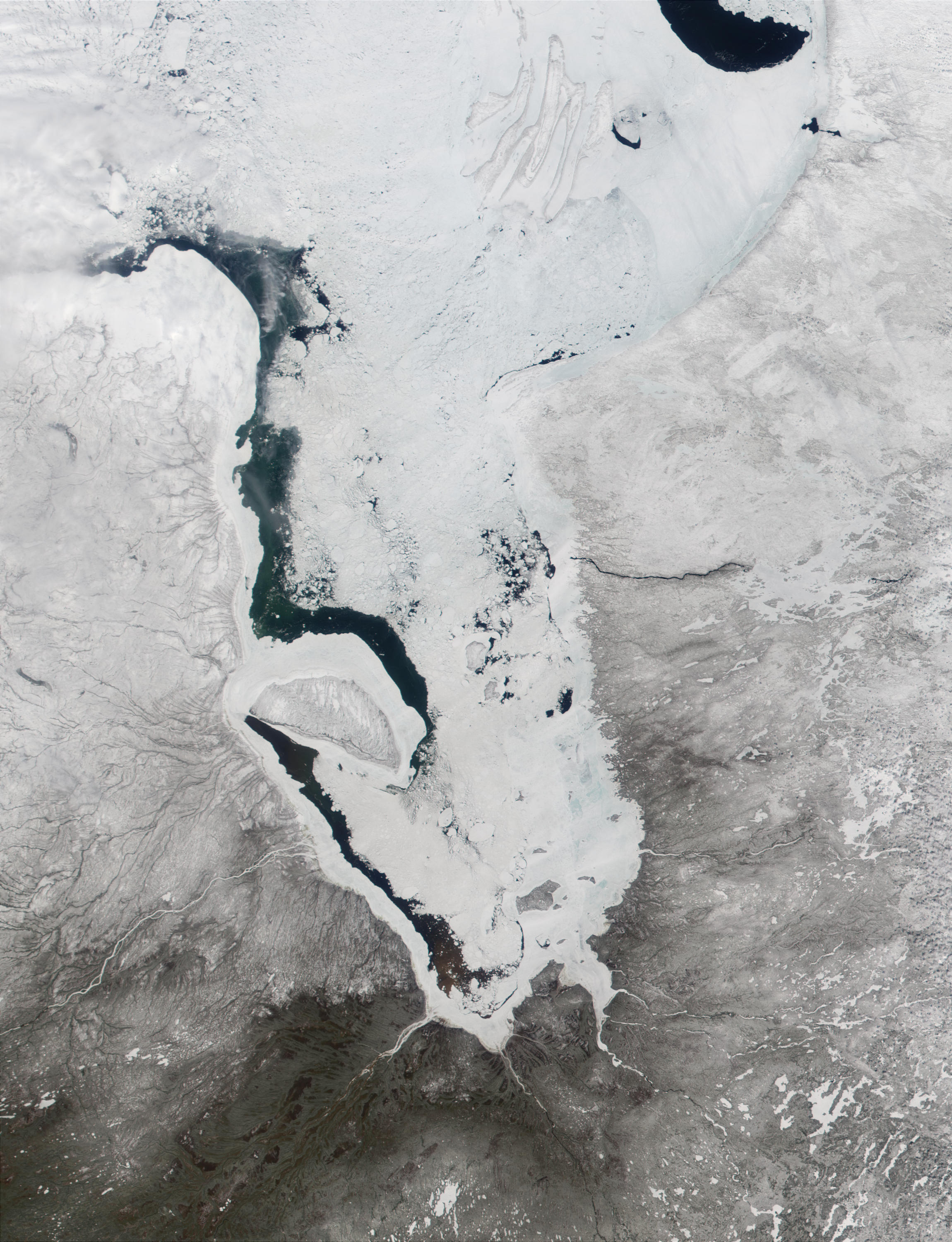

If you zoom out on a digital map of James Bay Canada, the first thing you notice is that massive, distinct "U" shape carved into the bottom of Hudson Bay. It looks like a giant thumbprint pressed into the Canadian Shield. Most people just see a big blue void on their screens and scroll past. That's a mistake.

This place is huge.

Seriously, James Bay is roughly the size of West Virginia, yet it feels like another planet entirely. It’s where the boreal forest finally gives up and lets the tundra take over. Looking at a map, you see names like Chisasibi, Moosonee, and Waskaganish scattered along the coast like crumbs. These aren't just dots on a grid; they are some of the oldest continuously inhabited spots in North America. The Cree (Iyiyuu) have been navigating these waters since long before European cartographers tried to claim the coastline. Honestly, if you’re looking at a standard map, you’re only seeing half the story. The geography here is fluid, literally.

The Weird Geometry of the Map of James Bay Canada

Most maps lie to you about the North. They make it look static. But the map of James Bay Canada is actually changing because of something called post-glacial rebound. The land is rising. Since the massive weight of the glaciers from the last Ice Age vanished, the earth is slowly springing back up like a squished sponge. This means the shoreline today isn't exactly where it was 200 years ago.

Navigation is a nightmare here.

The bay is incredibly shallow. While Hudson Bay reaches depths of over 700 feet, James Bay averages only about 100 feet. In some spots, you can be miles from shore and still be in water shallow enough to stand in—though I wouldn't recommend it given the temperature. This makes for a jagged, treacherous coastline on any nautical chart. You’ve got thousands of tiny islands, many of them unnamed, that appear and disappear with the tides.

Akimiski Island is the biggest hunk of land you’ll see on the map. It’s part of Nunavut. Wait, what? Yeah, even though it sits right off the coast of Ontario, all the islands in the bay belong to the territory of Nunavut. It’s a jurisdictional quirk that makes managing the land a bit of a bureaucratic headache. If you're standing on the shore in Quebec or Ontario, you're in one province, but the second your boot touches an island a few hundred yards out, you've technically entered the Arctic territory.

The Great River Arteries

You can't talk about the geography without mentioning the rivers. They are the lifeblood of the region. Look at the eastern shore on the Quebec side (Eeyou Istchee). You'll see the La Grande River. This isn't just a river anymore; it’s a massive industrial machine. The James Bay Project transformed this area into one of the largest hydroelectric systems in the world.

📖 Related: Bryce Canyon National Park: What People Actually Get Wrong About the Hoodoos

The map shows a string of massive reservoirs—LG-2 (Robert-Bourassa), LG-3, LG-4—that look like blue ink stains spreading across the wilderness. These reservoirs flooded thousands of square kilometers of traditional Cree hunting grounds. It changed the map forever. On the west side, the Ontario side, things are flatter. The Moose River flows into the bay at Moosonee, the "Gateway to the Arctic." There are no roads to Moosonee. You take the Polar Bear Express train or you fly.

Why the Borders Look So Strange

Look closely at the border between Ontario and Quebec as it hits the bay. It’s a straight line that suddenly hits the water and vanishes. Historically, the entire James Bay drainage basin was part of Rupert's Land, controlled by the Hudson's Bay Company. When Canada bought that land in 1870, the borders were drawn by guys in offices in Ottawa and London who had never stepped foot in a muskeg swamp.

The Cree communities didn't care about these lines.

They moved with the seasons.

- Attawapiskat: Remote, famous for the Victor Diamond Mine, and sitting on the edge of the James Bay Lowlands.

- Fort Albany: One of the oldest former fur-trading posts, split between an island and the mainland.

- Wemindji: A coastal community in Quebec that literally means "vermilion paint mountain."

These communities are the anchors of the map. Without them, the map is just a cold, empty space. But for the people living there, it’s a dense network of snowmobile trails, bush pilot routes, and ancient water paths.

The Ghost of Henry Hudson

James Bay is named after Thomas James, a Welsh captain who explored it in 1631. But the guy who really put it on the map (unwillingly) was Henry Hudson. In 1611, after a brutal winter trapped in the ice, Hudson’s crew mutinied. They set him, his son, and a few loyalists adrift in a small boat right in the middle of this bay.

They were never seen again.

👉 See also: Getting to Burning Man: What You Actually Need to Know About the Journey

When you look at the map of James Bay Canada, you’re looking at a giant crime scene. There is a haunting quality to the vastness. It’s a place that swallows people who don't respect the scale of the landscape.

The Lowlands: A Carbon Bomb

South and west of the bay lies the James Bay Lowlands. This is the largest wetland in North America. On a topographic map, it looks boring—mostly flat and green. In reality, it’s one of the most important ecosystems on Earth. It’s a massive peatland. Peat is basically half-decomposed plant matter that stores carbon.

If this area thaws or is drained for mining, it releases that carbon.

The "Ring of Fire" is a term you’ll see if you look at mineral maps of this region. It’s a massive deposit of chromite, nickel, and copper located in the lowlands. It’s currently at the center of a massive tug-of-war between mining companies, the provincial government, and First Nations. The map of the future might include a controversial north-south road cutting through this swamp to get those minerals out.

Climate Change is Redrawing the Lines

The Arctic is warming faster than almost anywhere else. In James Bay, this isn't a theoretical problem; it’s a map problem. The sea ice is forming later and melting earlier. For the polar bears that live in the southernmost part of their range here, the map of the ice is their map of survival.

When the ice is gone, they can't hunt seals.

The winter roads are also disappearing. These are roads literally built out of packed snow and ice that connect remote communities to the south for a few weeks every year. They are vital for trucking in fuel and building supplies. As the climate warms, the window of time these roads are open is shrinking. On a paper map, a road looks like a road. In James Bay, a road is a temporary miracle of sub-zero temperatures.

✨ Don't miss: Tiempo en East Hampton NY: What the Forecast Won't Tell You About Your Trip

How to Actually "Read" This Map

If you want to understand this region, don't just look at the physical features. Look at the infrastructure—or the lack of it.

- The Billy Diamond Highway: Formerly the James Bay Road. It’s a 620-km stretch of paved road from Matagami to Radisson. There are no gas stations for nearly 400 kilometers. If you break down here, you better have a satellite phone.

- The Rail Lines: Look for the thin black line heading north from Cochrane to Moosonee. It’s the lifeline for the western bay.

- The Flight Paths: Most travel here happens in small planes. Twin Otters and Dash-8s are the buses of the North.

Actionable Steps for the Curious Explorer or Researcher

If you're actually planning to use a map of James Bay Canada for travel or research, stop using Google Maps. It’s not detailed enough for the bush.

Get the right tools. Use the National Topographic System (NTS) of Canada. These 1:50,000 scale maps show every creek, contour line, and swamp boundary. They are essential for anyone going off-grid.

Check the tides. If you're near the coast, remember that the tide in James Bay can move the shoreline by hundreds of meters because the land is so flat. What looks like a campsite on a map might be a salt marsh by 2:00 AM.

Consult local knowledge. The most accurate "map" of James Bay exists in the heads of the Cree hunters and trappers. If you are traveling to a community like Eastmain or Kashechewan, check in with the local band office. They can tell you which trails are washed out and where the ice is thin.

Monitor the ice. For real-time data on the bay's conditions, use the Canadian Ice Service. This will give you a better idea of what the "map" actually looks like today, rather than a stylized satellite image from three years ago.

James Bay is a place of extremes. It is a massive carbon sink, a hydroelectric powerhouse, and a cultural heartland. Whether you're looking at it for its mineral potential or its ecological beauty, remember that the map is just a flat representation of a very deep, very complex reality. Don't underestimate the scale. Don't ignore the history. And definitely don't forget that up here, the land is always rising.