Let’s be real. If you’ve spent more than five minutes trying to learn German, you have probably stared at a German adjective endings table until your eyes crossed. It’s that terrifying grid of -en, -er, -es, and -em that seems to change every time you turn your back. Honestly, it feels like a conspiracy. You think you’ve mastered the word for "the blue car" (das blaue Auto), but then someone says "with a blue car" (mit einem blauen Auto), and suddenly the rules have shifted under your feet. It’s exhausting.

German grammar isn't trying to hurt you, even if it feels that way. The language is just hyper-specific. While English speakers just throw the word "green" in front of anything and call it a day, German demands to know the gender, the case, and whether or not there’s an article hanging out nearby. It’s about "case signaling." If the article (der, die, das) isn’t doing the heavy lifting of telling the listener the case, the adjective has to step up and do the job.

The Three Worlds of Declension

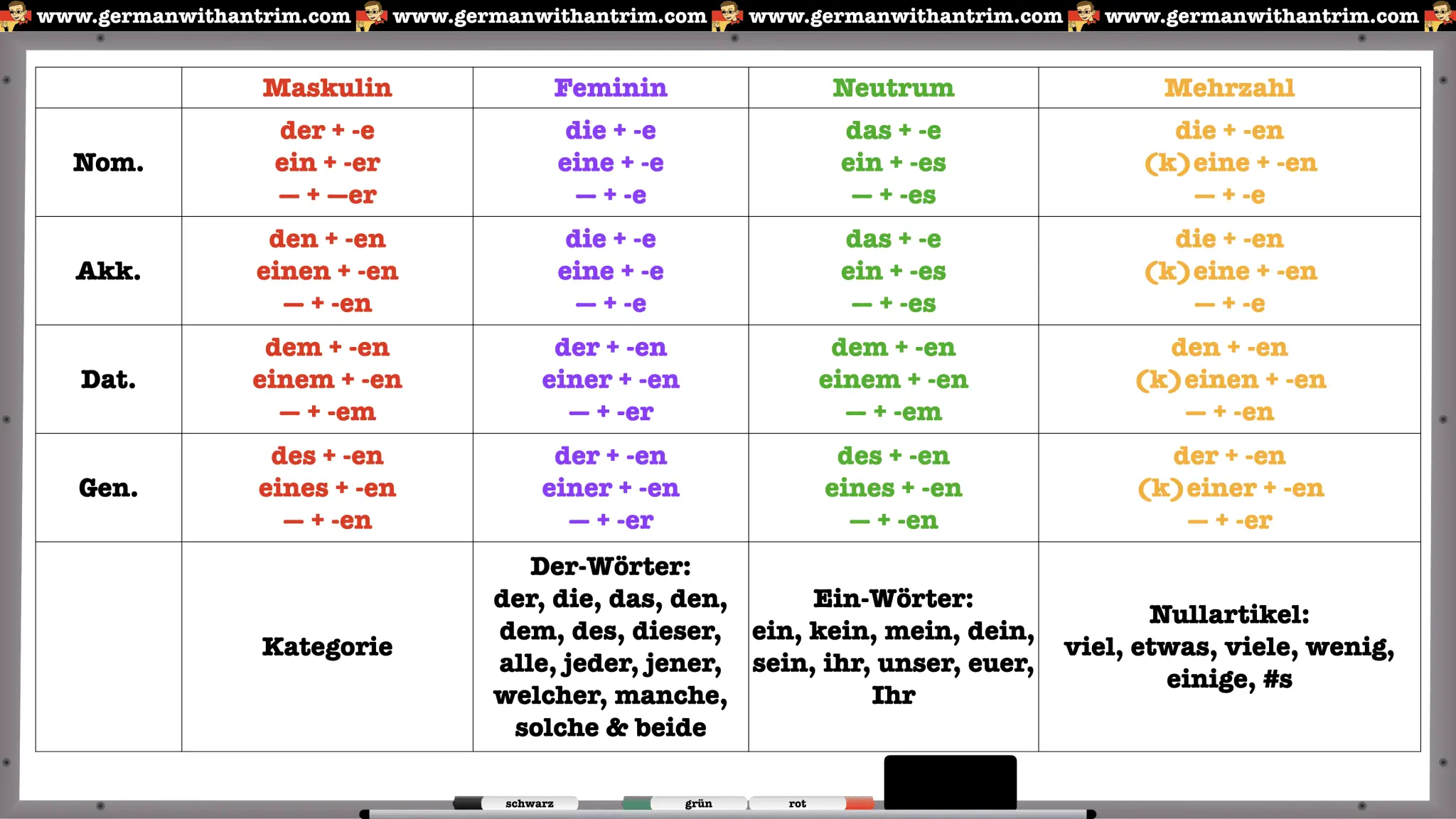

Most people get tripped up because they think there is just one "table." There isn’t. There are actually three distinct scenarios, and knowing which one you’re in is half the battle. We call these weak, strong, and mixed declensions. It sounds like something out of a physics textbook, but it’s basically just a way to describe how much work the adjective has to do.

Weak declension happens when you have a "definite" article. Think der, die, das, den, dem, des. These words are strong. They clearly state, "Hey, I'm a masculine nominative noun!" or "I'm a dative plural!" Because the article is doing all the signaling, the adjective gets lazy. In a German adjective endings table for weak declension, you’ll notice a lot of simple -e or -en endings. It’s the easiest path. For example, der kleine Hund (the small dog). The der tells us everything, so klein just takes a simple -e.

Then things get spicy with strong declension. This is the "no article" zone. If you’re saying "cold water" (kaltes Wasser) without a das or an ein, the adjective kalt has to take on the ending that the article would have had. Since Wasser is neuter and we are in the nominative/accusative case, the adjective grabs that -s from das. It’s a survival tactic. The adjective is the only thing left to tell the listener what’s going on grammatically.

The "Ein" Problem: Mixed Declension

Mixed declension is where the most mistakes happen. This is the realm of ein, eine, mein, dein, kein. These words are a bit "weak" in some cases and "strong" in others. Specifically, in the masculine nominative and the neuter nominative/accusative, ein doesn't have a distinctive ending. It’s just ein. It doesn't tell you if the noun is masculine or neuter.

Because ein is failing at its job, the adjective has to jump in.

Ein guter Mann (A good man).

Ein schönes Buch (A beautiful book).

The -er and the -es are there because ein left a gap. However, as soon as you hit the dative case—like mit einem guten Mann—the einem is already doing the work with that -em ending. So, the adjective reverts to being "lazy" and just takes an -en.

💡 You might also like: How many oz in a 1.75 liter? The Math Behind Your Liquor Cabinet

Why the Dative Case is Your Secret Shortcut

If you’re panicking about a test or a conversation, here is a tip that saves lives: in the dative and genitive cases, across almost all tables, the adjective ending is almost always -en.

Seriously.

Whether it's mit dem großen Tisch, von einer alten Frau, or wegen des schlechten Wetters, that -en is incredibly consistent. If you find yourself in a complex sentence and you know you’re using a preposition like mit, nach, von, seit, aus, zu, or bei, just slap an -en on that adjective. You’ll be right 90% of the time. It’s the closest thing to a "cheat code" in German grammar.

Plurals are Actually Easier Than You Think

Plurals scare people because they think it's more of the same. But look at a German adjective endings table for plurals. If there is any article in front of a plural noun—whether it's die (definite) or meine, keine, seine—the adjective ending is always -en.

Die grünen Bäume.

Meine teuren Schuhe.

Keine kalten Getränke.

The only time it changes is when there is absolutely no article at all, like "green trees are pretty" (Grüne Bäume sind schön). In that specific "no article plural" case, the adjective takes the -e. That's it. Two options. That is much more manageable than the singular masculine mess.

Common Misconceptions and Where Students Fail

The biggest mistake? Overthinking the "Gender."

Many learners spend way too much time memorizing whether a "table" is masculine or feminine. You should be memorizing the trigger. The trigger is the word before the adjective.

Is it a "Der-word"? (Weak)

Is it an "Ein-word"? (Mixed)

Is it nothing? (Strong)

🔗 Read more: Why joggers for women cargo are basically the only pants you need right now

If you identify the category of the word preceding the adjective first, the choice of ending becomes a logical deduction rather than a wild guess. Expert linguists often suggest that instead of memorizing three separate tables, you should learn the "Rese-Nese" pattern for strong endings and the "En-En" rule for plural datives.

Another stumbling block is the "Accusative Masculine." In German, the masculine gender is the only one that changes in the accusative case (den, einen, meinen). Naturally, the adjective follows suit. If the noun is masculine and it’s the direct object of the sentence, the ending is always -en.

Ich sehe den schwarzen Hund.

Ich habe einen schwarzen Hund.

Ich liebe meinen schwarzen Hund.

Notice a pattern? Everything ends in -en. Masculine accusative is the most "stable" inconsistency in the language.

Practical Application: How to Actually Use This

Stop trying to memorize the whole German adjective endings table in one sitting. It won't stick. Your brain isn't a hard drive; it's a muscle. You need to build "muscle memory" for specific phrases.

Start with the "Nominative Masc/Fem/Neut" for the ein category.

Ein guter Tag.

Eine gute Idee.

Ein gutes Bier.

Say those three phrases over and over until they feel natural. Don't move on to dative until these feel like second nature. The reason people fail is that they try to juggle all 48 possible combinations at once. Nobody can do that in the middle of a fast-paced conversation at a bakery in Berlin.

Nuance: Adjectives Without Endings

Sometimes, you don't need an ending at all. This happens when the adjective comes after the noun, usually following the verb sein (to be) or werden (to become).

Der Hund ist treu. (The dog is loyal.)

Das Wetter wird schön. (The weather is becoming beautiful.)

In these cases, the adjective stays in its "naked" or adverbial form. No -e, no -en, no nothing. This is why beginner courses start with these sentences—they let you avoid the German adjective endings table entirely. But eventually, you’ll want to describe the "loyal dog," and that’s when you have to step back into the grid.

Looking at the "Der-words" Beyond the Basics

Most textbooks tell you that "weak declension" applies to der, die, das. That’s true, but it also applies to words that behave like der. These are often called "determiners."

- Dieser (this)

- Jener (that)

- Jeder (every)

- Mancher (some)

- Welcher (which)

- Solcher (such)

If you use dieser, the adjective following it will take the exact same "weak" ending it would have taken after der.

Dieser alte Mann (This old man).

Der alte Mann (The old man).

The logic stays perfectly intact.

The Strategy for Mastery

Consistency beats intensity. Spend five minutes a day writing out five sentences using a specific corner of the adjective table. Focus on one case per week.

- Week 1: Nominative only. Focus on der/die/das vs ein/eine/ein.

- Week 2: Accusative. Pay special attention to how masculine nouns change.

- Week 3: Dative. Relish in the fact that almost everything is -en.

- Week 4: Strong declension (no articles). This is the "boss level."

By breaking it down, you stop seeing a wall of text and start seeing a system. German is a Lego set. Once you know how the pieces click together, you can build anything.

To truly internalize these patterns, your next step is to grab a German news article or a short story. Scan the text specifically for adjectives. Circle the adjective and the noun it describes. Then, look at the word immediately before the adjective. Ask yourself: Why does this adjective have an -en? Is it because of a dative preposition? Is it a masculine direct object? By reverse-engineering real-world German, you move beyond the static German adjective endings table and start understanding the living rhythm of the language. Start with a single paragraph today and find every adjective ending. It’s the most effective way to turn abstract grammar into an intuitive skill.