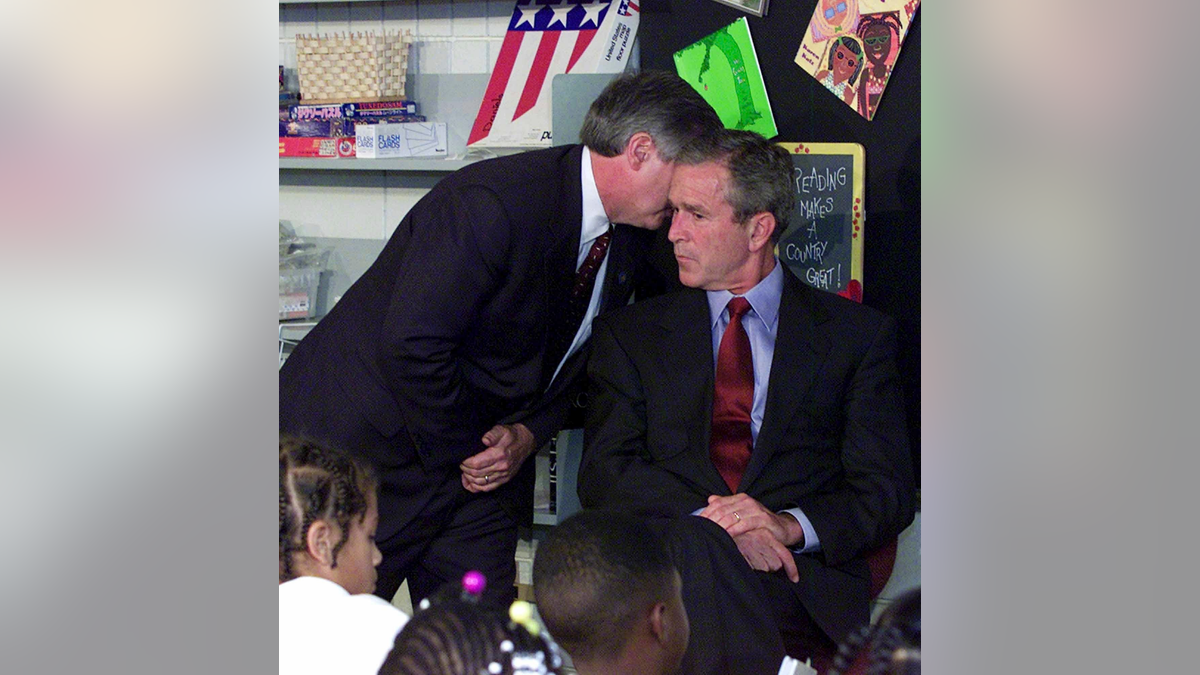

It’s an image burned into the collective memory of an entire generation. George W. Bush sits in a tiny plastic chair, a copy of The Pet Goat in his lap, while Andrew Card whispers into his ear. "A second plane hit the second tower. America is under attack." For seven minutes, the President of the United States stayed in that seat. He didn't jump up. He didn't bark orders. He just sat there.

People still argue about it today. Some see it as a failure of leadership—a moment of "frozen" indecision while the world burned. Others see it as a leader trying to remain calm for a room full of second graders so he didn't spark a stampede of panic. Honestly, the reality is a mix of both, caught in the weird, jarring transition between a routine photo-op and the start of a new era in global history.

The setup: Why was Bush in a classroom on 9/11 anyway?

September 11, 2001, was supposed to be a "soft" news day for the White House. The administration was pushing its "No Child Left Behind" initiative. To do that, they chose Emma E. Booker Elementary School in Sarasota, Florida. The goal was simple: highlight reading programs.

Bush arrived at the school just before 9:00 AM. He already knew a plane had hit the World Trade Center. He actually spoke to National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice about it before entering the classroom. But at that moment, everyone thought it was a small twin-engine plane—a tragic pilot error, maybe. Nobody knew it was a hijacked 767.

The President walked into Sandra Kay Daniels’ second-grade classroom. He was there to listen to the kids read. It was supposed to be a nice, easy morning.

The whisper that changed everything

The kids were reading a story about a goat. It's a phonics exercise, basically. Around 9:05 AM, Andrew Card, the White House Chief of Staff, entered the room. He didn't want to start a conversation. He walked up to Bush and whispered those eleven famous words.

"A second plane hit the second tower. America is under attack."

Bush’s expression changed. You can see it in the footage. His jaw tightens. His eyes glaze over for a second. But then? He stays. He picks the book back up. He follows along as the children continue to read "The... pet... goat."

It’s one of the most scrutinized seven minutes in the history of the American presidency. Critics, most notably Michael Moore in Fahrenheit 9/11, used this footage to suggest Bush was incompetent or paralyzed. But if you talk to the people in the room, the vibe was different.

Seven minutes of silence

Why didn't he leave?

👉 See also: How Old Is Celeste Rivas? The Truth Behind the Tragic Timeline

Bush later explained that he didn't want to rattle the kids. He wanted to project a sense of stability. Think about it. If the President of the United States suddenly bolts out of a room surrounded by Secret Service agents in a flurry of motion, what happens to the 18 children sitting three feet away? What happens to the press corps watching?

"I made a high-level decision," Bush said in a later interview. "I didn't want to do anything dramatic. I didn't want to flare out of the chair and scare the classroom. I wanted to wait for the appropriate moment to leave."

The teacher, Sandra Kay Daniels, has defended him for years. She said she knew something was wrong, but his calmness helped her keep the kids focused. It’s easy to armchair quarterback this twenty-plus years later. It’s a lot harder when you're the guy in the chair and your brain is trying to process that the country is literally being invaded while you're listening to a story about a farm animal.

The Secret Service perspective

The Secret Service gets a lot of heat for this too. Why didn't they grab him? Usually, if there's a threat, they move the "package" immediately.

But they didn't know if the school was a target. They didn't know where the threat was coming from. In those first few minutes, the communication was chaotic. They were scrambling to secure a perimeter while the President was in a highly public, glass-windowed environment. There’s a legitimate argument that staying put for a few minutes while they figured out the next move was actually the safer tactical choice than rushing him into an un-prepped motorcade.

What happened immediately after he left?

At 9:12 AM, Bush finally left the classroom. He didn't go to the kids. He went to a private room nearby that had been set up as a secure communication center.

He spoke to Vice President Dick Cheney. He spoke to Governor George Pataki of New York. He spoke to the FBI Director. He was scribbling notes on a legal pad. These were the first drafts of the speech he would give in the school’s library just a few minutes later.

By 9:30 AM, he was standing in front of a blue backdrop in the school library. He told the nation—and the world—that we had suffered a "national tragedy." He asked for a moment of silence. He looked tired. He looked like a man who had aged ten years in twenty minutes.

The legacy of the Booker Elementary visit

The image of Bush in the classroom on 9/11 has become a Rorschach test for American politics.

✨ Don't miss: How Did Black Men Vote in 2024: What Really Happened at the Polls

If you dislike him, you see a man who was "checked out" and lacked the instincts to lead during a crisis. You see a "deer in the headlights." If you support him, or at least view the moment through a lens of crisis management, you see a leader trying to prevent a panic.

It’s worth noting that Gwendolyn Tose'-Rigell, the school's principal, always maintained that Bush handled it correctly. She argued that the media turned a moment of human processing into a political weapon.

Behind the scenes: The "Angel" is airborne

While the classroom footage is what everyone talks about, the real drama happened right after they left the school.

Air Force One took off. But they didn't know where they were going. There were reports of a "high-speed target" heading toward the ranch in Crawford. There were rumors that Air Force One itself—code-named "Angel" that day—was a target.

Bush wanted to go back to Washington D.C. The Secret Service said absolutely not. They ended up zig-zagging across the country, stopping at Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana and then Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska.

The seven minutes in the classroom were just the start of a day where the President was effectively a nomad in the sky.

The "Pet Goat" misconceptions

People love to point out that the book was The Pet Goat. They make fun of it.

Actually, it wasn't a standalone book. It was a story in a reading program called Reading Mastery II: Days and Ways. It’s a phonics-based curriculum. The kids weren't just reading for fun; they were demonstrating their ability to decode sounds.

And for the record? Those kids did a great job. They were among the best readers in the district. It’s a weird, small detail, but those students—who are now in their early 30s—often talk about how surreal it is to have their childhood literacy milestone linked to the darkest day in modern American history.

🔗 Read more: Great Barrington MA Tornado: What Really Happened That Memorial Day

Lessons in crisis communication

What can we actually learn from this?

First, the "first report" is almost always wrong. Bush was told it was a small plane. He entered the room with the wrong information. In any crisis, the information you have at minute one is likely 50% garbage.

Second, optics matter, but they aren't everything. Bush was worried about the optics of scaring children. He wasn't worried about the optics of looking "slow" to the cameras. In the social media age, a politician today would probably jump up immediately because they are hyper-aware of how a "frozen" moment looks on a 10-second TikTok clip. In 2001, that wasn't the primary concern.

Third, there is a massive gap between "doing something" and "doing the right thing." Bolting out of the room three minutes earlier wouldn't have stopped the planes. It wouldn't have saved the Pentagon. By 9:05 AM, the damage was done. The next steps were about the response, not the immediate prevention.

Actionable insights for understanding the event

If you want to really understand the nuances of this moment, don't just watch the looped 30-second clip on YouTube.

- Watch the full 20-minute video: There is raw footage of the entire classroom visit. You can see the shift in the room's energy before and after Card enters.

- Read the 9/11 Commission Report: It specifically details the timeline of the President's movements. It’s dry, but it’s the most accurate account of the communication failures between the FAA and the White House.

- Listen to the "9/11 kids" interviews: Several of the students, like Lazaro Dubrocq and Kaycee Maresca, have given interviews as adults. They provide a perspective that the cameras couldn't catch—the feeling of the room from the floor level.

- Research "The Fog of War": This isn't just a catchy phrase. It’s a psychological state. Understanding how the human brain processes "black swan" events (events that are completely unexpected) helps explain why Bush—or anyone—would linger in a familiar task while processing an unthinkable reality.

The classroom visit remains a haunting vignette. It's the last moment of the "old world" before the "new world" started. It shows a President caught between his duty to be a "Comforter in Chief" for a few kids and his duty to be "Commander in Chief" for a nation under siege.

Whether those seven minutes were a mistake or a measured choice depends entirely on what you expect from a leader in the first few seconds of a nightmare. There's no consensus, and there probably never will be. But the facts show a man who was trying to hold it together while the world he knew was disappearing.

To understand the full scope of that day, you have to look past the "The Pet Goat" and look at the chaotic hours that followed on Air Force One. The classroom was just the quiet before the longest storm in American history.