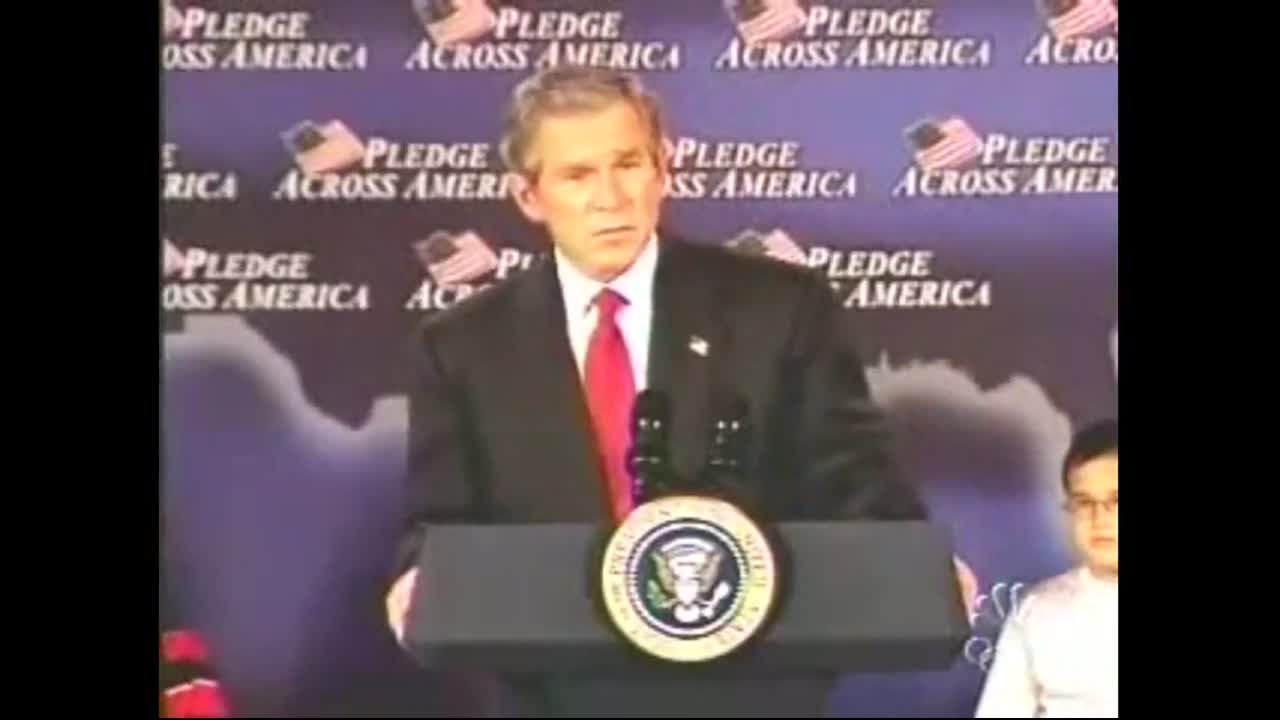

It was September 17, 2002. Nashville, Tennessee. President George W. Bush stood behind a podium at East Literature Magnet School, ready to talk about education and the "No Child Left Behind" Act. He was in his element, or so it seemed. Then, it happened. He started a sentence about trust, pivoted toward an old Texas proverb, and halfway through, the wheels just fell off the wagon. The result was a linguistic train wreck that would define his presidency more than almost any policy paper ever could.

"There's an old saying in Tennessee—I know it's in Texas, probably in Tennessee—that says, fool me once, shame on—shame on you. Fool me—you can't get fooled again."

The crowd chuckled. The press corps scribbled. Within hours, George W. Bush fool me once became a global punchline. But if you look closer at the footage, you see a man who realized mid-sentence that he was about to give his political enemies a gift-wrapped soundbite of him saying the words "shame on me." He chose a clunky, nonsensical exit strategy instead.

Honestly, it’s arguably the most analyzed "Bushism" in existence. While some saw it as proof of a lack of intellectual depth, others saw it as a momentary lapse in a high-pressure environment. It wasn't just a mistake; it was a cultural phenomenon that signaled the beginning of the "viral" era of political gaffes.

The Anatomy of the Gaffe: What Actually Happened in Nashville?

Most people remember the clip, but they don't remember the context. Bush was trying to make a point about accountability in schools. He was trying to sound folksy, a trademark of his political brand. The "fool me once" proverb is simple enough: "Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me."

Why did he stop? If he had finished the proverb correctly, he would have had to say "shame on me" while staring directly into a dozen television cameras. In the world of political optics, that is a cardinal sin. You never want a clip of yourself saying "shame on me" available for an opponent's attack ad. He caught himself. You can see the gears turning. He hesitated, his eyes darted, and then he landed on "you can't get fooled again"—likely a subconscious pull from The Who’s famous rock anthem.

He survived the moment, but the cost was high. It reinforced a specific narrative. Since his days as Governor of Texas, critics had painted Bush as a man struggling with the English language. This moment solidified it. It didn't matter that he had graduated from Yale and Harvard Business School. The "fool me once" moment became the primary piece of evidence for the "he’s not that bright" camp.

The Psychology of a Public Slip

Psycholinguistics is a weird field. When we speak, our brains are usually several words ahead of our mouths. Dr. Geoffrey Beattie, a psychologist who has studied the speech patterns of public figures, often notes that under high stress, the "monitoring" phase of speech—where we check for errors—can override the "execution" phase.

💡 You might also like: Why a Man Hits Girl for Bullying Incidents Go Viral and What They Reveal About Our Breaking Point

Bush was a fast talker. He liked to get to the point. When the monitoring system signaled "Danger! Don't say 'shame on me'!" he didn't have a backup plan ready. He improvised. And he failed.

Beyond the Joke: Why This Matters for Political Strategy

If you think this was just a funny mistake, you're missing the bigger picture of how political communication changed after 2002. Before this, a gaffe might make the evening news and then vanish. But the George W. Bush fool me once clip arrived right as the internet was becoming a daily staple. It lived on early video-sharing sites and was passed around via email chains.

It changed how speechwriters worked.

- They started writing shorter, punchier sentences.

- They avoided complex metaphors that could be easily mangled.

- They became obsessed with "soundbite safety."

If you look at modern political speeches from figures like Barack Obama or even later Republicans, you see a much more rhythmic, almost cautious approach to phrasing. No one wants to be the next "fool me once" guy.

The Pop Culture Explosion

The legacy of this gaffe is massive. It wasn't just Saturday Night Live (though Will Ferrell basically built a career on it). It seeped into music. J. Cole famously sampled the audio in his hit song "No Role Modelz."

"There's an old saying in Tennessee—I know it's in Texas, probably in Tennessee—that says, fool me once, shame on—shame on you. Fool me—you can't get fooled again."

By putting those words over a beat, J. Cole introduced the gaffe to a generation that wasn't even born when Bush was in office. It turned a political mistake into a permanent fixture of hip-hop culture. It’s a rare feat. Most political gaffes have the shelf life of an open gallon of milk. This one is more like honey; it literally never spoils.

📖 Related: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

Comparing Bushisms: Was This the Peak?

Bush had plenty of other linguistic adventures. He gave us "misunderestimated." He talked about "wings take dream." He once asked, "Is our children learning?"

But the George W. Bush fool me once moment is the undisputed king. Why? Because it’s relatable. Everyone has started a sentence they didn't know how to finish. Everyone has tried to sound smart and ended up sounding like a total goof.

The Strategy of Folksiness

It’s worth noting that many people believe Bush’s "folksiness" was partly intentional. It made him seem like someone you could have a beer with—a key metric in the 2000 and 2004 elections. By stumbling over his words, he seemed less like a "Washington elite" and more like a regular guy from the ranch.

Whether the Nashville slip was a calculated "regular guy" moment or a genuine brain-fart is still debated in political science circles. Most insiders from the Bush administration, like former Press Secretary Ari Fleischer, have largely played it down as a simple tired moment during a long travel schedule. But the public perception remains: it was a window into the man’s soul, or at least his vocabulary.

How to Avoid Your Own "Fool Me Once" Moment

In 2026, we live in a world of "hot mics" and "always-on" cameras. Whether you're a CEO, a local politician, or just someone giving a wedding toast, the lessons from George W. Bush are actually pretty practical.

1. Don't use proverbs you haven't practiced.

Proverbs are linguistic traps. If you miss one word, the whole thing collapses. If you aren't 100% sure of the wording, just say what you mean in plain English.

2. The Power of the Pause.

If Bush had just stopped for two seconds when he realized he was in trouble, he could have recovered. A pause looks like "thoughtfulness" on camera. Rambling looks like "confusion."

👉 See also: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

3. Lean into it.

If you mess up, own it immediately. If Bush had laughed and said, "Well, I think I just mangled that one, didn't I?" the story would have died the next day. The fact that he pushed through it with a straight face made it legendary.

The Long-Term Impact on Truth and Trust

There’s a darker side to the humor. Some historians argue that the constant focus on Bush’s verbal slips distracted from serious policy debates regarding the Iraq War and the Patriot Act. While the public was laughing at "you can't get fooled again," the administration was making massive, world-altering decisions.

It highlights a flaw in our media diet. We prioritize the "viral" over the "vital." A 10-second slip of the tongue shouldn't outweigh a 100-page economic policy, but in the attention economy, the slip wins every time.

What Most People Get Wrong

People think Bush didn't know the saying. That’s almost certainly false. He had used similar "Texas-isms" throughout his life. The error was a collision between his internal PR filter and his external speech delivery. It was a technical glitch in the human brain, not a lack of knowledge of a very common phrase.

Also, the "Tennessee" vs "Texas" part of the quote is often ignored, but it’s actually the weirdest part. Why would he think a universal English proverb was specific to those two states? That speaks more to his desire to "localize" his appeal than to his inability to remember the words.

Moving Forward: The Legacy of the Gaffe

Today, the "Bushisms" are viewed with a certain sense of nostalgia by some, especially compared to the much more aggressive political rhetoric of the 2020s. They seem almost quaint. But the George W. Bush fool me once moment remains a masterclass in how a single moment can define a legacy.

If you're looking to understand the intersection of personality, politics, and the internet, this is the ground zero. It taught us that in the digital age, your mistakes are permanent, your stumbles are content, and once you've fooled the public with a good laugh, they'll never let you forget it.

To truly learn from this, one should look at the transcripts of the entire Nashville speech. You'll see a man who was actually quite coherent for 99% of the time. But that 1% is what matters. In the history books of the future, George W. Bush will have chapters on 9/11 and the Great Recession, but in the footnotes of our collective memory, he will always be the man who couldn't be fooled again.

Practical Steps for Public Speakers

- Record yourself: You probably have verbal tics you don't know about. Bush didn't realize how often he swapped vowels until he saw it on the news.

- Simplify the script: If a sentence is longer than 20 words, cut it in half.

- Have an "Exit Strategy": If you lose your place, have a go-to phrase to reset, like "Let me put that another way" or "The bottom line is this."

- Embrace the human element: If you do mess up, don't panic. Human error is actually a great way to build rapport with an audience, provided you handle it with a bit of grace and a self-deprecating smile.

The "Fool Me Once" incident wasn't a tragedy, and it wasn't a triumph. It was just human. In an era of AI-generated perfection and highly polished personas, there's something almost refreshing about a mistake so spectacularly weird that it could only come from a real, breathing, and slightly flustered human being.