He was drunk. That’s the starting point for almost every legendary story involving George Jones, but by the time 1980 rolled around, the drinking had transitioned from a rowdy habit into a full-blown haunting. Jones was at his commercial peak with "He Stopped Loving Her Today," yet he was physically and mentally falling apart. Then came a song about a different kind of ghost. The King Is Gone by George Jones isn't just a kitschy novelty track about Elvis Presley; it’s a bizarre, heartbreaking window into the psyche of a man who saw his own reflection in a shattered decanter.

Music critics often dismiss the song. They see the title—sometimes listed as "Ya Ba Da Ba Do (So Are You)"—and assume it's a joke. It isn't. Not really. When George stood in front of the mic to record this, he wasn't just singing about a plastic Elvis bottle. He was singing about the loneliness of being a living legend when you feel like you’re already dead.

The Weird History of the Elvis Decanter Song

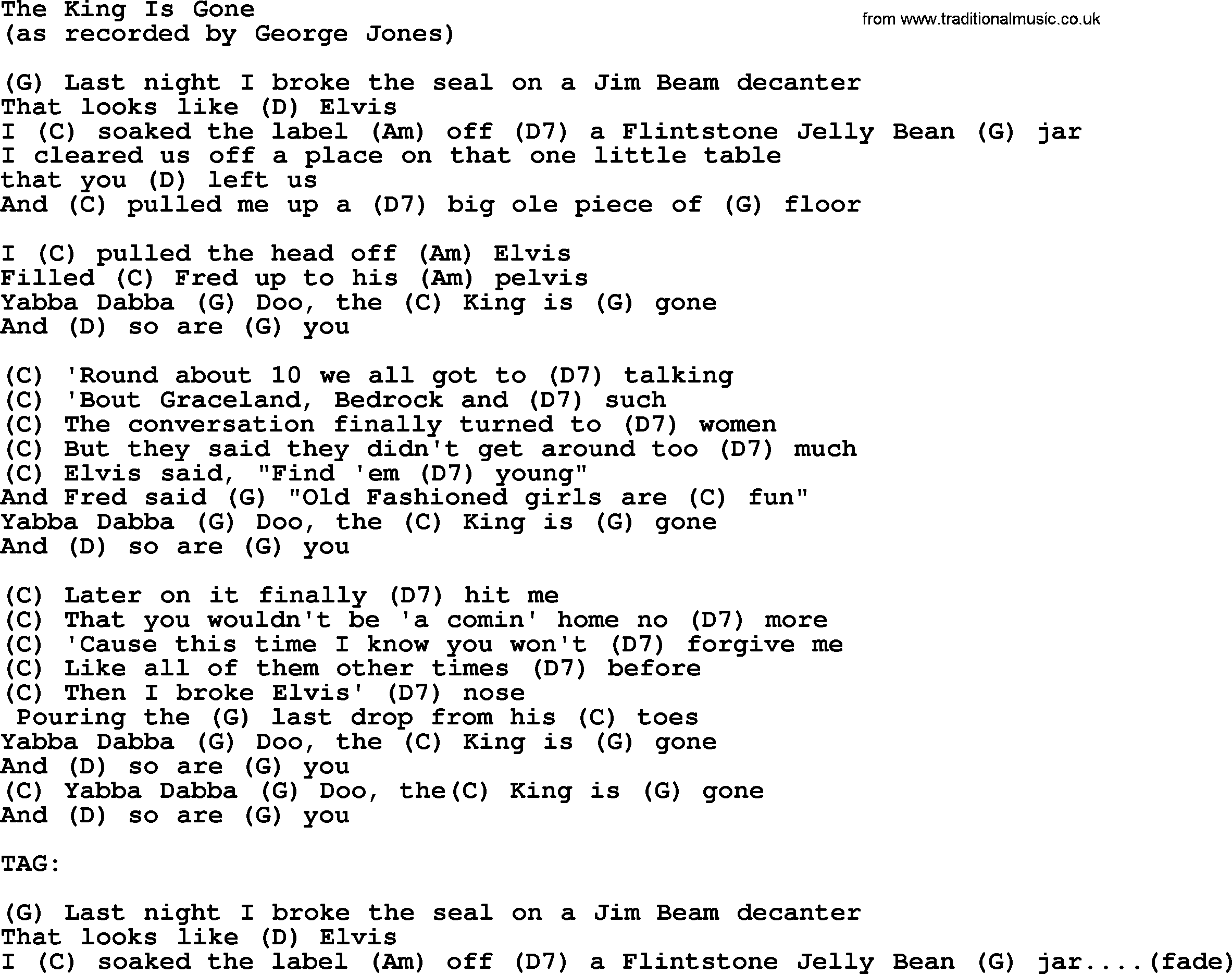

The song was written by Ronnie McDowell and Bobby Cochran. McDowell, of course, made his entire career out of being an Elvis devotee, hitting it big with "The King Is Dead" just weeks after Presley passed in 1977. But for George Jones, the song took on a darker, more personal resonance. The narrative is simple: a man sits alone, drinking "bourbon from a Dixie cup," staring at a ceramic Elvis Presley decanter.

He’s talking to the bottle.

Think about that for a second. George Jones, arguably the greatest country singer to ever live, was recording a song where he confesses to having a deep, philosophical conversation with a piece of Jim Beam memorabilia. It sounds ridiculous on paper. But listen to the phrasing. When George sings the line about the decanter having a "look of sadness on its face," he isn't acting. He spent the late 70s talking to his own shadow, hiding under tour buses, and speaking in a "Duck" voice to escape his own reality.

Why the Flintstones are in a Country Song

The hook of The King Is Gone by George Jones is what throws people off. The "Ya Ba Da Ba Do" line. It's a reference to a Fred Flintstone jelly glass that the narrator is using as a chaser. It’s a jarring juxtaposition. You have the high tragedy of Elvis Presley—the King of Rock and Roll—being used as a vessel for cheap whiskey, and then you have a cartoon character from a jelly jar.

👉 See also: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

It’s pure Americana. It captures that specific brand of rural loneliness where your only friends are the brand names on your kitchen counter. Honestly, it’s one of the most honest depictions of alcoholism ever put to vinyl, even if it feels like a gimmick at first.

The "Possum" vs. The "King"

George and Elvis never actually recorded together, which is a tragedy of history. They were two sides of the same coin. Elvis was the flash, the pelvis, the movie star who died under the weight of his own image. George was the raw, unpolished nerve of the South. While Elvis was being draped in capes in Vegas, George was missing shows and getting arrested on lawnmowers.

When Jones released this track on his I Am What I Am album, he was acknowledging the hierarchy. By calling Elvis "The King," Jones was positioning himself as the survivor. But the irony was thick. At the time, George was so unreliable that promoters were afraid to book him. He was "No Show Jones." In a way, the song is a dialogue between two men who were destroyed by their fans' expectations. One was gone; the other was trying his best to follow him into the grave.

The Production Secrets of the 1980 Sessions

Billy Sherrill, the legendary producer behind the "Countrypolitan" sound, was the man who had to corral George into the studio. Sherrill knew how to use George's voice as an instrument of pure sorrow. In the recording of The King Is Gone by George Jones, you can hear the restraint. Sherrill didn't overproduce it with too many strings. He let the steel guitar weep behind George’s weary delivery.

Interestingly, the session musicians on that album were the elite "A-Team" of Nashville. We’re talking about Hargus "Pig" Robbins on piano and Jerry Reed occasionally stopping by. They treated this song with a weird reverence. They knew that if anyone else sang a song about a Fred Flintstone glass, it would be a comedy. But because it was George, it was a funeral march.

✨ Don't miss: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

What People Get Wrong About the Lyrics

There is a common misconception that the song is a tribute. It’s not. A tribute honors the life of someone. This song is about the absence of someone. It’s about the vacuum left behind when a cultural icon dies and all we have left are the plastic trinkets and the booze inside them.

- The Bourbon: The narrator mentions "the King is gone but I don't feel alone." This is a lie. The entire song is a study in isolation.

- The Decanter: In the 1970s, McCormick and other distilleries released actual Elvis decanters. They are collector's items now. George was singing about a very real object that sat on thousands of wood-paneled bars across the South.

- The Ending: The way George lingers on the final notes isn't celebratory. It’s the sound of a man who has finished the bottle and realized he still has to wake up tomorrow.

Why It Still Works in 2026

You’d think a song with a Flintstones reference would age like milk. It hasn't. In the age of digital nostalgia, The King Is Gone by George Jones feels strangely modern. We are still obsessed with the objects of our dead idols. We still use substances to bridge the gap between our reality and the legends we grew up with.

Listen to the vocal "slur" George puts on the word "King." It’s subtle. It’s a masterclass in vocal acting. George Jones didn't just sing songs; he inhabited them. He lived inside the lyrics until they became his own truth. If you’ve ever felt like the world moved on without you, or if you’ve ever looked at a photograph of a lost loved one and felt a physical ache, this song hits. It doesn't matter if it's Elvis or a neighbor; the feeling of "the king is gone" is universal.

The Impact on Country Music

This track helped solidify the "I Am What I Am" era as the definitive George Jones period. It proved he could take "lesser" material—songs that might be considered B-sides for others—and turn them into gold. It paved the way for the neo-traditionalist movement of the 80s. Artists like George Strait and Randy Travis looked at what Jones did here and realized you didn't need to be flashy. You just needed to be real. Even when you're talking to a bottle.

Actionable Insights for Music Lovers and Collectors

If you're looking to truly appreciate this era of country music or if you're a vinyl hunter trying to find the best version of this story, there are a few things you should actually do. Don't just stream it on a tinny phone speaker.

🔗 Read more: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Find the Original Vinyl Pressing

The 1980 Epic Records pressing of I Am What I Am is the only way to hear the warmth of the low end. Digital remasters often clip the delicate steel guitar work that makes "The King Is Gone" feel so lonely. Look for the "Sterling" stamp in the dead wax—that’s the one mastered by Ted Jensen.

Listen for the Breath

One of the most human things about George Jones’s recordings is his breathing. In this specific track, you can hear him take a sharp breath before the "Ya Ba Da Ba Do" line. It’s the sound of a man bracing himself. In modern music, engineers edit those breaths out. Don't. They are part of the story.

Track the Elvis Decanters

If you’re a memorabilia nerd, look for the "McCormick Elvis Gold Leaf" decanters from 1977. Those are the specific ones referenced in the song. Seeing the physical object—the hollowed-out head of Presley—makes the lyrics hit a lot harder. It transforms the song from a story into a historical document.

Compare the Live Versions

Search for live footage of George performing this in the early 80s. You’ll notice he often changed the phrasing depending on how "lit" he was that night. Sometimes he’d emphasize the comedy; other times, he’d barely get through it without sounding like he was going to break down. That variability is what made George Jones the greatest. He never gave the same performance twice because he never felt the same way twice.

The legacy of this song isn't in the charts or the kitsch. It's in the honesty. It’s the reminder that even the biggest stars in the world eventually end up as empty bottles, and the only thing that lasts is the voice left behind on the tape.

Check your local record shops for the I Am What I Am LP. It usually sits in the "J" section for about ten bucks. It’s the best ten dollars you’ll ever spend if you want to understand the soul of Nashville.