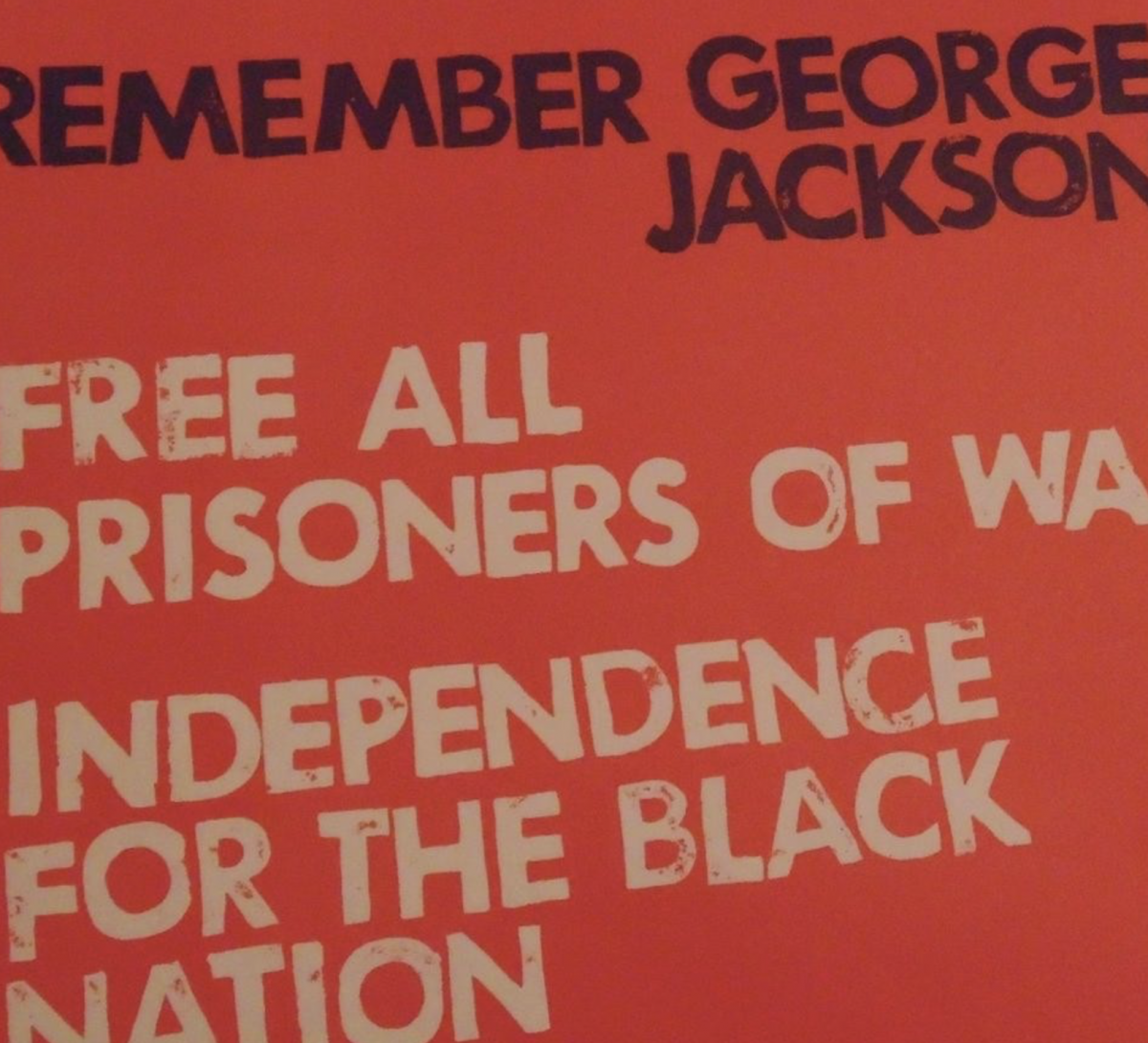

You’re sitting in a cramped cell in San Quentin. You’ve been down for over a decade for a seventy-dollar gas station robbery. The system keeps moving the goalposts on your parole. Most people would break. Some would just rot. George Jackson? He wrote. He studied. He organized. He became a general.

When people talk about George Jackson Blood in My Eye, they usually treat it like a dusty relic of 1970s radicalism. They’re wrong. This isn't just a book. It’s a snapshot of a man who knew he was going to die. Jackson finished the manuscript only days before he was killed during an alleged escape attempt on August 21, 1971. That context matters. It’s not a polite academic treatise on political science; it’s a manual for revolution written in the shadow of the gun.

It’s raw. It’s angry. It’s incredibly smart.

The Man Behind the Manuscript

George Jackson wasn't born a revolutionary. He was a kid from Chicago who moved to Los Angeles and got caught up in the gears of the California penal system. In 1960, he was accused of being an accessory to a gas station robbery. His lawyer told him to plead guilty to get a light sentence. Instead, he got "one year to life." That indeterminate sentence meant the parole board held his entire existence in their hands. They never let him go.

While inside, Jackson transformed. He didn't just lift weights; he devoured Marx, Mao, and Fanon. He co-founded the Black Guerrilla Family. By the time he wrote Soledad Brother, he was a celebrity. But George Jackson Blood in My Eye is different. It’s colder. More clinical. It’s where he stops explaining his life and starts explaining his strategy for dismantling what he called the "monster."

He saw the prison not as a place for criminals, but as a microcosm of the United States. To him, the walls, the guards, and the indeterminate sentences were just the most honest versions of the social control used against Black Americans everywhere.

What George Jackson Blood in My Eye Actually Says

Most readers expect a memoir. They get a punch in the throat. Jackson spends a huge chunk of the book analyzing fascism. But he doesn't define fascism the way a history textbook does—he’s not just talking about Mussolini or Hitler. He argues that the U.S. had already entered a stage of "clandestine fascism."

💡 You might also like: Robert Hanssen: What Most People Get Wrong About the FBI's Most Damaging Spy

He believed the state had become so good at absorbing dissent that it didn't need to wear a uniform all the time. It used consumerism, media, and a massive police apparatus to keep people in line. If you stepped out of line? You ended up where he was.

The Concept of the Vanguard

Jackson was obsessed with the idea of the "vanguard." In his view, the revolution wouldn't start with a mass movement of millions of people holding hands. It would start with small, dedicated groups—often within the prison system—who would force the state to show its true, violent face. He called for a "people’s army."

He writes about the need for total commitment. You can’t be a part-time revolutionary. You can’t just show up to a protest on Saturday and go back to your desk job on Monday. For Jackson, the struggle was total. He famously wrote about how the "pre-revolutionary" stage was over. He thought the shooting had already started, whether people realized it or not.

A Different Kind of Language

The prose in George Jackson Blood in My Eye is jagged. It’s a mix of high-level Marxist theory and the gritty vernacular of a man who had been in solitary confinement for years.

Honestly, it can be a tough read. Not because the words are big, but because the stakes are so high. He’s talking about urban guerrilla warfare in the middle of a letter to his lawyer or a comrade. He’s dissecting the failures of the "Old Left" while hearing the keys of the guards rattling outside his door.

Why It Still Scares People

There’s a reason this book doesn't show up on many "Must-Read" lists in mainstream bookstores. It’s dangerous. It doesn't ask for reform. It doesn't ask for "a seat at the table." It wants to flip the table over and burn the building down.

📖 Related: Why the Recent Snowfall Western New York State Emergency Was Different

Critics often point to Jackson’s embrace of violence as a dealbreaker. They see it as nihilistic. But if you look at the era—the assassinations of Fred Hampton and MLK, the Vietnam War, the COINTELPRO operations—Jackson’s worldview starts to look less like paranoia and more like a reaction to a very specific, very violent reality. He wasn't advocating for violence because he liked it. He argued that the state had left no other options on the table.

The August 21 Incident

You can’t talk about George Jackson Blood in My Eye without talking about how it ended. On August 21, 1971, Jackson was killed in San Quentin. The official story is that he had a 9mm pistol smuggled into the prison inside a wig. He supposedly took over a cellblock, released prisoners, and was shot while running across the yard.

A lot of people don't buy it.

The logistical impossibility of hiding a full-sized pistol in a wig has been debated for decades. Some say it was an execution. Others say it was a desperate, planned suicide-mission by a man who knew he’d never be free. Regardless of what happened in that yard, the death of George Jackson turned him into a martyr. It triggered the Attica Prison Riot just weeks later. The inmates at Attica wore black armbands. They knew exactly who he was.

The Legacy of the "Soledad Brother"

So, does it matter today?

If you look at the modern prison abolition movement, Jackson’s fingerprints are everywhere. When activists talk about the "school-to-prison pipeline" or "mass incarceration as a form of social control," they are essentially paraphrasing George Jackson Blood in My Eye. He was one of the first to articulate that the prison system isn't "broken"—it’s working exactly as intended.

👉 See also: Nate Silver Trump Approval Rating: Why the 2026 Numbers Look So Different

He challenged the idea that some people are "criminals" while others are just "citizens." He saw the line between the two as a political tool used by those in power.

Key Takeaways from the Text

- Fascism is Adaptive: Jackson argues that fascism doesn't always look like a dictatorship; it can look like a democracy that has perfected the art of repression.

- The Power of the Lumpenproletariat: Unlike some Marxists who focused only on factory workers, Jackson saw the "outcasts"—the prisoners, the unemployed, the street-level hustlers—as the real engine of change.

- The Unity of Theory and Action: Thinking isn't enough. Writing isn't enough. For Jackson, if your ideas don't lead to direct action, they are worthless.

How to Approach the Book Today

If you're going to pick up a copy of George Jackson Blood in My Eye, don't just read it as a history book. Read it as a primary source from a war zone.

You’ll find things you disagree with. You’ll probably find things that make you uncomfortable. Jackson was a man of his time—hyper-masculine, uncompromising, and deeply radicalized by a brutal environment. But you’ll also find a level of intellectual rigor that is rare in modern political discourse. He wasn't a "thug" who happened to read; he was an intellectual who was treated like a animal and decided to bite back.

The book is basically a final testament. It’s the "how-to" guide for a revolution he knew he wouldn't live to see.

Actionable Steps for Deepening Your Understanding

To truly grasp the weight of Jackson's work and its impact on modern thought, consider these specific avenues of exploration:

- Compare the Texts: Read Soledad Brother first. It’s more personal and helps you understand the man. Then read George Jackson Blood in My Eye to see how that personal pain was forged into a political weapon.

- Research COINTELPRO: To understand why Jackson was so convinced the state was out to kill him, look into the FBI's Counterintelligence Program. The documents are public now. It wasn't a conspiracy theory; it was a policy.

- Study the Attica Uprising: Look at the demands of the Attica prisoners in 1971. See how many of their grievances align with the critiques Jackson makes in his final book.

- Examine the Indeterminate Sentence: Research how California's sentencing laws worked in the 1960s. Understanding the "one year to life" trap explains the desperation and urgency in Jackson's writing.

- Look into Modern Abolitionist Literature: Authors like Angela Davis (who was a close friend of Jackson and even faced trial for her supposed connection to the courthouse shootout involving his brother, Jonathan) provide a contemporary bridge to these ideas.

The story of George Jackson isn't a happy one. It's a story of a brilliant mind trapped in a cage until it eventually burned out. But the sparks from that fire are still landing on people today. Whether you agree with his tactics or not, ignoring his analysis means missing a huge piece of the puzzle that explains why the American prison system looks the way it does.

Jackson didn't write for the critics or the historians. He wrote for the people in the cells next to him. And fifty years later, they’re still reading.