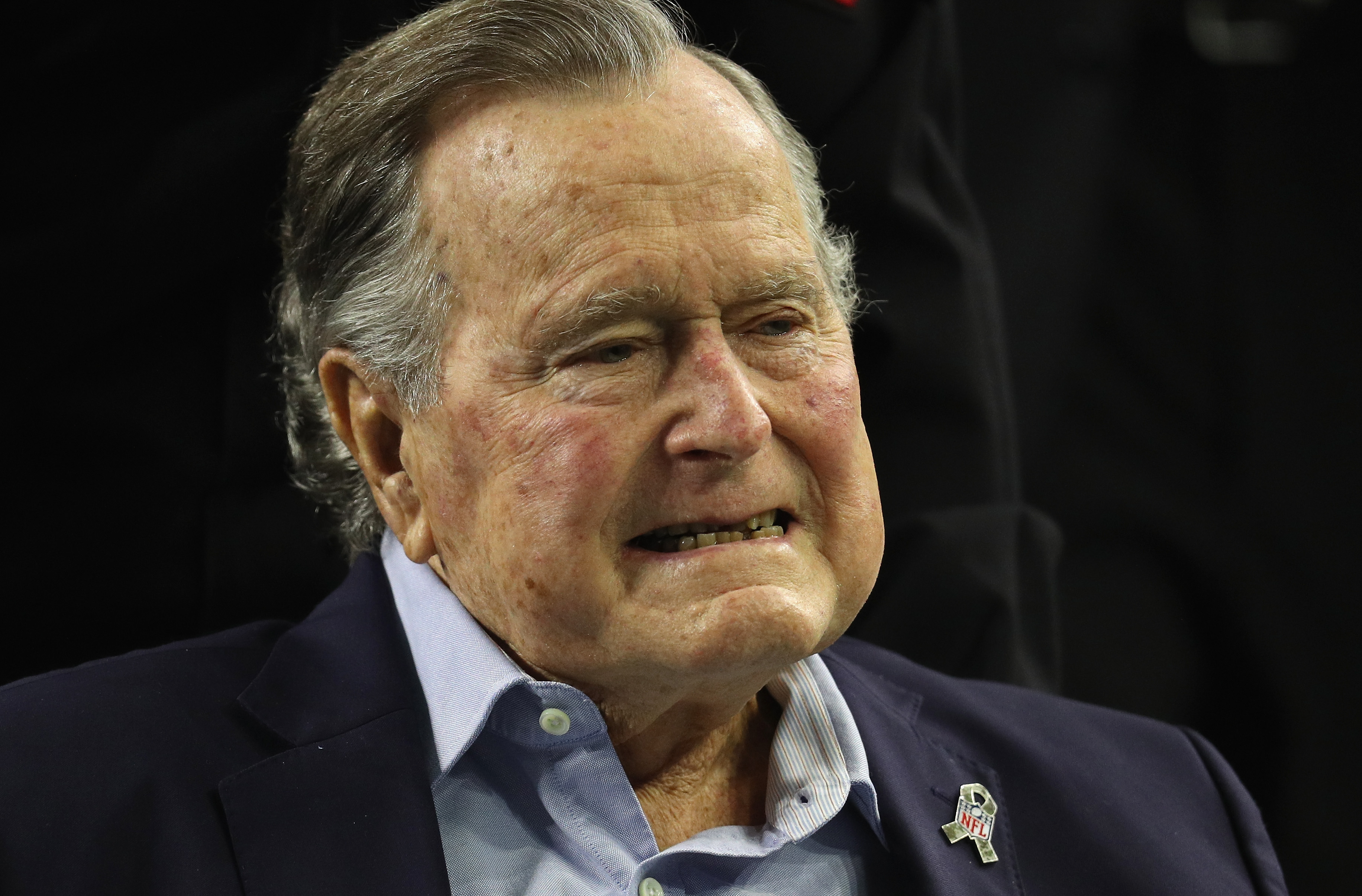

He was the last of the Greatest Generation to sit in the Oval Office. When the news broke that George HW Bush had died at age 94, it felt like more than just the passing of a former president. It felt like the closing of a specific chapter in American history. A lot of people forget that by the time November 30, 2018, rolled around, Bush had become a sort of grandfather figure to the nation, regardless of how they felt about his policies in the early '90s. He died at his home in Houston, surrounded by family, only months after his wife of 73 years, Barbara, had passed away.

Honestly, the timing was poetic in a way that most political lives aren't.

He had lived with a form of Parkinson’s disease for years. It kept him in a wheelchair, but it didn't stop him from skydiving on his 90th birthday or wearing those famously loud, colorful socks that became his late-life trademark. When a man lives to be 94, you expect the end, but the reality of George HW Bush’s death still hit the news cycle like a ton of bricks. It sparked a week of national mourning that felt surprisingly unified during a very divided time in the country.

The logistics of a state funeral and that famous train ride

The death of a president isn't just a private family matter; it’s a massive federal operation. Code-named "Operation Unified Reliance," the plans for this event had been sitting in a binder for years, constantly updated. You've got the lying in state at the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, the service at the National Cathedral, and the final trip back to Texas.

But what most people actually remember isn't the stuffy ceremonies in D.C. It was the train.

📖 Related: What Really Happened With Trump Revoking Mayorkas Secret Service Protection

Union Pacific 4141. It was a locomotive painted to look like Air Force One. Bush had seen it years prior and basically said, "I want that to take me home." It traveled 70 miles from Houston to College Station, where he was buried at his presidential library. Thousands of people lined the tracks. They weren't just standing there; they were waving flags, holding up kids, and some even placed coins on the tracks to be flattened by the wheels—a classic bit of Americana that felt perfectly in line with who Bush was.

Why the "Thousand Points of Light" mattered again

During the eulogies, especially the one given by his son, George W. Bush, there was a lot of talk about his "thousand points of light" philosophy. People used to mock that phrase. They thought it was too soft or vague. But after his death, the tone shifted. Experts like Jon Meacham, who wrote the definitive biography Destiny and Power, pointed out that Bush’s brand of "kinder, gentler" politics was actually a deeply held belief in civic duty.

He was a guy who wrote letters. Constant, handwritten notes to friends, enemies, and strangers. That’s a dead art.

When you look back at the footage of the funeral, you see every living president sitting in the same row. It was a rare moment of decorum. Even though Bush lost his re-election bid to Bill Clinton in 1992, the two became incredibly close later in life, working together on tsunami and hurricane relief. That friendship is probably the most enduring part of his legacy. It showed that the "death of a presidency" doesn't have to mean the death of a relationship.

👉 See also: Franklin D Roosevelt Civil Rights Record: Why It Is Way More Complicated Than You Think

George HW Bush’s death and the end of a certain type of leadership

There is a lot of debate about his foreign policy—Panama, the Gulf War, the end of the Cold War—but his passing forced a re-evaluation of his temperament. He was the last president to have served in combat during World War II. He was shot down over the Pacific. He survived when his crewmates didn't.

That experience defined him.

He didn't like the "vision thing." That's what he called it. He was a pragmatist. Critics often argued he was too cautious, while supporters saw him as a steady hand that navigated the collapse of the Soviet Union without a nuclear disaster. When he died, historians like Michael Beschloss noted that we were losing the last of the leaders who viewed government service as a humble obligation rather than a platform for celebrity.

The medical reality of his final years

It wasn't just old age. Bush had vascular parkinsonism. It’s a condition caused by small strokes that mimics Parkinson’s disease. It mostly affects the lower body, which is why he lost his ability to walk. Despite the physical decline, his mind stayed sharp for a remarkably long time.

✨ Don't miss: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

His last words were reportedly spoken to his son over the phone. George W. told him he had been a wonderful father and that he loved him. The elder Bush simply replied, "I love you, too."

That was it.

Moving forward: How to engage with this history

If you’re looking to really understand the impact of this era beyond the headlines, you shouldn't just read his Wikipedia page. There are better ways to get the "vibe" of the man and the moment.

- Visit the George HW Bush Presidential Library in College Station. It’s not just a building; it’s where he and Barbara are buried next to their daughter Robin, who died of leukemia at age three. Seeing the gravesite gives you a much better sense of the family’s private grief than any news broadcast.

- Read his letters. There is a book called All the Best, George Bush. It’s a collection of his correspondence from age 18 to 80. It’s probably the most honest look at a politician’s inner life ever published because he didn't write them for a book—he wrote them to people.

- Watch the Union Pacific 4141 documentary footage. It’s available online and captures that 70-mile journey. It’s a masterclass in how a nation says goodbye to a leader without the typical political shouting matches.

Understanding George HW Bush’s death requires looking at the transition of the Republican party and the shift in American culture from the mid-20th century to the digital age. He was a bridge between those two worlds. Whether you agreed with his "no new taxes" flip-flop or his handling of the ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act), his passing marked a definitive boundary in the American timeline. We aren't in that era anymore, for better or worse.

The best way to honor that history is to look at the primary sources—the letters, the legislative records, and the quiet moments of bipartisanship that followed his departure from the public stage.