It is easily the quietest moment on the wildest album ever made. You’ve just endured the chaotic, proto-metal shredding of "Helter Skelter." Your ears are literally ringing. Then, out of the static, comes this ghostly, fragile wisp of a song that sounds like it’s being played in a cathedral at three in the morning. That’s Long Long Long. It’s the second-to-last track on Disc 2 of the White Album, tucked right before the orchestral "Revolution 9" and the lullaby "Good Night."

Most people skip it. They shouldn’t.

If you look at the tracklist of The Beatles, usually just called the White Album, George Harrison’s contributions are heavy hitters. You have "While My Guitar Gently Weeps," which is a radio staple. You have "Piggies," which is weird and biting. But "Long Long Long" is where George actually found his voice as a solo artist before he even went solo. It’s a prayer. It’s a confession. It’s also a technical accident that became one of the coolest sounds in rock history.

Why Long Long Long is the Most Overlooked Beatles Masterpiece

George was in a strange place in 1968. The band was falling apart, or at least fraying at the edges. They had just come back from Rishikesh, India. While John was getting cynical and Paul was busy being a perfectionist, George was deep into a spiritual awakening that would define the rest of his life.

The song is structurally simple but emotionally heavy. It’s built on a three-chord progression that feels like it’s swaying in the wind. Honestly, it’s one of the few Beatles songs that feels truly vulnerable. There’s no swagger here. No "mop-top" energy. Just a man trying to find his way back to something he lost.

People often mistake it for a love song about a woman. It’s not. Well, not exactly. George later confirmed in his autobiography, I Me Mine, that the "you" he’s singing about is God. But he wrote it like a lost lover returning home. That ambiguity is what makes it work for everyone. Whether you’re religious or just someone who finally found a lost friend, the line "How could I ever have lost you / When I loved you" hits like a ton of bricks.

The Bob Dylan Connection

Did you know the melody is basically a reworked version of a Bob Dylan song? George was a massive Dylan fan—they were close friends until George passed away. He took the chord progression from "Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands" off Blonde on Blonde, but he slowed it down to a crawl. He stripped away the rambling folk-rock energy and turned it into a waltz.

👉 See also: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

It’s a 3/4 time signature. That’s why it feels like it’s circling. It doesn’t march forward like a standard 4/4 pop song. It drifts.

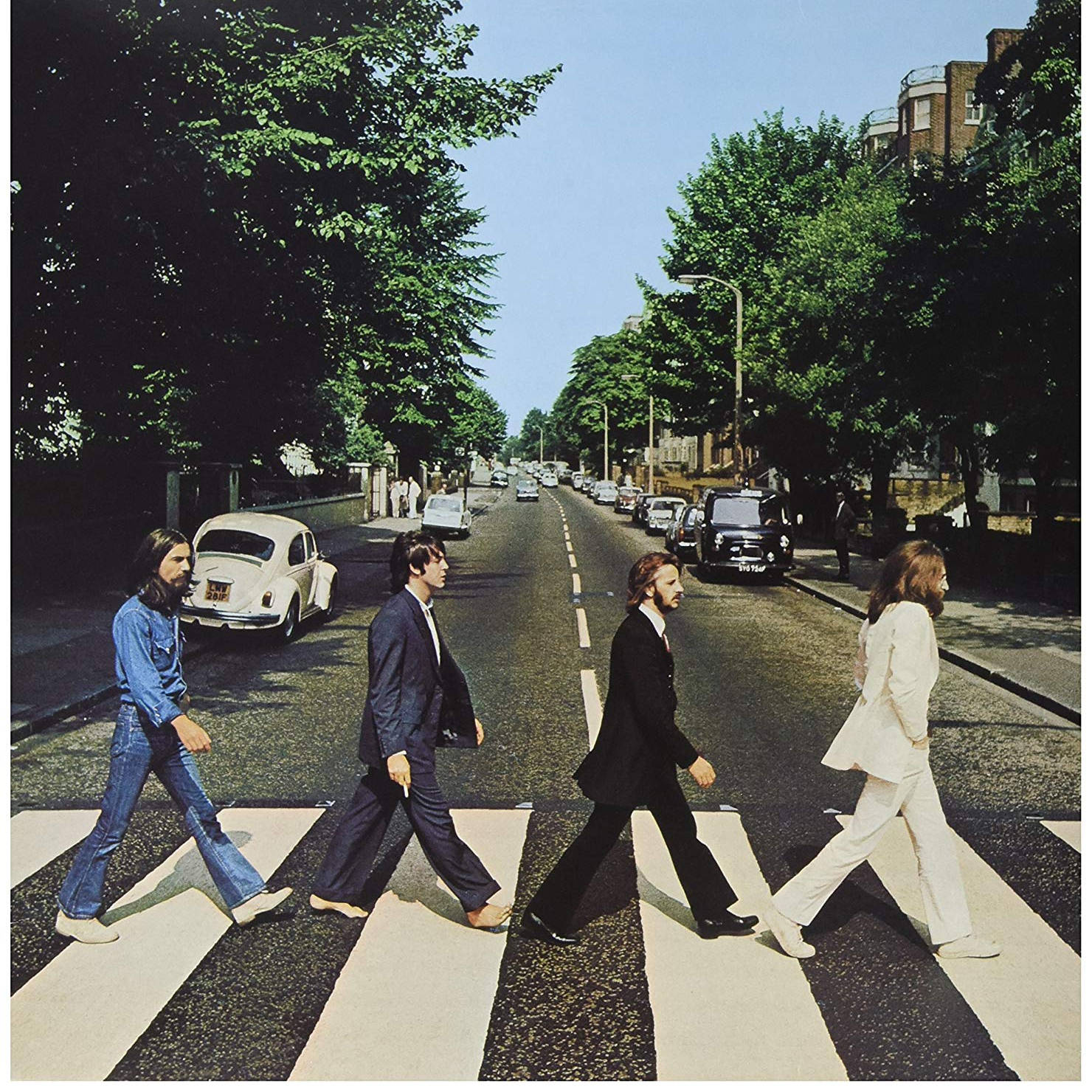

That Rattling Wine Bottle: The Best Mistake in Abbey Road History

Let’s talk about the ending. If you listen to the very last few seconds of Long Long Long, you hear this eerie, rattling vibration followed by George screaming—or more like wailing—and Ringo hitting a dramatic drum roll.

For years, fans thought this was some high-level avant-garde production trick. It wasn't.

What actually happened was a bottle of Blue Nun white wine was sitting on top of a Leslie speaker cabinet. For those who aren't gear nerds, a Leslie speaker has a rotating drum inside to create a swirling sound. When Paul McCartney hit a specific low note on the organ (a bottom C), the frequency caused the wine bottle to start vibrating against the wood of the cabinet.

Most producers would have stopped the take. They would have moved the bottle. But the Beatles by 1968 were bored with perfection. They loved the ghost-in-the-machine vibe. They kept it. George started wailing along with the rattle, and Ringo, being the intuitive genius he is, built a crescendo around it. It turned a quiet folk song into a haunting, psychedelic experience.

Ringo Starr’s Secret Weapon Status

We need to give Ringo his flowers here. Seriously.

✨ Don't miss: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

If you listen to the drums on this track, they aren't keeping time in the traditional sense. They are punctuation. The song is mostly silence and whispered vocals, and then Ringo explodes with these heavy, tom-heavy fills that sound like thunderclaps in a small room. It’s some of his best work. It shows that he wasn't just a "metronome"; he was a colorist. He played the mood, not just the beat.

The Production Ghost of Chris Thomas

George Martin, the legendary "Fifth Beatle" producer, actually wasn't there for a lot of this. He took a holiday during the White Album sessions because the band was being so difficult and argumentative. He left his young assistant, Chris Thomas, in charge.

Thomas is the one playing the piano on this track. It’s a very sparse, delicate piano part. Because John Lennon wasn't in the studio for this session (he was likely elsewhere in the building or just not interested that day), it was just George, Paul, and Ringo. This lack of "too many cooks" gave the song its breathing room. It sounds intimate because the room was literally emptier than usual.

Decoding the Lyrics: Lost and Found

George’s lyrics in the late 60s started moving away from the clever wordplay of "Taxman" into something much more direct.

- "It's been a long, long, long time"

- "How could I ever have lost you?"

- "Now I'm so happy I found you"

It’s repetitive. It’s simple. Some critics at the time thought it was "slight" or "underwritten." They missed the point. When you’re talking about a spiritual homecoming, you don’t need a thesaurus. You need a feeling. The way his voice cracks on the word "found" tells the whole story.

Interestingly, the title itself is a bit of a trick. The word "Long" is repeated three times, but in the lyrics, it’s often just twice. It feels like a reflection of the three years George spent feeling "lost" after the peak of Beatlemania in 1966.

🔗 Read more: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

How to Truly Experience the Song Today

If you’re listening to this on crappy laptop speakers, you’re missing 90% of the song. This is a "headphone song."

In 2018, Giles Martin (George Martin’s son) did a massive remix of the White Album for its 50th anniversary. If you want to hear Long Long Long the way it was meant to be heard, find that 2018 stereo mix.

The original 1968 vinyl mix was notoriously quiet—so quiet that people used to turn their volume up to hear George’s whisper, only to have their speakers blown out when the next track, "Revolution 9," started with a loud "Number nine, number nine." The remix fixes the clarity without killing the atmosphere. You can hear the wooden resonance of the acoustic guitar and the actual "burr" of the organ.

The Legacy of the "Quiet Beatle"

This song set the stage for All Things Must Pass. Without the experimentation of this track, we might not have gotten "My Sweet Lord" or "Isn't It a Pity." It was George proving to himself that he didn't need to compete with the "Lennon-McCartney" hit machine. He could just be George.

It’s a masterclass in dynamics. In a world where modern music is often "compressed" to be as loud as possible all the time, this song is a reminder that the most powerful thing you can do is lower your voice.

Actionable Takeaways for the Modern Listener

If you want to dive deeper into this specific era of music or apply the lessons of this song to your own creative life, here is how to do it:

- Listen for the "Accidents": Next time you’re recording or creating something, don't immediately delete the mistakes. The wine bottle rattle on this track is what people remember most. Sometimes the "glitch" is the art.

- Study the 3/4 Time Signature: If you’re a musician, try writing in a waltz feel. It forces you out of the standard pop grooves and lends a "timeless" or "folk" quality to your work, just like it did for George.

- Context Matters: Listen to "Helter Skelter" at full volume, then immediately play Long Long Long. The contrast is intentional. It’s meant to represent the transition from the physical, chaotic world to the internal, spiritual one.

- Check the Gear: If you're a producer, look into the "Leslie Speaker" effect on vocals and organs. It’s that watery, shimmering sound that defines the late-Beatles era.

The song might be over 50 years old, but its influence is all over modern "indie folk" and "slowcore." Bands like Low or even Radiohead owe a massive debt to the way this track uses empty space. George Harrison knew that sometimes, the longest journey is the one that leads you right back to where you started.

Next time you put on the White Album, don't skip track 14 on the second disc. Sit in the dark, turn it up, and wait for the bottle to rattle. It’s as close to a religious experience as rock music gets.