He was short. He was loud. He walked like he owned the entire city of New York, even when he was just strutting across his own living room. If you grew up in the 70s or 80s, George from The Jeffersons wasn't just a sitcom character; he was a cultural earthquake.

Sherman Hemsley brought George Jefferson to life in a way that defied every single trope of the "Black neighbor" seen on television up to that point. Before George, Black men on screen were often portrayed as sidekicks, servants, or saintly figures who never raised their voices. George changed the game. He was wealthy, unapologetic, and frankly, he could be a real jerk sometimes. But that’s exactly why he worked.

The Jeffersons originally spun off from All in the Family, where George was essentially the Black mirror image of Archie Bunker. He was the only person who could go toe-to-toe with Archie's bigotry using his own brand of stubborn pride. When the show moved him to that "deluxe apartment in the sky," it wasn't just a catchy theme song lyric. It was a statement about the Black middle class and the American Dream that hadn't been explored with that kind of raw, comedic energy before.

The Business of Being George Jefferson

Let’s talk about the dry cleaning. George wasn’t just "rich." He was a self-made entrepreneur. In an era where Black economic mobility was rarely the focal point of a primetime show, George’s seven dry-cleaning locations—Jefferson Cleaners—were a badge of honor. He worked for it. He started with one store in Queens and hustled his way to the Upper East Side.

He was obsessed with status. You see it in the way he treated his maid, Florence Johnston, played with legendary wit by Marla Gibbs. Their banter wasn't just about chores; it was a class war played out in a high-rise. George wanted to be seen as the "man of the house," the big boss, the elite. Florence, however, was there to remind him exactly where he came from. She never let him get away with his ego trips.

This dynamic served a deeper purpose. It showed a Black man who was allowed to have the same flaws as a white corporate executive. He was greedy. He was arrogant. He was competitive. Honestly, seeing a Black character allowed to be "unlikable" yet remain the hero of the story was radical. Most shows at the time felt the need to make Black characters perfect to "represent" the race well. George didn’t care about representing anyone but George Jefferson.

Why the "Strut" Mattered

If you close your eyes and think of George from The Jeffersons, you probably see the walk. It’s that rhythmic, shoulder-rolling, high-stepping gait. Sherman Hemsley actually based that walk on a dance move he’d seen as a kid in Philadelphia. It became a symbol of defiance.

It said, "I belong here."

✨ Don't miss: Who was the voice of Yoda? The real story behind the Jedi Master

Think about the context of the mid-70s. The Civil Rights movement was in the rearview mirror, but the systemic barriers were still very much there. When George walked into a room of white socialites and acted like he was better than them, it was cathartic for the audience. He wasn't asking for a seat at the table. He was buying the table and then complaining that the wood wasn't polished enough.

The Interracial Conflict with the Willises

One of the most significant parts of the show was George’s relationship with Tom and Helen Willis. They were the Jeffersons' neighbors and an interracial couple—a massive taboo for TV at the time. George hated them. Well, he claimed to. He called Tom "zebra" and constantly mocked their marriage.

But here’s the nuance: George’s prejudice wasn't the same as Archie Bunker’s. George’s anger came from a place of protecting his identity. He viewed Tom as someone who had "sold out" or compromised. Over the course of 11 seasons, we saw that wall slowly crumble. The friendship between George and Tom Willis became one of the most complex male bonds on television. They fought, they insulted each other, but when things got real, they were there.

Norman Lear, the creator, knew exactly what he was doing. He used George’s loud-mouthed bigotry to expose the absurdity of all prejudice. By making George the one who had to learn a lesson about acceptance, the show flipped the script on the traditional "lesson-learned" sitcom format.

The Reality Behind the Sitcom Laughs

It wasn’t all slapstick and "Wheezy!" screams. The show tackled some incredibly heavy topics. There were episodes about the KKK, suicide, and systemic racism. In one famous episode, George has to deal with a childhood friend who transitioned and was now a woman. In 1977! The show didn't always get the terminology right by today's standards, but the fact that George—the most traditional, stubborn guy on TV—had to navigate that reality was groundbreaking.

Then there was the episode where George is invited to join an exclusive club, only to realize they only wanted him as a "token." The pain on Hemsley’s face in those moments was a sharp contrast to his usual bombastic energy. It reminded everyone that despite the penthouse and the money, George was still living in a world that tried to shrink him.

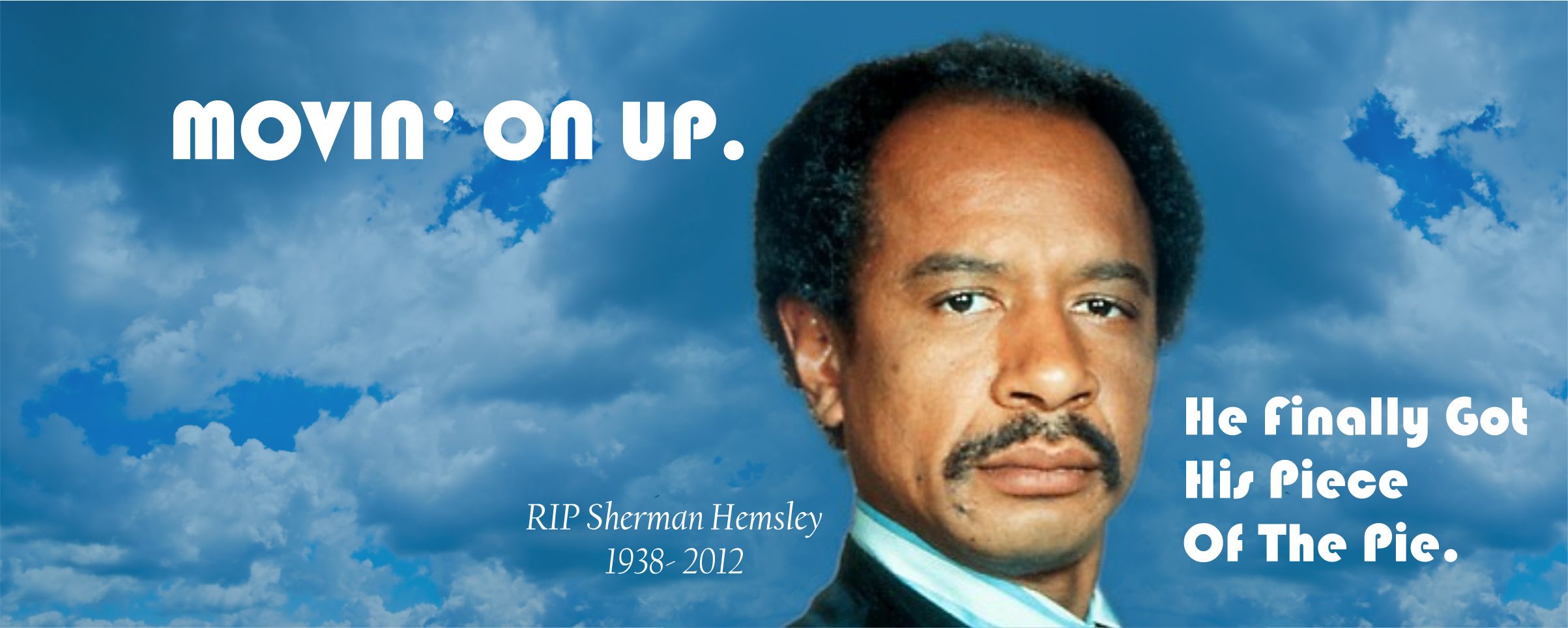

Sherman Hemsley: The Man Behind the Man

Interestingly, Sherman Hemsley was nothing like George. In real life, Hemsley was incredibly shy, a bit of a loner, and a massive fan of progressive rock (he even tried to collaborate with the band Gong). He was a jazz enthusiast who preferred a quiet life.

🔗 Read more: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

The transformation he underwent to become George from The Jeffersons is one of the great feats of American acting. He had to dial up his energy to a ten and stay there for a decade. He understood that George needed to be a "little big man." Because he was small in stature, his personality had to be gargantuan.

His chemistry with Isabel Sanford (Louise "Wheezy" Jefferson) was the heartbeat of the show. Isabel was actually several years older than Sherman, and in the early days of All in the Family, they were worried the age gap would show. It didn't. They felt like a couple that had survived the trenches of poverty together and were finally breathing the rarified air of success.

The Enduring Legacy of the 135th Floor

Why does George Jefferson still matter in 2026?

Because we are still talking about the same things: Black excellence, the pressures of the "nouveau riche," and how to stay true to your roots while moving up the social ladder. George was the blueprint for characters like Carlton Banks or even some of the personalities on Black-ish. He was the first to show that being successful and being Black wasn't a monolith.

He was a capitalist. He was a husband. He was a bit of a bigot who learned to grow. He was human.

The show ran for 11 seasons, from 1975 to 1985. It ended abruptly without a proper series finale, which was a huge slap in the face to the cast and the fans. Sherman Hemsley reportedly found out about the cancellation through the newspapers. It was a cold end for a show that had warmed so many hearts and broken so many barriers.

Actionable Takeaways for Fans and Creators

If you’re looking to revisit the impact of George Jefferson or if you’re a storyteller trying to capture that same lightning in a bottle, here’s how to look at it:

💡 You might also like: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

- Study the "Conflict of Character": George worked because he was a contradiction. He was a rich man who felt like an underdog. He was a loving husband who was often rude to his wife. When writing or analyzing characters, find that core contradiction. It’s where the humanity lives.

- Contextualize Success: Don't just look at George's wealth; look at how he got it. The "hustle" was part of his identity. In modern terms, George was the ultimate "brand builder" before that was even a phrase.

- Watch the Performance, Not Just the Lines: If you’re an actor or student of media, watch Hemsley’s physicality. He uses his entire body to communicate George’s status. Even when he’s sitting down, he’s "moving."

- Acknowledge the Evolution: George Jefferson in Season 1 is not the same man in Season 11. He became more empathetic, even if he hid it under a layer of grouchiness. Growth is essential for a long-running character to stay relevant.

George from The Jeffersons taught us that you can "move on up" without leaving your backbone behind. He was loud, he was proud, and he was undeniably one of a kind. Whether he was fighting with Florence, dancing with Wheezy, or insulting Tom Willis, George Jefferson was always 100% himself. That’s a legacy that doesn't need a penthouse to be impressive.

To truly understand the impact of the show, look at the Nielsen ratings from the late 70s. The Jeffersons consistently outperformed shows with much larger budgets and more "traditional" casts. It proved that audiences—regardless of race—were hungry for stories about the messy, complicated, and hilarious reality of the American Dream.

Next time you hear that gospel-infused piano intro, don't just hum along. Think about the man in the three-piece suit who refused to be small, even in a world designed to keep him that way. George Jefferson wasn't just a character; he was a revolution in a pinstripe suit.

Deep Dive Resources

If you want to go deeper into the history of the show, I highly recommend checking out the archives at the Television Academy Foundation. They have extensive interviews with Norman Lear and the writing staff that explain how they pushed George's character past the censors of the 1970s. You can also find scholarly articles on the "Black Sitcom Era" through the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, which often references George as a pivotal figure in television sociology.

The best way to experience George's impact is to watch the "The Draft Dodger" episode from All in the Family followed by the pilot of The Jeffersons. Seeing the transition from a supporting character to a lead provides a masterclass in character development and the shifting landscape of American media.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

- Watch "The Draft Dodger" (All in the Family, Season 7): This is the bridge episode that highlights George's moral complexity before he got his own show.

- Analyze the Florence/George dynamic: Pay attention to how the power balance shifts depending on who has the better "comeback"—it's a lesson in status-play acting.

- Explore the "Norman Lear" effect: Research how Lear used George Jefferson to pilot other social-commentary shows, changing the face of the sitcom forever.