He died because he didn't want to go to the doctor. It's a blunt, tragic way to end a life that was just reaching its peak. In 1925, George Bellows—the man who captured the sweat, blood, and grime of New York City better than almost anyone—ignored a ruptured appendix until it was too late. He was only 42. It’s one of those "what if" moments in art history that actually matters. If he’d lived, the trajectory of American realism might have looked totally different.

Most people recognize a George Bellows American artist piece without knowing his name. They see the gritty, dark-lit boxing matches or the chaotic scenes of kids diving into the East River and think, Yeah, that’s old New York. But there's a lot more to him than just sports and street urchins. He was a guy who turned down a professional baseball contract with the Cincinnati Reds just so he could paint. He chose the brush over the bat, and honestly, the art world got the better end of that deal.

The Ashcan School and the Beauty of "Ugliness"

Bellows wasn't some refined socialite painting tea parties. He was a student of Robert Henri, the leader of what critics snidely called the Ashcan School. The name was meant as an insult. It suggested they were painting trash. Bellows leaned into it. While the academic elite were obsessed with European-style landscapes and soft-focus portraits, Bellows was out in the streets of the Lower East Side.

He saw beauty in things people usually looked away from. Steam shovels digging the foundation for Pennsylvania Station. Poverty-stricken immigrants crowded onto tenements. The sheer, terrifying energy of a city growing too fast for its own good.

What makes Bellows stand out from his peers like John Sloan or William Glackens is the physical weight of his paint. You can almost feel the humidity in his landscapes. He didn't just observe New York; he wrestled with it on the canvas. His work doesn't feel like a polite invitation to look at a scene—it feels like a shove.

Stag at Sharkey’s: More Than Just a Fight

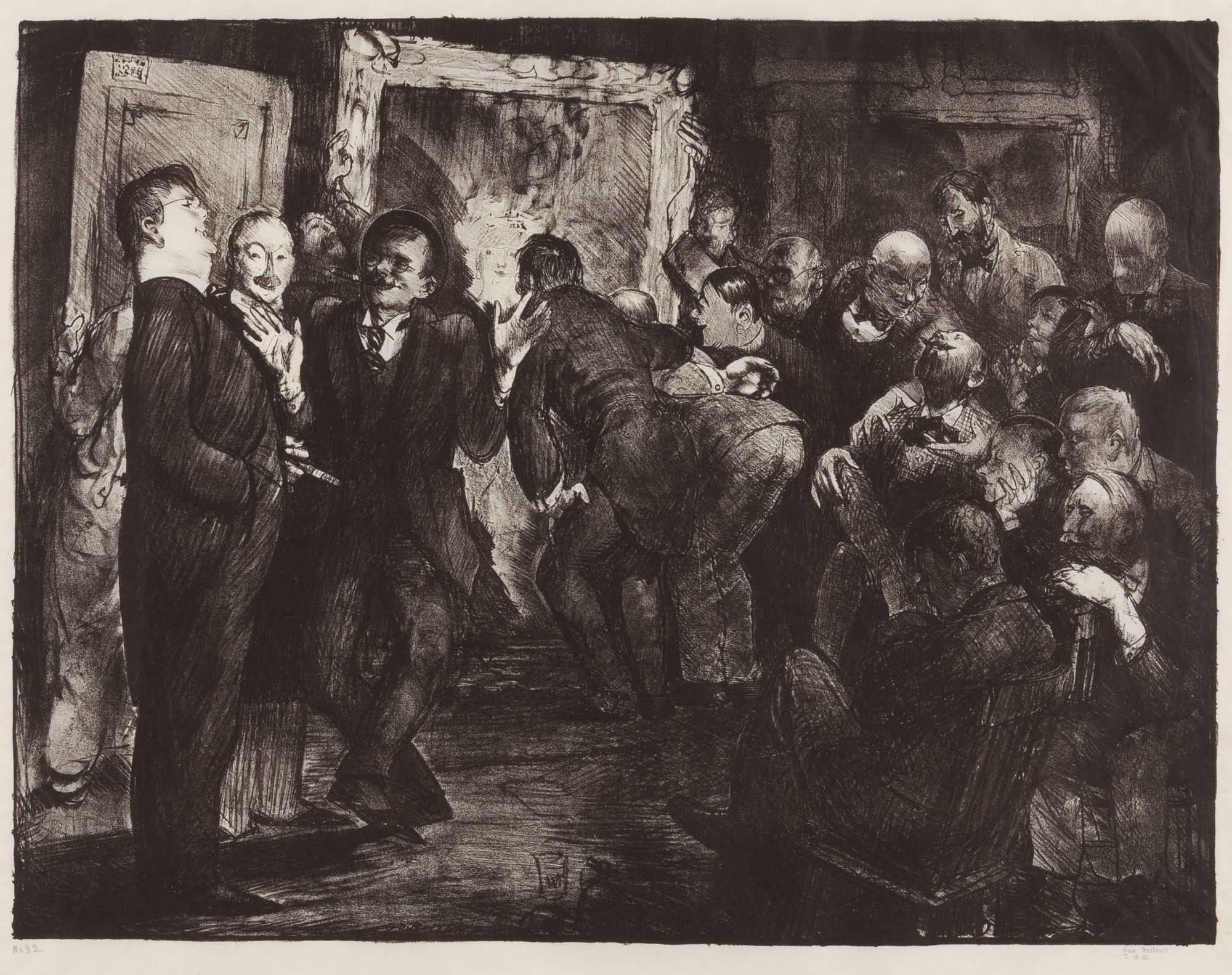

If you’ve stepped foot in the Cleveland Museum of Art, you’ve probably seen Stag at Sharkey’s. It’s arguably his most famous work. At the time, public boxing was actually illegal in New York. To get around the law, places like Sharkey’s Athletic Club operated as private "members-only" events. You paid your dues, became a "stag" for the night, and watched two men beat each other senseless in a basement.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

Bellows lived right across the street from Sharkey’s.

In the painting, the boxers aren't heroic Greek statues. They are jagged, blurry shapes. Their faces are indistinct, almost primal. The crowd in the background is even worse—a sea of distorted, bloodthirsty faces lurking in the shadows. Bellows wasn't painting a sport; he was painting the raw, ugly tension of the human condition. It’s violent. It’s dark. It’s messy.

The Myth of the "Manly" Painter

There’s this weird narrative that Bellows was just this "macho" guy because he painted boxing and played ball. It’s a bit of a caricature. If you look at his lithographs and later portraits, you see a much more sensitive, almost anxious side of the man.

He was deeply influenced by the "Big Idea" of art—the notion that art should have a social conscience. He contributed illustrations to The Masses, a socialist journal. He wasn't just some guy with a sketchbook; he was engaged with the political upheaval of the early 20th century. When World War I broke out, his work took a turn toward the horrific. His "War Series" lithographs, depicting German atrocities in Belgium, are still difficult to look at. They are brutal. Some critics at the time thought they were too much, bordering on propaganda, but Bellows felt he couldn't look away.

Modernism and the Armory Show

In 1913, the Armory Show changed everything. It brought European modernism—Cubism, Fauvism, the weird stuff—to America. Bellows helped organize it. Even though he never traveled to Europe (a rarity for major artists of his time), he was fascinated by these new ideas.

💡 You might also like: Is there actually a legal age to stay home alone? What parents need to know

He started experimenting with color theory and more rigid, geometric compositions. You can see this shift in his later landscapes of Monhegan Island in Maine. The colors get brighter, almost acidic. The brushstrokes become more deliberate. He was trying to figure out how to be "modern" without losing his realist roots.

Some people think he lost his edge in these later years. I disagree. I think he was just getting started. He was moving away from the "brown and gray" palette of the Ashcan years and finding a way to make realism feel vibrant and structural.

Why We Still Care About George Bellows

So, why does a George Bellows American artist search still trend? Why does he matter in 2026?

It’s because he captured the "American Spirit" before it became a polished marketing slogan. His work is unvarnished. It’s about the hustle, the struggle, and the weird, kinetic energy of a democracy in flux. He didn't paint the elite; he painted the people who built the buildings and fought in the basements.

There's also his technical mastery of lithography. Bellows is credited with almost single-handedly reviving lithography as a fine art form in the United States. Before him, it was mostly used for commercial posters and advertisements. He saw the potential for deep blacks and rich textures that you just couldn't get with an oil painting. If you ever get the chance to see his prints in person, take it. The depth of the ink is incredible.

📖 Related: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

Key Works to Know

If you're looking to understand the breadth of his career, don't just stick to the boxing. Look at these:

- Forty-Two Kids (1907): A bunch of skinny, pale boys swimming in the polluted East River. It was controversial at the time for being "vulgar," but it’s a perfect snapshot of urban childhood.

- Cliff Dwellers (1913): A massive, teeming street scene that captures the sheer density of New York tenement life. It’s claustrophobic and brilliant.

- Blue Morning (1909): A painting of the Pennsylvania Station excavation. It shows the transition from the old world to the new, filled with blue-collar workers and rising steel.

- Both Members of This Club (1909): Another boxing masterpiece, but this one carries heavy racial undertones, featuring a Black boxer and a white boxer, reflecting the racial tensions of the Jack Johnson era.

Where to Find Bellows Today

You don't have to go far to find his work. Most major American museums have at least one Bellows.

- The National Gallery of Art (DC): They have a massive collection of his paintings and prints.

- The Whitney Museum of American Art (NYC): Deeply invested in his role in the development of American modernism.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art (NYC): Home to some of his most iconic New York street scenes.

- Columbus Museum of Art (Ohio): Since he was a Columbus native, they have a dedicated "Bellows Center" with an incredible archive.

Actionable Insights for Art Lovers

If you're looking to dive deeper into the world of George Bellows or start a collection of American Realism, here’s how to actually do it:

- Study the Prints First: Since Bellows was a master of lithography, his prints are often more accessible for study (and sometimes purchase) than his massive oil paintings. Look for his use of "chiaroscuro"—the dramatic contrast between light and dark.

- Visit the "Ashcan" Sites: If you’re in New York, walk the Lower East Side. Much of the architecture Bellows painted is gone, but the "vibe" of the narrow streets and the proximity to the river still remains. It helps you understand his perspective.

- Read the Primary Sources: Look for the book George Bellows: Painter of America by Charles Hill Morgan. It’s one of the most comprehensive biographies out there and uses actual letters and contemporary accounts to paint a picture of the man.

- Compare Him to Hopper: To really "get" Bellows, look at a Bellows painting next to an Edward Hopper. Bellows is about the crowd and the noise; Hopper is about the individual and the silence. They are two sides of the same American coin.

George Bellows wasn't a "polite" artist. He didn't want you to just look at his work and say, "That's nice." He wanted you to feel the grit under your fingernails and the roar of the crowd in your ears. Even a century after his death, he’s still landing punches.

Next Steps for the Reader:

Check the digital archives of the National Gallery of Art to view high-resolution scans of his lithographs. Pay close attention to his 1916-1924 prints; they show a technical evolution that many people miss by only focusing on his early paintings. If you are near Ohio, plan a trip to the Columbus Museum of Art to see his personal papers and sketches, which offer a much more intimate look at his creative process than his finished gallery pieces.