It sounds like a match made in a very specific, gore-drenched heaven. You take the man who literally invented the modern zombie, George A. Romero, and you hand him the keys to the biggest survival horror franchise on the planet. In the late 1990s, this actually almost happened. Sony and Capcom were looking to bring Resident Evil to the big screen, and who better to direct it than the guy who made Night of the Living Dead?

But it didn't happen. Instead of a Romero-helmed masterpiece, we got the Paul W.S. Anderson version in 2002. Love it or hate it, that movie launched a billion-dollar franchise that drifted further and further away from horror into high-octane action. Fans have spent decades wondering about the "what if." Why did Capcom pass on a script from a legend? Honestly, the answer is a messy mix of corporate cold feet, creative clashing, and a script that was, arguably, a bit too faithful for its own good.

The Sony Commercial That Started Everything

Before there was a script, there was a commercial. In 1998, to promote the Japanese release of Resident Evil 2 (Biohazard 2), Capcom hired Romero to direct a live-action trailer. It was a 30-second blast of pure adrenaline featuring Adrienne Frantz as Claire Redfield and Brad Renfro as Leon S. Kennedy. It looked incredible. It felt like the game come to life.

Capcom executives were reportedly so impressed by the production value and Romero's efficiency that they tapped him to write and direct the feature film. At the time, Romero was struggling. He hadn't directed a major feature since 1993’s The Dark Half. He saw this as his big comeback. He played the game—or rather, he watched his assistant play it—to soak in the atmosphere of the Spencer Mansion. He wanted to get it right.

What was actually in the Romero script?

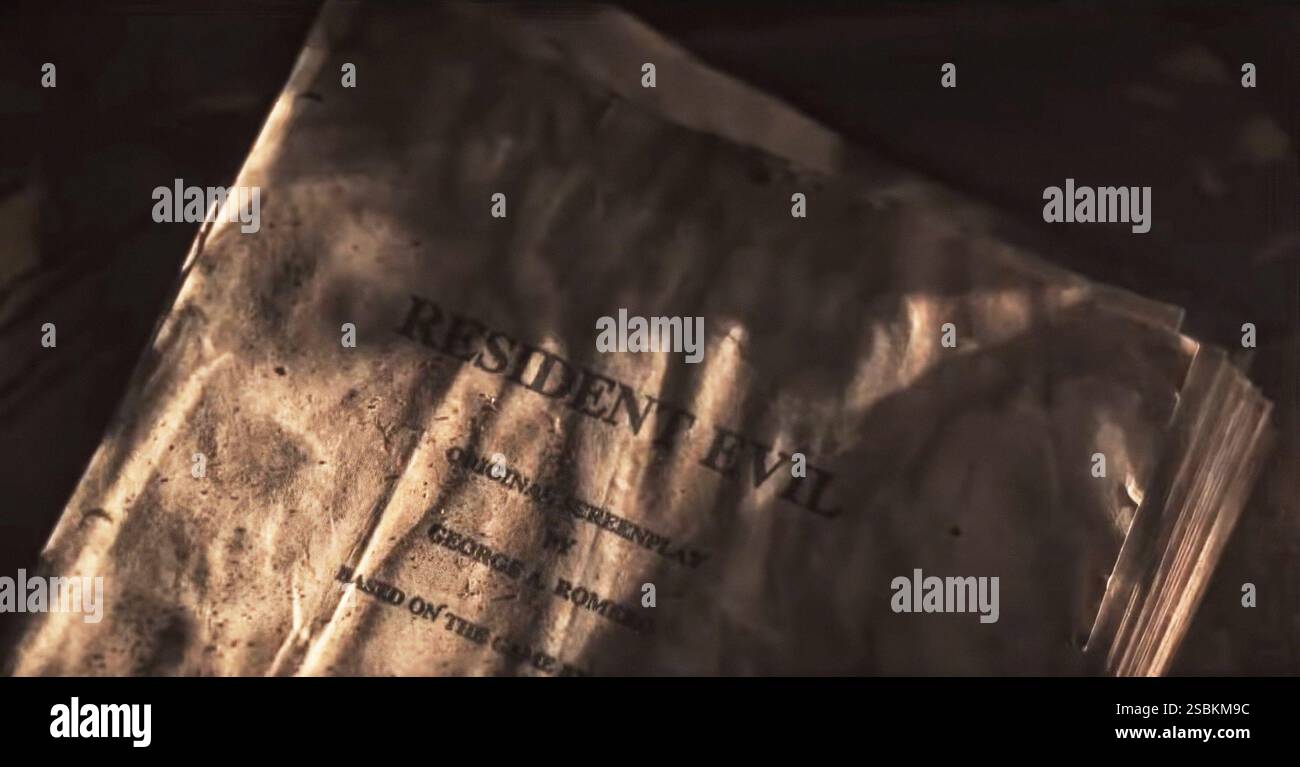

If you go looking online, you can find drafts of the George A. Romero Resident Evil script. It’s a fascinating read because it feels like a time capsule. Unlike the 2002 movie, which introduced Alice (a character who didn't exist in the games), Romero’s script stuck to the source material. Mostly.

✨ Don't miss: Elaine Cassidy Movies and TV Shows: Why This Irish Icon Is Still Everywhere

The story followed Chris Redfield and Jill Valentine. It featured the mansion, the lab, and the STARS team. But Romero made some "kinda" weird choices that might have ruffled feathers at Capcom. For starters, Chris Redfield wasn't a STARS member; he was a local farm boy with Mohawk heritage who lived near Raccoon City. Jill was still the tactical expert, and their romance was the heart of the movie.

Romero’s vision was R-rated. Very R-rated. He wanted the gore to be tactile and practical. He wanted the "Yawn" (the giant snake), the "Plant 42," and the "Tyrant." He even included a scene where a shark—the Neptune—gets blasted. It was essentially a beat-for-beat adaptation of the first game’s plot, filtered through the lens of 70s grit. It wasn't "slick." It was dirty and claustrophobic.

Why Capcom Hated It

There’s a famous quote from Capcom producer Yoshiki Okamoto, who said the script was just "bad." That’s a harsh word for a master of horror. But if you look at it from a corporate perspective, you start to see the friction.

Romero was a rebel. He hated the "studio system." Capcom, on the other hand, was an emerging global brand that wanted to protect its intellectual property. They didn't want a "Romero movie"; they wanted a "Resident Evil movie" that appealed to everyone. Romero’s script was bleak. It had that signature Romero nihilism where authority figures are incompetent and the world is basically doomed.

🔗 Read more: Ebonie Smith Movies and TV Shows: The Child Star Who Actually Made It Out Okay

Also, the changes to Chris Redfield were a major sticking point. Why change the protagonist’s entire backstory? For a fan-base that was already obsessed with the lore, making Chris a civilian felt like an unnecessary deviation. While Romero was trying to make the characters more "relatable" to a general audience, he was inadvertently alienating the hardcore gamers who were supposed to be the core demographic.

The budget was another factor. Romero’s script was ambitious. It required massive sets and complex animatronics. In the late 90s, CGI was still expensive and often looked terrible (look at the effects in Spawn or The Mummy). To do the Tyrant justice with practical effects would have cost a fortune. Sony wanted a sleek, Matrix-style action flick. Romero wanted a slow-burn horror movie about people trapped in a house.

The Paul W.S. Anderson Pivot

By 1999, Romero was off the project. He later said in interviews that he didn't think Capcom ever really wanted his vision. He felt they used his name for PR and then got scared when he handed in something that wasn't a "popcorn" movie.

Enter Paul W.S. Anderson. He had just come off Event Horizon and Mortal Kombat. He knew how to talk to studios. He proposed a "prequel-ish" story that functioned as its own thing. It was cheaper, it was faster, and it featured Milla Jovovich kicking dogs in mid-air. It was exactly what the early 2000s wanted.

💡 You might also like: Eazy-E: The Business Genius and Street Legend Most People Get Wrong

Was it a better movie? That depends on who you ask. If you want a scary movie, Romero’s script wins. If you want a franchise that can sell toys and sequels for twenty years, Anderson’s version was the "correct" business move. But for horror purists, the loss of the Romero version remains one of cinema's great tragedies. We missed out on seeing the Godfather of Zombies tackle the most iconic zombie game.

The Legacy of a Ghost Movie

Even though it was never filmed, the Romero script has had a weirdly long afterlife. You can see bits of its DNA in later adaptations. The 2021 film Resident Evil: Welcome to Raccoon City actually tried to do what Romero intended—merging the first two games and focusing on the original characters—but it lacked the atmospheric dread that Romero was known for.

Romero eventually went back to his own roots and made Land of the Dead in 2005. It’s a great movie, but you can see the lingering influence of his Resident Evil research in some of the more "evolved" zombie behaviors.

One thing is certain: the George A. Romero Resident Evil movie would have been unique. It wouldn't have been a superhero movie. It would have been a claustrophobic, terrifying nightmare about a corporation that didn't care who lived or died. In many ways, that’s exactly what the games were about before they became about punching boulders in volcanoes.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Collectors

If you're obsessed with this lost piece of horror history, there are a few things you can actually do to experience a "version" of it.

- Read the Script: Several versions of Romero's 1998 script are archived on fan sites like Resident Evil Database or horror script archives. Reading it while listening to the original Resident Evil 1 (1996) soundtrack is the closest you'll ever get to seeing the movie.

- Watch the RE2 Japanese Commercial: Seek out the "Biohazard 2" commercial directed by Romero on YouTube. It’s only 30 seconds, but it proves that he had the visual language of the games down perfectly.

- Track Down the Documentary: There has been a long-gestating documentary titled George A. Romero’s Resident Evil (by director Brandon Salisbury) that features interviews with the people who were in the room. Keeping an eye on film festival circuits for this is a must for any completionist.

- Comparative Play: Play through the Resident Evil 1 Remake (2002) and notice the "Lisa Trevor" subplot. This kind of tragic, grotesque body horror is exactly what Romero excelled at, and it's the element most missing from the Paul W.S. Anderson films.

The tragedy isn't just that the movie wasn't made; it's that it was cancelled because it was "too much" like the source material for the people who owned the source material. It's a classic case of Hollywood over-thinking a simple, winning formula.