You’re cruising down the highway in your Silverado, the radio is up, and everything feels fine. Then you glance at the dash. For a split second, that little "V8" icon flickers and changes to "V4." You didn't feel a thing. No lurch, no stumble. That is General Motors Active Fuel Management doing its job. It's a piece of engineering that sounds like magic on paper—turning a massive engine into a tiny one to save you money at the pump.

But if you’ve spent any time on truck forums or at a local garage, you know the name "AFM" usually comes with a heavy sigh or a string of profanities.

The system is basically a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde situation. It’s a clever solution to tightening fuel economy standards, yet it’s also the reason many GM owners find themselves staring at a $4,000 repair bill for "lifter failure" before the truck even hits 100,000 miles. Honestly, the gap between what GM promised and what owners experience is huge.

How General Motors Active Fuel Management Actually Works

Most people think the engine just stops sending spark to certain cylinders. I wish it were that simple. If you just stopped the spark, those pistons would still be pumping air, creating "pumping losses" that would eat up almost all your fuel savings.

To actually save gas, you have to stop the valves from moving entirely.

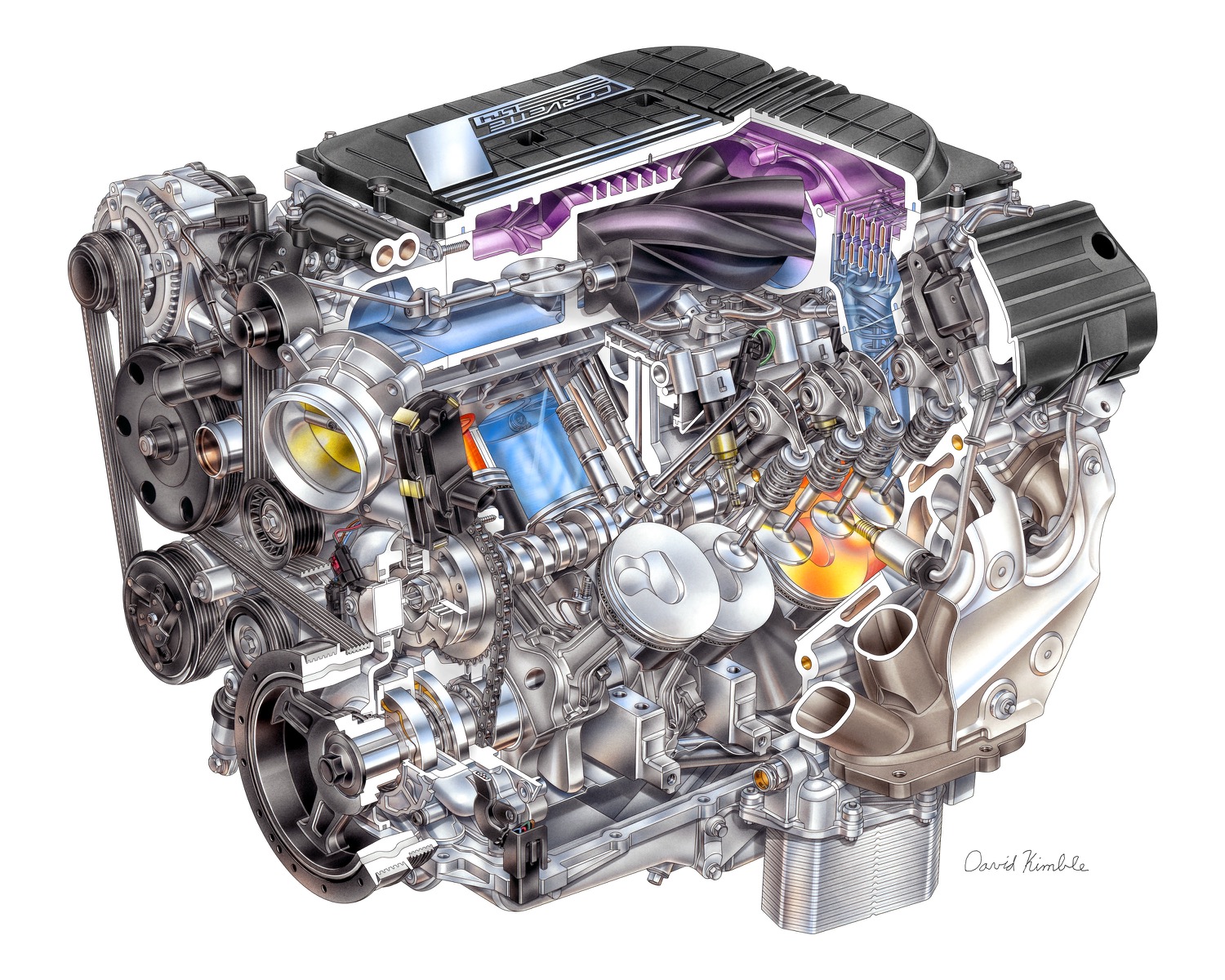

Inside an AFM-equipped engine, like the legendary 5.3L or 6.2L V8s, GM uses special "collapsible" hydraulic lifters on half of the cylinders. When the Engine Control Module (ECM) decides you’re just coasting or light on the throttle, it sends a signal to a solenoid manifold tucked under the intake. This manifold shoots high-pressure oil into those special lifters.

The oil pressure pushes a tiny locking pin inside the lifter. Once that pin moves, the lifter collapses into itself like a telescope. The camshaft keeps spinning, the bottom of the lifter keeps moving up and down, but the top part—the part that pushes the pushrod—just stays still. The valves stay closed. The cylinder becomes an air spring.

It’s a wild dance that happens in milliseconds. One second you're a 355-horsepower beast; the next, you're basically driving a 2.6L four-cylinder.

The MPG Myth: Is It Worth It?

GM claimed that General Motors Active Fuel Management could boost fuel economy by anywhere from 5% to 12%. In a lab, that looks great. In the real world? It’s complicated.

If you live in flat-as-a-pancake Nebraska and spend your life at 65 mph with the cruise control on, you might actually see those gains. But for most of us—driving in traffic, dealing with hills, or carrying a bed full of tools—the system is constantly cycling on and off.

Many owners report that the actual savings are closer to 1 or 2 mpg. When you weigh that against the potential for catastrophic engine damage, the math starts to look a little shaky. You've gotta ask yourself if saving $150 a year on gas is worth a $3,000 top-end rebuild down the road.

The "AFM Tick" and Why It Happens

This is the part where things get messy. The biggest flaw with the system is the lifters themselves. Because they rely on precise oil pressure to lock and unlock, they are incredibly sensitive.

If you're even a little lazy with oil changes, carbon and sludge start to build up. That tiny locking pin gets sticky. Sometimes it doesn't lock back into place when you step on the gas to pass a semi. That’s when you hear it: the "tick-tick-tick" of a collapsed lifter.

Once that happens, the engine starts misfiring. The check engine light starts flashing. In the worst-case scenario, the failed lifter can actually chew up the camshaft lobe. At that point, you aren't just replacing a lifter; you're tearing the whole engine down.

Common Signs Your AFM Is Giving Up

It’s rarely a sudden "bang." Usually, the system gives you some warning signs that it's unhappy.

- Vibration in V4 mode: You might feel a subtle shudder or "drone" through the steering wheel when the system deactivates cylinders.

- Oil Consumption: This is a big one. Engines with General Motors Active Fuel Management are notorious for burning oil. When the cylinders are deactivated, the oil rings can sometimes "cook" or get stuck because of the temperature changes, allowing oil to seep past.

- The Ticking Sound: If your truck sounds like a sewing machine on a cold start, pay attention. If the sound doesn't go away after the engine warms up, you likely have a lifter issue.

- Fouled Spark Plugs: Since the deactivated cylinders aren't burning fuel, they can get "wet" with oil spray, leading to fouled plugs and rough idling.

The Great Debate: Disable vs. Delete

If you own one of these vehicles and want to keep it forever, you basically have two choices to save your engine from its own fuel-saving tech.

1. The OBD-II Disabler (The "Band-Aid")

Companies like Range Technology make a little device that plugs into your truck's diagnostic port. It basically "tricks" the computer into thinking it should never leave V8 mode. It’s plug-and-play. You don’t even need a wrench.

The upside? No more V4 mode, no more weird vibrations, and the lifters stay pressurized. The downside? The "bad" hardware is still inside your engine. If a lifter was already on its way out, this might not save it. Plus, you’ll lose that tiny bit of fuel economy.

2. The Full Mechanical Delete (The "Cure")

This is the nuclear option. You literally pull the heads off the engine, throw the AFM lifters in the trash, and replace them with "standard" LS lifters. You also have to swap the camshaft and the oil pump, and then reprogram the computer so it doesn't look for the system anymore.

It’s expensive. It’s labor-intensive. But it makes the engine "dumb" again—and in the world of GM trucks, "dumb" usually means "bulletproof."

Evolution to Dynamic Fuel Management (DFM)

Around 2019, GM realized that "half-on or half-off" wasn't enough. They introduced Dynamic Fuel Management.

While AFM could only drop 4 cylinders on a V8, DFM is much more sophisticated. It can run in 17 different patterns. It can run on two cylinders, three cylinders, or even just one. It’s governed by a computer that makes calculations 80 times per second.

Is it more reliable? The jury is still out. While it's smoother, it still uses the same basic concept of oil-controlled collapsible lifters. In fact, it uses more of them. On a DFM engine, every single cylinder has the potential to deactivate, meaning you have 16 potential points of failure instead of 8.

👉 See also: Elon Musk's xAI Startup Raises Another $6bn: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Insights for Owners

If you're currently driving a GM vehicle with this tech, you aren't necessarily driving a ticking time bomb, but you do need to be proactive.

Change your oil every 3,000 to 5,000 miles. Forget what the "Oil Life Monitor" says. These systems live and die by oil cleanliness. Use a high-quality full synthetic. Keeping those tiny oil passages clear is the best defense you have.

Watch your oil level like a hawk. Since these engines are prone to consumption, running even one quart low can drop the pressure enough to cause a lifter to malfunction. Check the dipstick every other fuel fill-up.

Consider an OBD-II Disabler early. If you plan on keeping the truck past its warranty, spending $200 on a disabler is cheap insurance. It stops the constant "cycling" of the hardware, which theoretically reduces the mechanical wear and tear on those complex lifter internals.

Listen to the engine. Don't ignore a new noise. If you catch a "lazy" lifter early, you might be able to save the camshaft. Once the cam is damaged, the repair cost doubles.

General Motors Active Fuel Management was a noble attempt to keep the V8 alive in an era of strict environmental rules. It’s an impressive feat of engineering that, unfortunately, adds a layer of fragility to engines that were once known for being indestructible. Treat it with a little extra care, and it’ll likely treat you fine. Ignore the maintenance, and it might just turn your V8 into a very expensive paperweight.