You just bought a beautiful Japanese Maple. It’s perfect. You spent sixty bucks, hauled it home, dug the hole, and watered it like a devoted parent. Then January hits. A polar vortex screams down from the Arctic, and by April, your expensive tree is a brittle stick of grey wood. What happened? You probably trusted an outdated map. Honestly, gardening zones North America are shifting faster than most of us can keep up with, and if you aren't looking at the 2023 USDA update, you’re basically gambling with your backyard.

The map isn't just a suggestion. It's a survival guide.

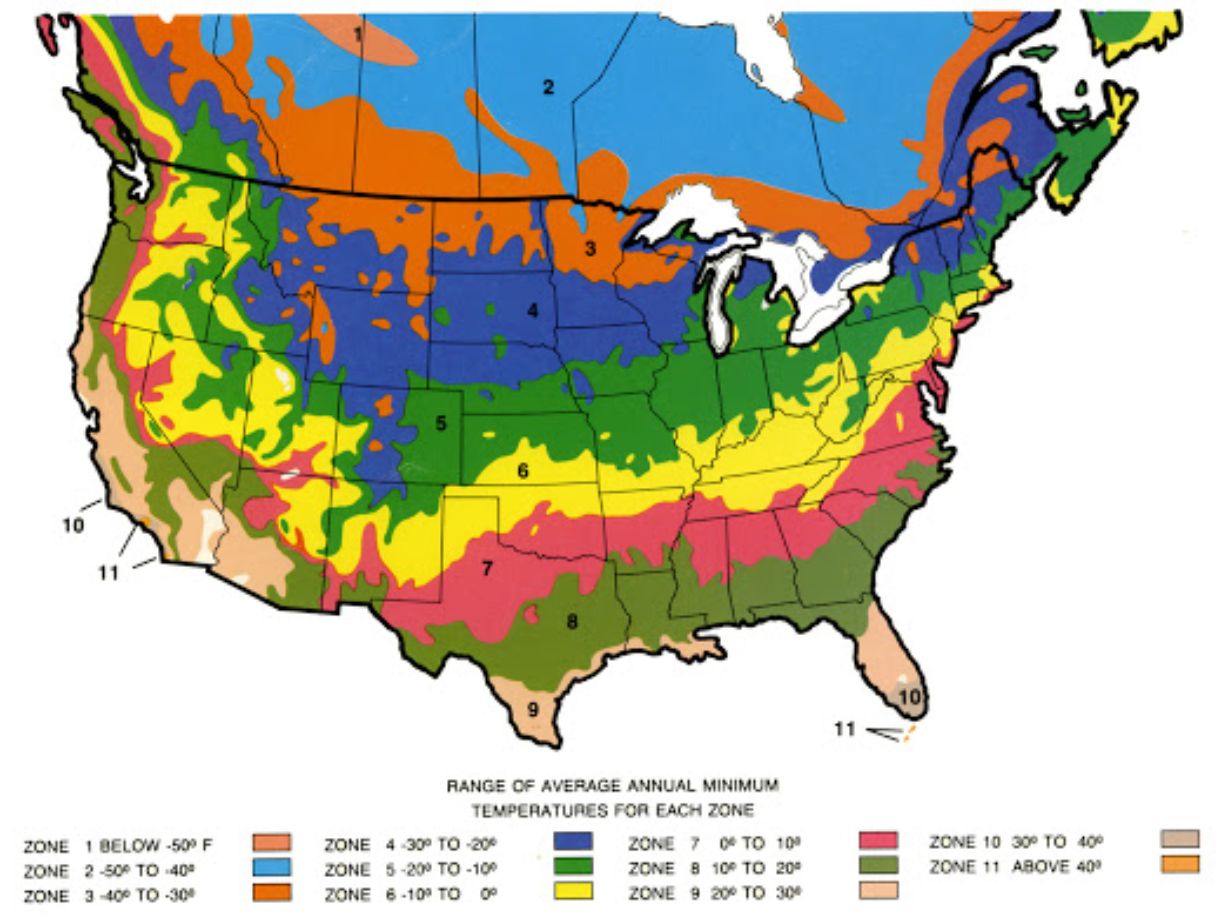

Most people think of these zones as "where plants grow." That’s wrong. These zones measure one thing and one thing only: the average annual extreme minimum winter temperature. It’s about how cold it gets before things start dying. In North America, we deal with everything from the frozen tundra of Nunavut to the tropical humidity of the Florida Keys. Trying to apply the same rules to a garden in Calgary and a garden in Charlotte is madness. But even within those regions, the lines are blurring.

The Great Shift: Why Your Zone Probably Changed

In late 2023, the USDA released its first major update to the Plant Hardiness Zone Map in over a decade. It was a massive deal. Roughly half of the United States shifted into a warmer half-zone. If you were a 6a, you might be a 6b now. If you were a 7, you might be an 8. This isn't just a theoretical change for scientists to argue about in labs. It means plants that used to perish in your winter might now survive, and plants that need a long "chill hour" period to fruit—like certain apples or cherries—might start failing because your winters are too wimpy.

Climate change is the elephant in the room. Data from over 13,000 weather stations went into this new map. We are seeing a northward creep of warmth.

Take the Midwest. Places like Des Moines or Chicago used to be synonymous with "Zone 5" logic. You planted hostas, daylilies, and maybe some tough hydrangeas. Now, gardeners in these areas are experimenting with things that used to be reserved for the mid-South. But there's a catch. Just because the average low is warmer doesn't mean the extreme lows have disappeared. We still get those freakish "Siberian Express" winds. A plant rated for Zone 7 might live through three mild winters in Zone 6, only to be wiped out in year four by a single night of -10°F.

Understanding the Math Behind the Map

The map is divided into 10-degree Fahrenheit zones. Those are then broken down into "a" and "b" half-zones of 5 degrees each.

💡 You might also like: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

- Zone 1 is the coldest, where temperatures can drop below -60°F. Think high-altitude Alaska or the deepest parts of the Canadian Shield.

- Zone 13 is the warmest, where it never drops below 60°F. You'll find this in places like Puerto Rico or very specific pockets of Hawaii.

Most of the continental U.S. and Southern Canada falls between Zones 3 and 10. The problem is that many gardeners treat the map like a "permission slip." They see "Zone 7" on a tag at the nursery and assume it’s a guarantee. It's not. It's a probability. Biology doesn't care about our colored lines on a map. A plant’s health depends on soil pH, drainage, wind exposure, and the "heat island effect" if you live in a city. Concrete soaks up heat during the day and spits it back out at night. A downtown garden in Toronto might technically function as a Zone 7 pocket while the suburbs twenty miles away are a punishing Zone 5.

Canada’s Unique Struggle with Hardiness

Gardening zones North America aren't just a USDA thing. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) has its own system, and it’s actually a bit more sophisticated—and complicated—than the American version. While the U.S. map focuses almost exclusively on winter lows, the Canadian map looks at seven different variables. They factor in frost-free days, summer rainfall, maximum temperatures, snow cover, and wind speed.

It makes sense. In the Canadian prairies, the cold isn't the only killer. It’s the desiccating wind. You can have a plant that can handle -30°F, but if it gets hit by 50mph frozen winds all January without snow cover to insulate the roots, it’s toast.

If you're gardening in British Columbia, specifically the Vancouver area, you're playing a different game entirely. You've got Zone 8 or even Zone 9 conditions. You can grow palms. Actual palm trees in Canada. But move inland toward the Rockies, and you drop four zones in a few hours of driving. This verticality is something the broad-stroke maps often struggle to show. Topography matters. A valley floor is often colder than a hillside because cold air is heavy and sinks. Gardeners call these "frost pockets." You might be in Zone 6, but if your garden is at the bottom of a hill, your peonies might get zapped by frost two weeks after your neighbor's on the ridge.

The Myth of the "Safe" Perennial

We need to talk about the "Zone Pushers." These are the rebels of the gardening world. They live in Zone 5 and try to grow Zone 7 gardenias by wrapping them in burlap and stuffing them with leaves every winter. Sometimes it works. Usually, it’s a lot of work for a mediocre result.

The real danger of the shifting gardening zones North America is the loss of dormancy. Plants need sleep. Many temperate plants require a specific number of "chill units" to reset their internal clocks. If the winter is too warm, the plant doesn't go fully dormant. It wakes up too early, the sap starts flowing, and then a normal spring frost hits. The frozen sap expands, the bark splits, and the plant dies. This "false spring" phenomenon is becoming a bigger threat to North American orchards than the deep winter cold itself.

📖 Related: Lo que nadie te dice sobre la moda verano 2025 mujer y por qué tu armario va a cambiar por completo

How to Actually Use This Information

Stop looking at the map as a static law. Look at it as a baseline.

First, go to the USDA or AAFC website and type in your zip code or postal code. Don't guess. Don't look at a map from 2012. Get the current data. Once you have your number—let's say you're in Zone 6b—don't just buy 6b plants. Buy Zone 5 plants for your "backbone." These are the trees and shrubs that must survive for your landscape to look good. If they die, your yard looks like a construction site. Save the "experimental" Zone 6 or 7 plants for containers or small flower beds where they can be replaced without breaking your heart (or your bank account).

Microclimates: The Secret Weapon

Your yard isn't one uniform temperature. The south-facing side of your brick house is likely a full zone warmer than the north-facing side under a pine tree.

- The South Wall: This is where you put your "stretch" plants. The brick holds thermal mass. It's the warmest spot you have.

- The Low Spot: Avoid putting early-bloomers here. This is where the last frost of spring will linger.

- The Windbreak: If you have a fence or a hedge, the area behind it is protected from the "wind chill" that dries out evergreens in winter.

I knew a guy in Denver (Zone 5/6) who grew semi-tropical figs against a south-facing stone wall. He’d bury the branches in mulch every November. It was insane, but he got fruit. That’s the power of understanding microclimates within your broader zone.

Water and Soil: The Overlooked Killers

People blame the cold when a plant doesn't come back in the spring, but often, it was the water. Or lack of it. In many parts of the West and Southwest, gardening zones North America are becoming less about temperature and more about aridity. If you are in Zone 9 in Phoenix, your challenge isn't the winter low; it's the summer high and the lack of moisture.

Ironically, wet soil in winter is often what kills "hardy" plants. Lavender, for instance, can handle quite a bit of cold. What it cannot handle is "wet feet" in February. If the soil is heavy clay and stays soggy, the roots rot. When the plant doesn't leaf out in May, the gardener says, "Oh, it was too cold." Nope. It drowned in its sleep.

👉 See also: Free Women Looking for Older Men: What Most People Get Wrong About Age-Gap Dating

Native Plants and the Zone Fallacy

There is a growing movement toward native gardening, and for good reason. Native plants have spent thousands of years adapting to the specific "weirdness" of your local weather. They don't just know the average cold; they remember the once-in-a-century drought and the three-week flood.

However, even "native" is becoming a tricky term. If the zones are shifting north, should we be planting species that are native to 100 miles south of us? Some ecologists call this "assisted migration." It’s controversial. Some say we should help trees move north so they don't go extinct as their current habitats heat up. Others worry about invasive behavior.

Regardless of where you stand on the ethics, the practical reality is that the "reliable" plants of our grandparents' generation might not be the reliable plants for our grandchildren. The sugar maples of New England are struggling. The loblolly pines of the South are marching north.

Actionable Steps for the Modern Gardener

Don't just stare at the map and sigh. There are things you can do right now to future-proof your garden against the volatility of North American weather patterns.

- Check your updated zone. Use the 2023 USDA map or the latest AAFC data. Do not rely on the back of a seed packet printed in 2015.

- Audit your yard's microclimates. Spend a day in winter observing where the snow melts first and where it lingers. That tells you everything about your heat distribution.

- Plant for "One Zone Colder." If you want a tree to last 50 years, make sure it can handle a winter significantly worse than your current average.

- Focus on soil drainage. Dig a hole, fill it with water, and see how long it takes to empty. If it takes more than an hour, you need to amend that soil or plant things that love "wet feet," regardless of your zone.

- Mulch like your life depends on it. A thick layer of wood chips or shredded leaves acts like a thermal blanket. It keeps the ground from freezing and thawing repeatedly, which is what "heaves" plants out of the dirt and kills them.

- Record your own data. Buy a cheap min-max thermometer. Put it in your garden. Compare your actual backyard lows to the official airport data used for the maps. You might be surprised to find you’re 5 degrees colder than the "official" zone.

The map is a tool, not a crystal ball. Gardening in North America is getting weirder, but it’s also getting more interesting. We have the chance to grow things our parents never dreamed of—as long as we're smart about the risks. Pay attention to the dirt, watch the wind, and maybe keep a burlap sack handy just in case that polar vortex decides to pay a visit.